In her day, she was considered a style icon, spendthrift, deviant, monster, and hapless victim. And why are we still talking about her and dissecting her lifestyle, look, and acquisitions over 200 years later?

You’ll find the answer in the South Kensington V&A galleries with portraits, clothes, artifacts, and haute couture fashion in Marie Antoinette Style, on view in London through March 22, 2026.

The Victoria & Albert Museum has pulled incredibly well-preserved fashions from its own 18th-century collection, and has also borrowed from Versailles and European collections that scooped up Marie’s stuff when it was ransacked and put on the open market after her death during the French Revolution – jewels, furniture, Sèvres table settings, and remnants of her dress fabric.

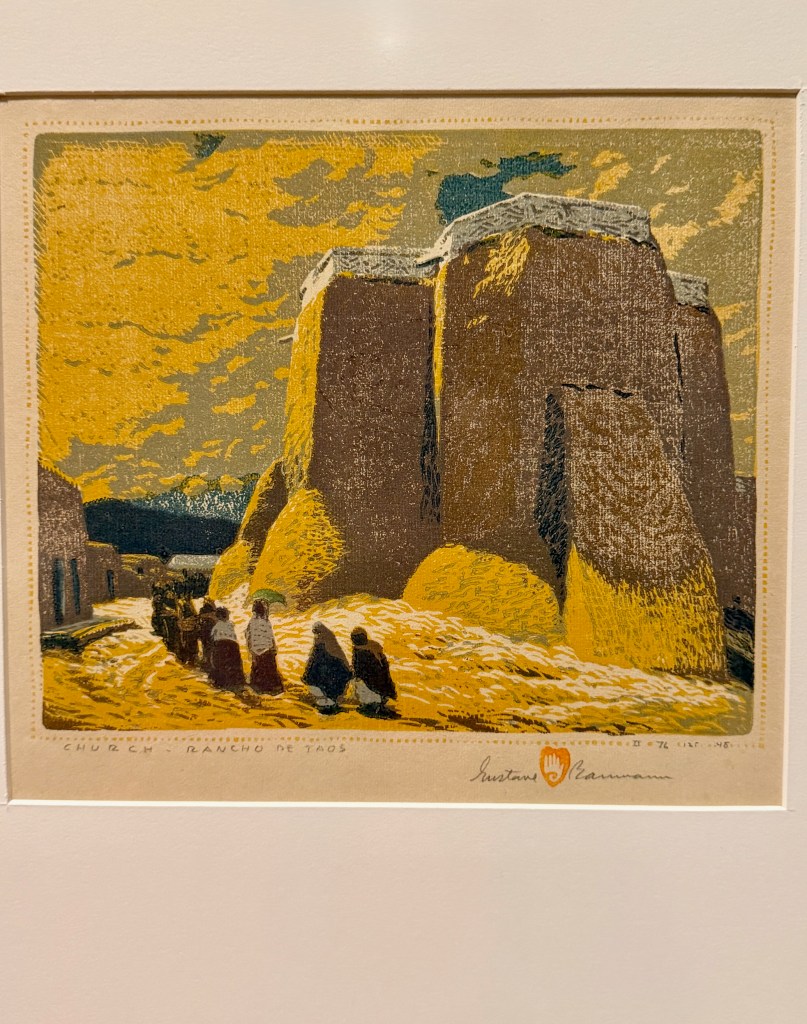

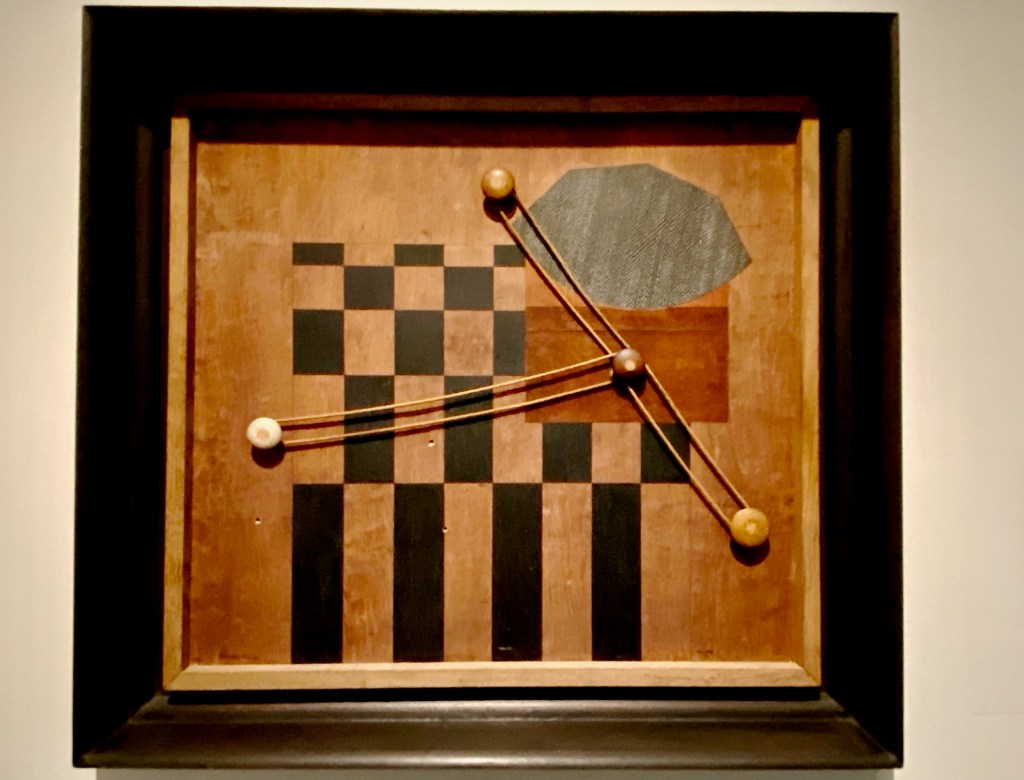

As befitting a Versailles icon, the introductory gallery is a dazzling room of mirrors. With the dramatic illumination of opulent court dresses, wedding attire, royal portraits nof Marie, fans, and swaths of over-the-top embroidered silk, the effect is magnified by the points of light dancing across multiple reflections of sumptuously draped fabric.

Take a look through some of our favorites on display in our Flickr album.

You experience how Marie’s fashion sense changed from the big-time Rococo style she sported as a teen to the more minimal muslin style she popularized as she and her friends gallivanted around the Tríanon grounds in jaunty Italian straw bonnets.

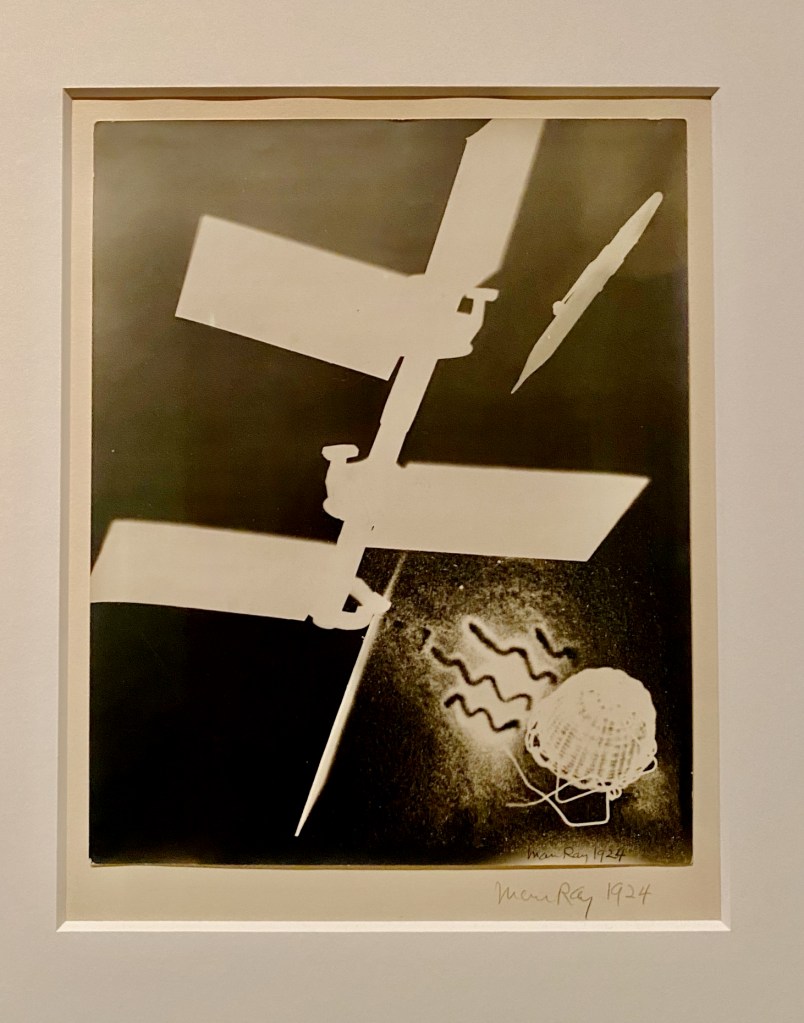

Plates from 18th-century fashion publications show off the latest extravagant details of hair poufs that Marie popularized. Incredibly, there’s also an actual shoe owned by the style icon herself. As queen, she received four new pairs of shoes per week! Watch this short video to get a close-up view of her 230-year-old silk and kid shoe that survived!

During her reign, Marie had an outsized influence on interior design, landscape architecture, the decorative arts, and music. Her fashion selections and hairstyles were noted, discussed, and copied.

When the winds of democratic change came to France, Marie’s attire changed again to a more pared-down republican look that every patriotic woman in Paris also sported, right down to the patriotic silk cockades pinned to hats and lapels.

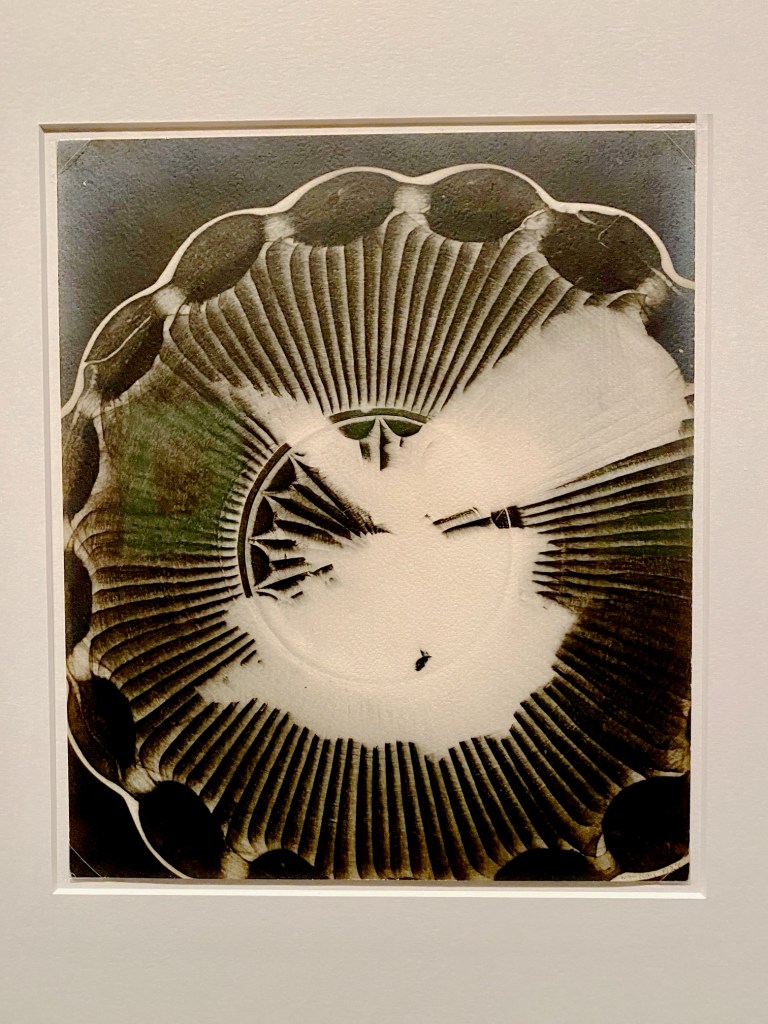

But by then public opinion had turned against Marie, largely due to the unfortunate incident that completely tarnished the public’s view of her – The Diamond Necklace Affair. In an exhibition section titled “The Queen of Sparkle,” the curators display a modern copy of the necklace that created the ruckus alongside lavish jewelry created from the diamonds removed (and resold) by an 18th-century con artist.

Here, the V&A’s Senior Curator Sarah Grant provides a close-up look at those infamous diamonds and tells the story:

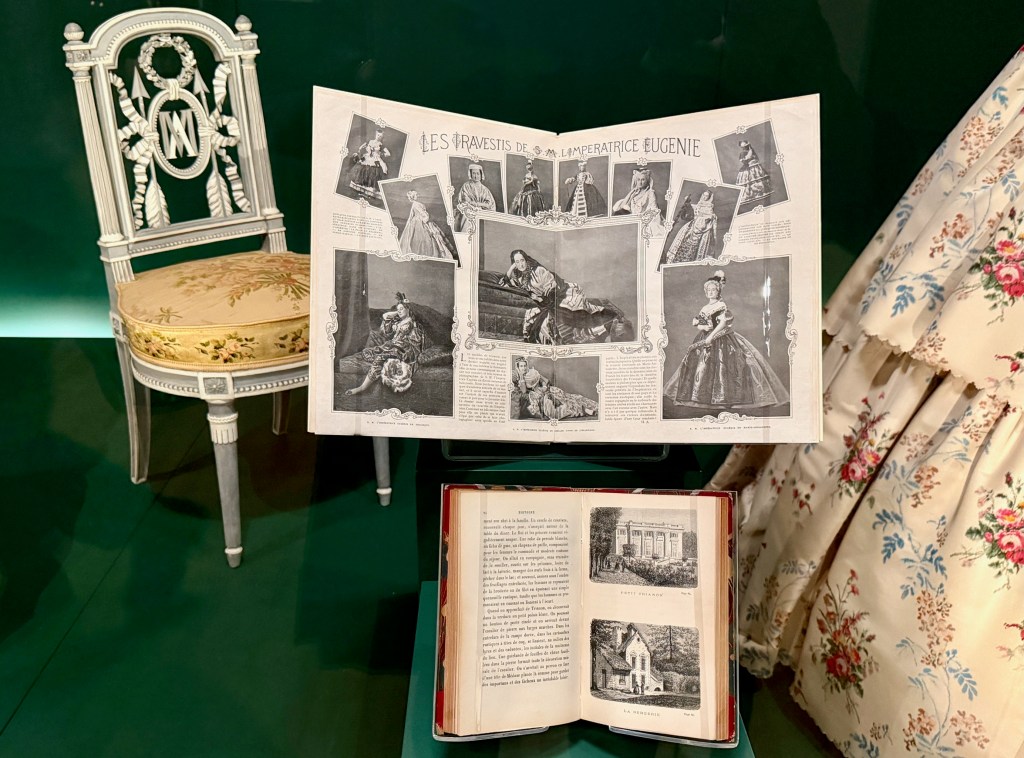

Decried, denounced, and executed, it’s remarkable that 75 years later, Marie-Antoinette style and influence had a come-back, thanks to an obsessive 19th century fan, Empress Eugénie of France. Eugénie loved Marie’s fashion sense began sporting her look at various fancy-dress balls. She even commissioned haute courtier designer Charles Frederick Worth to design some looks, and he was happy to oblige.

Over the years, the Marie Antoinette’s Tríanon retreat had fallen into extreme disrepair and its contents scattered. Eugénie set about to find much of the furniture Marie had commissioned, did a major rehab job on the property, and had a big, public exhibition about Marie at the Tríanon’s reopening in 1867.

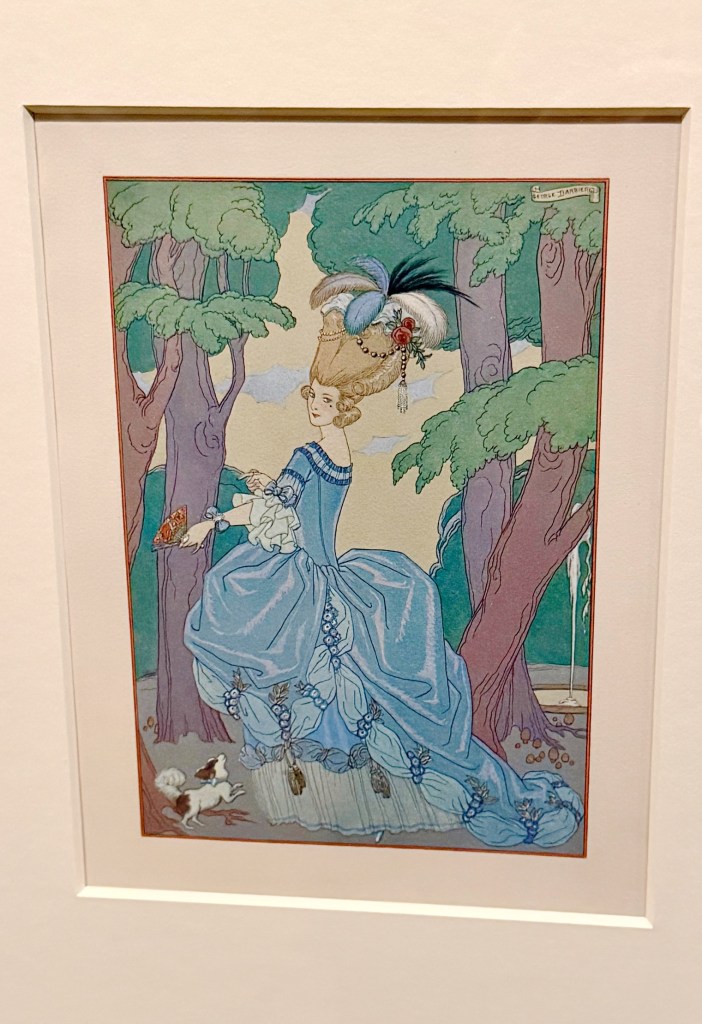

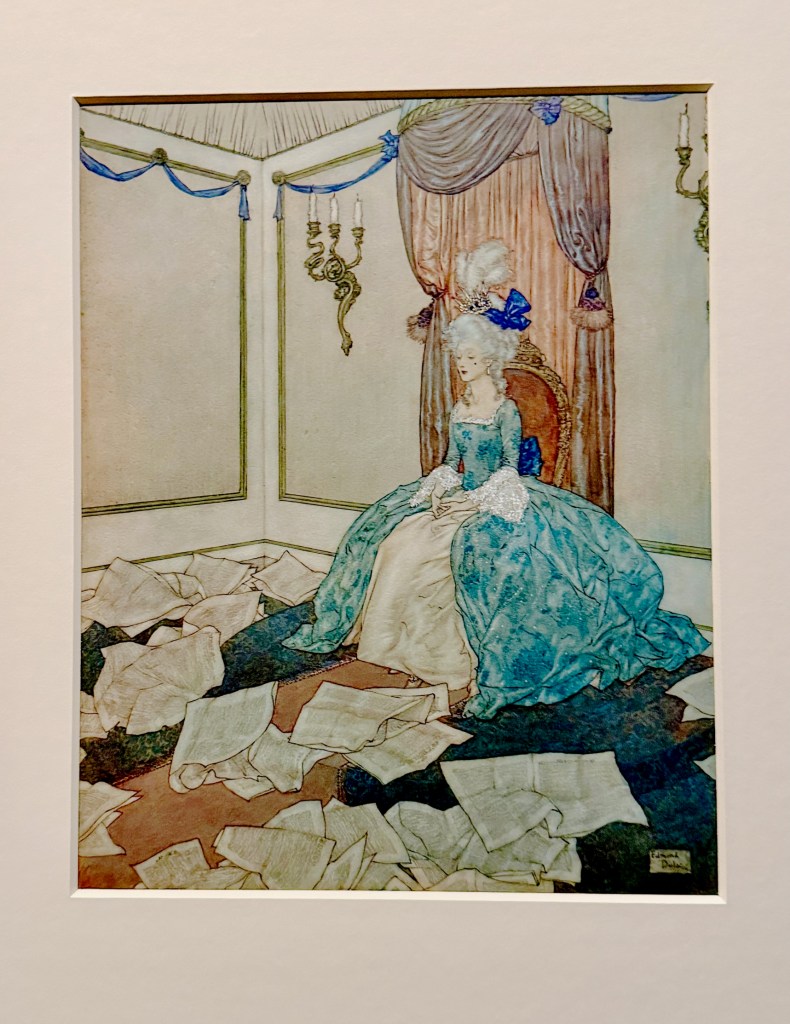

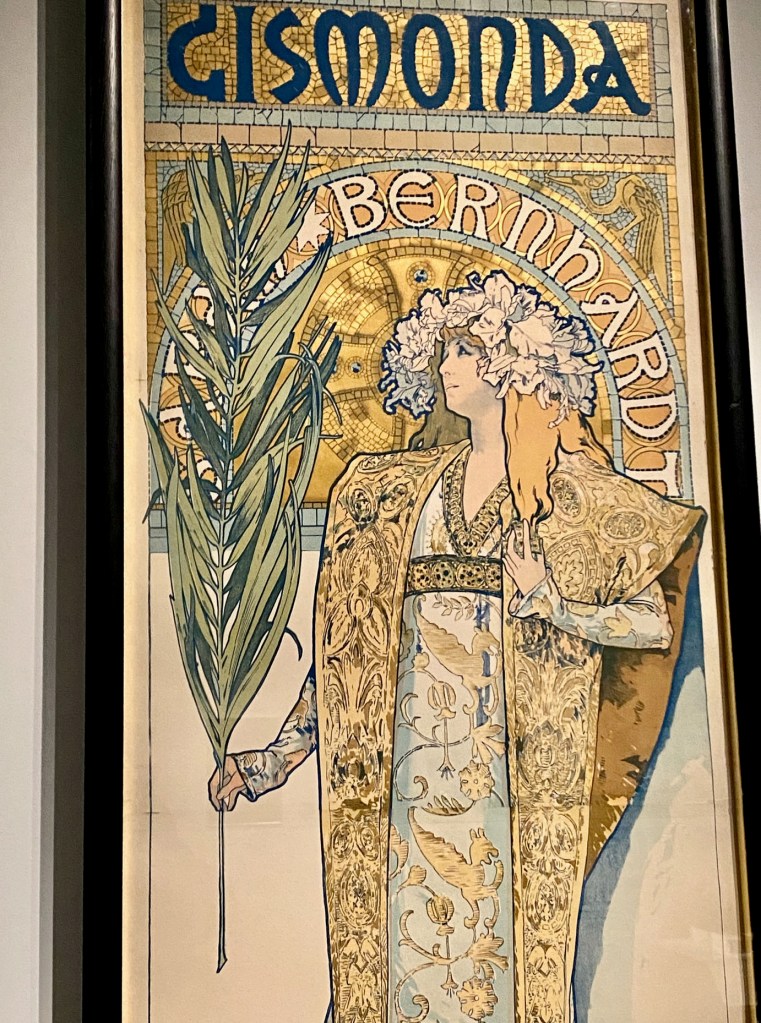

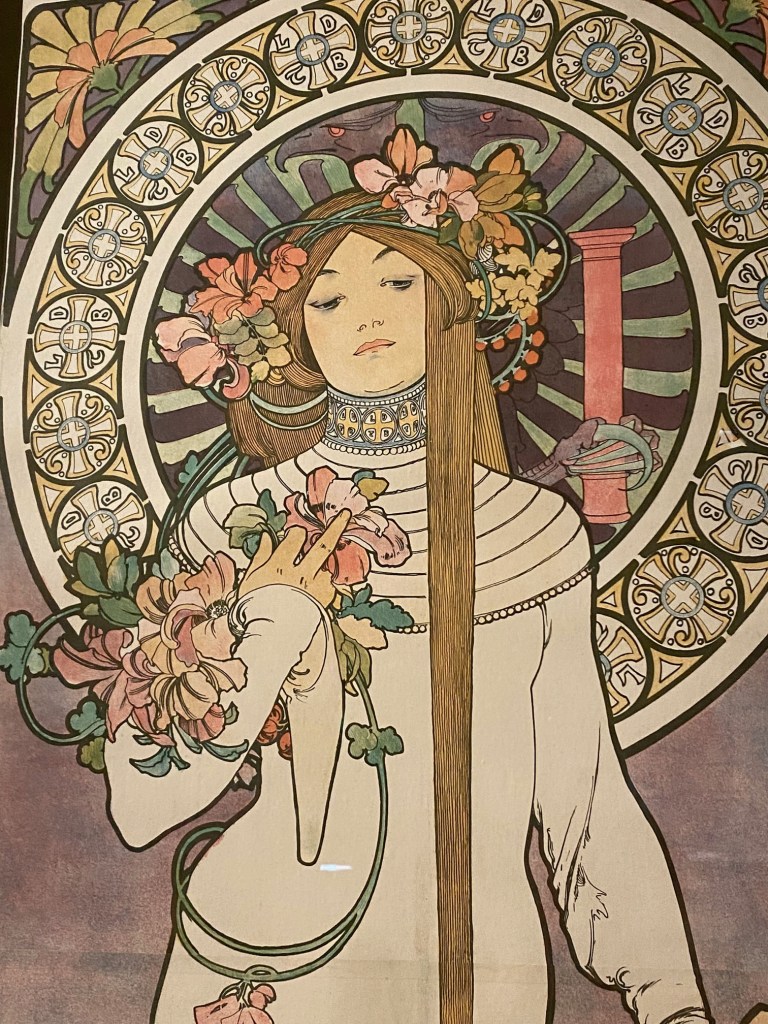

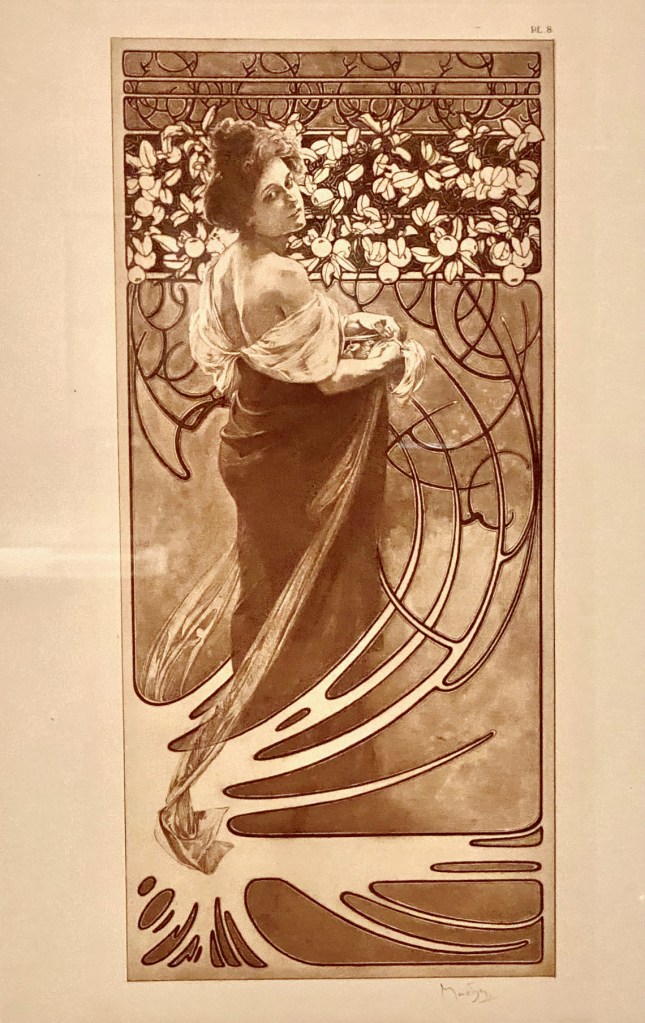

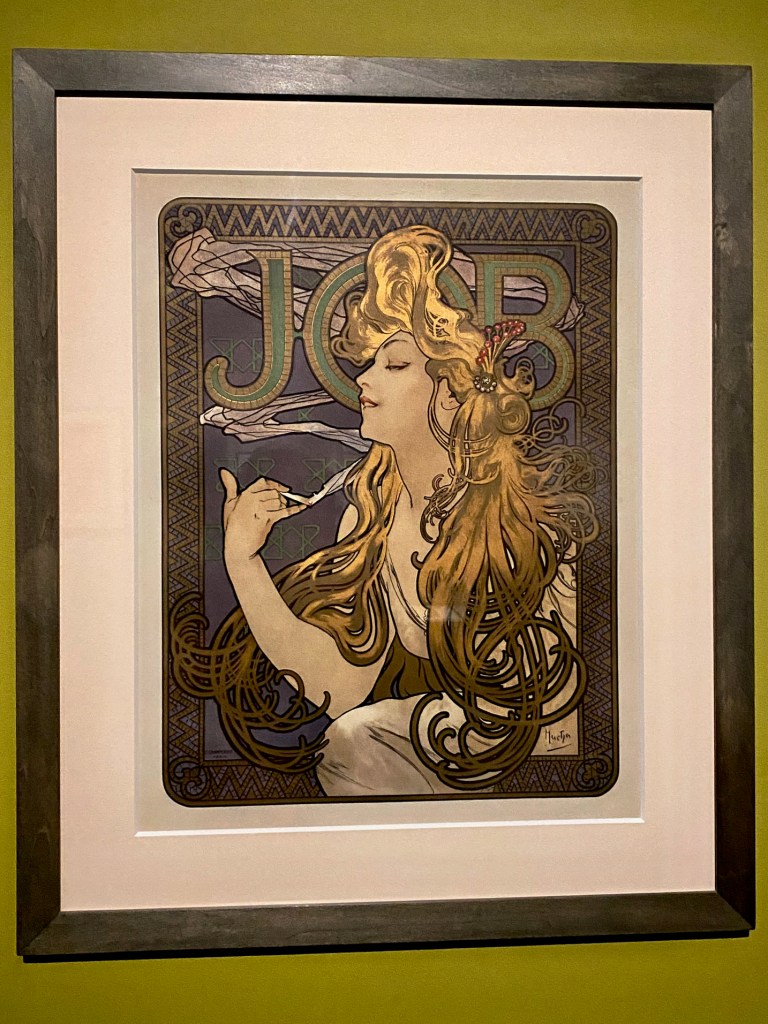

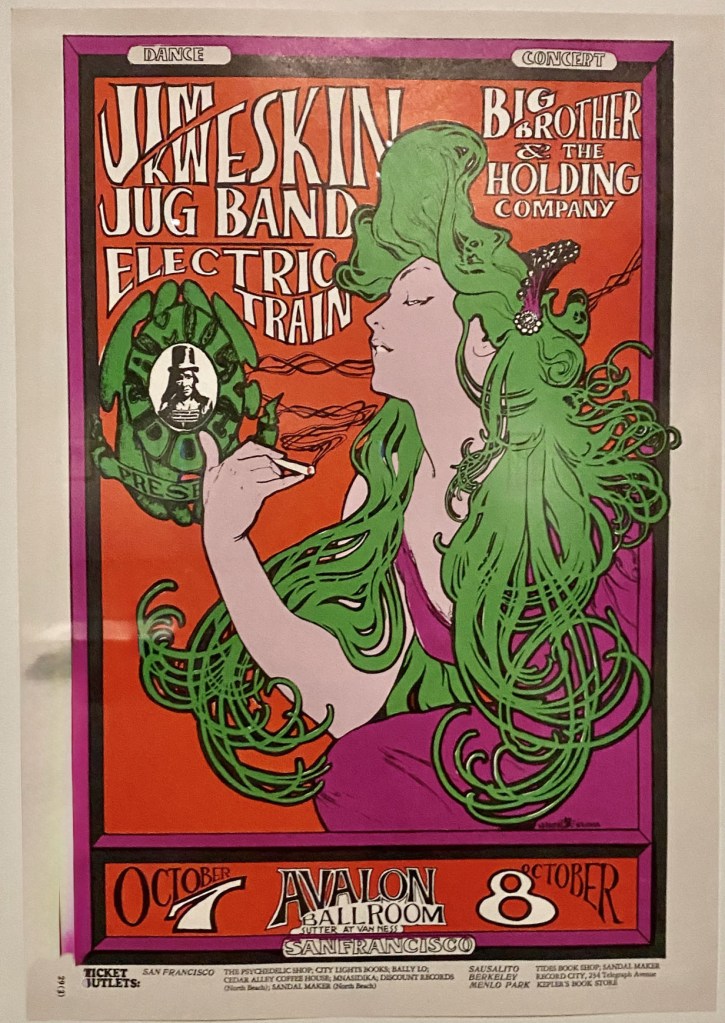

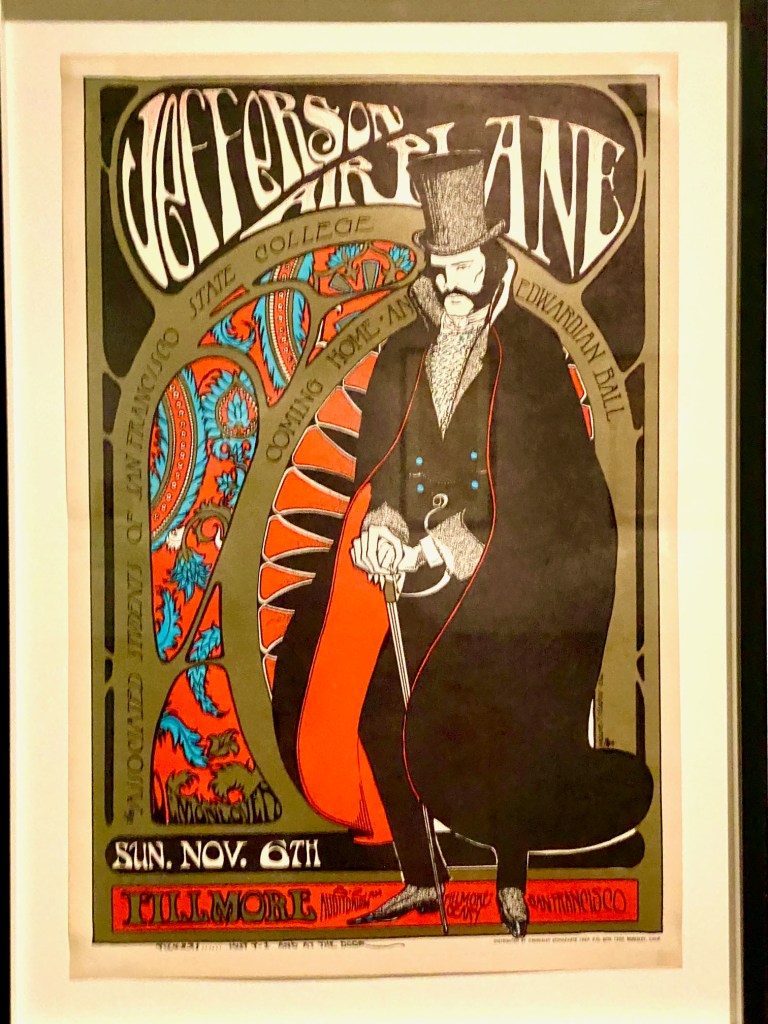

Spurred by Eugénie’s very public fandom into the 20th century, pop culture did not lose sight of Marie Antoinette as a style on display at upscale costume parties or as the evergreen image of fairy-tale princesses. The V&A shows illustrations using the queen’s pouf-do, tiny waist, princess-heel shoes, and voluminous 18th-century gowns to convey royal ingenues right into the 1910s and 1920s.

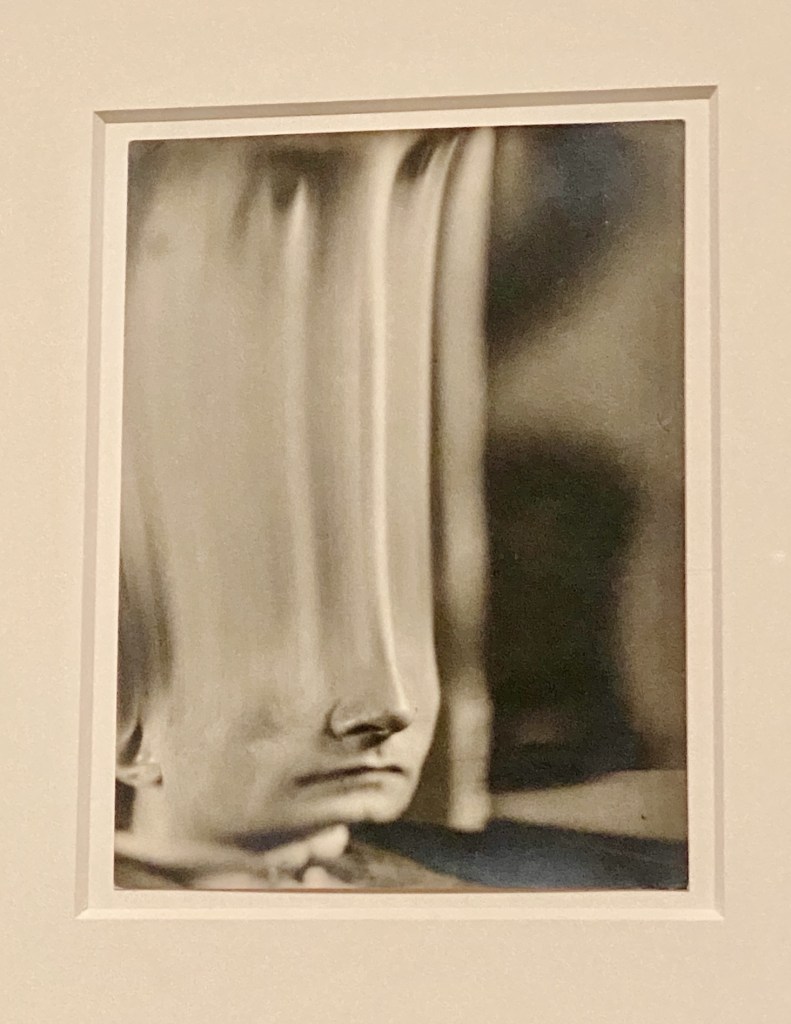

And 1920s fashion designers took note, mixing gauzy references to Marie’s muslin dresses with full skirts and panniers.

The spectacular finale to the exhibition pays tribute to the costume designers and haute couturiers who have translated Marie’s style into modern times. Even Manolo Blahnik jumped at the invitation to make shoes for Coppola’s Marie Antoinette film actresses, making each pair himself and basking in the glamor of using truly opulent silks and embellishments. It’s fun to see an entire wall of them.

The show closes with a bigger-than-big wide gown by Galliano for Dior, surrounded by two tiers of Moschino silicone cake dresses, Moschino toile de jouy pannier spoofs, Marmalade’s drag ensemble, Vivienne Westwood’s bridal take, and even Lagerfeld’s take on those scandalous diamonds for Chanel.

It’s an unmistakable style that’s recognizable hundreds of years later, and one everyone who’s seen this unforgettable show is still talking about!

Be forewarned: Schiaparelli opens at the V&A South Kensington on March 28, 2026.