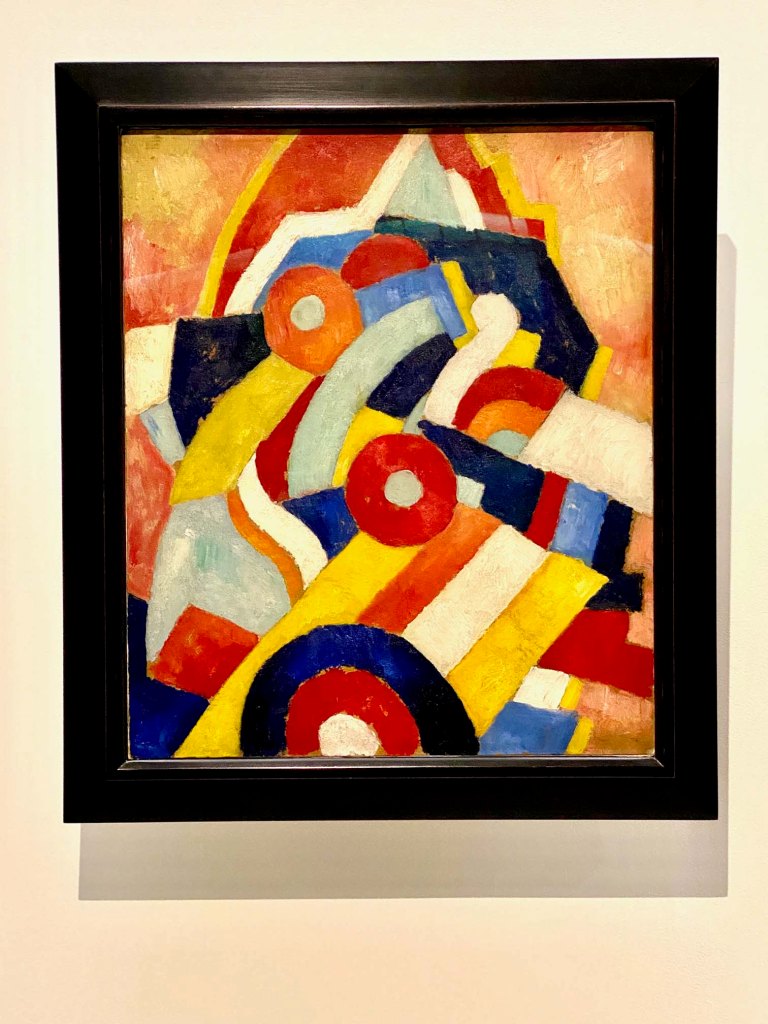

After Man Ray saw European Cubism at the 1913 Armory Show, he knew what he had to do in his own art – abandon all of the constraints of contemporary American art and dive headfirst into Dada and push the boundaries – go rogue.

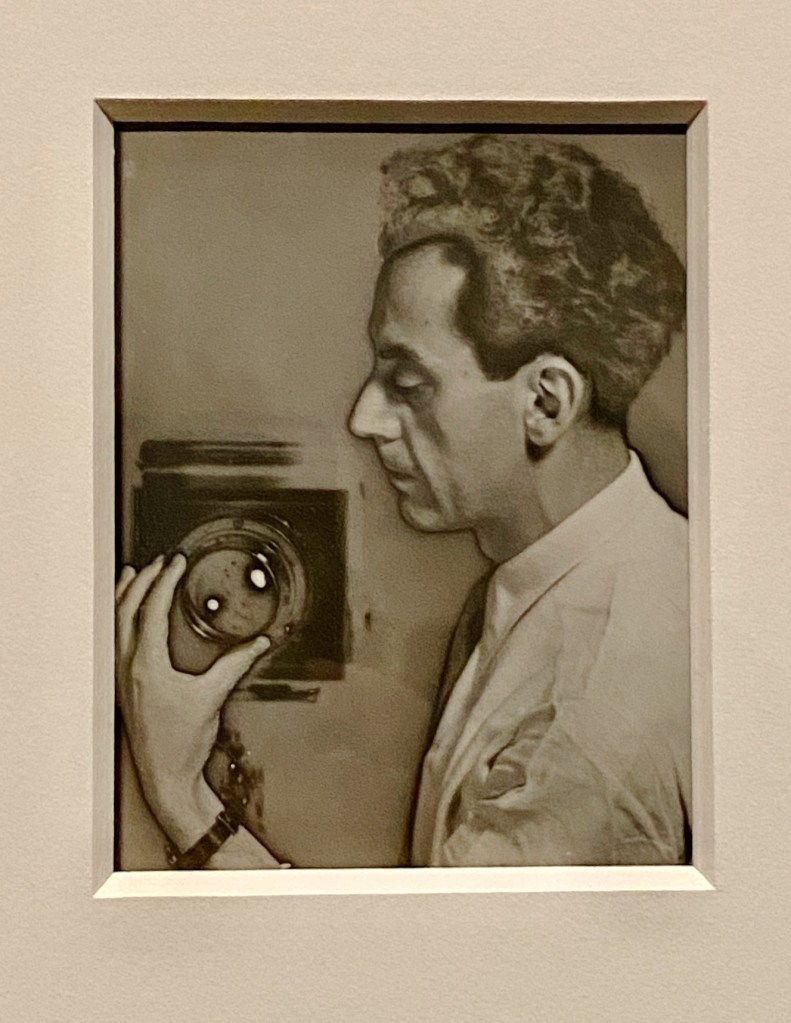

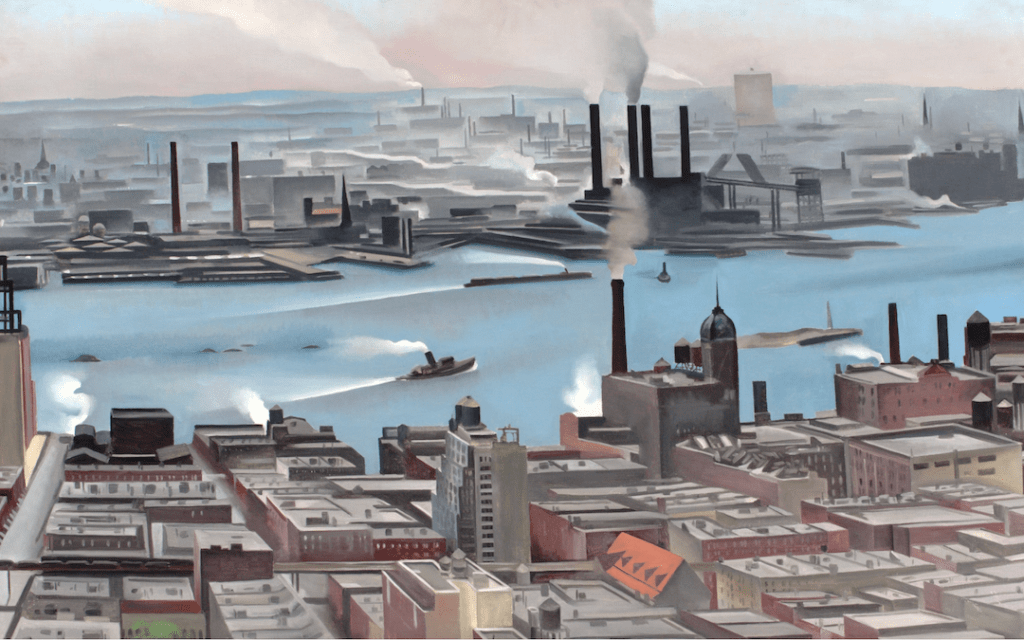

Some say that Man Ray became America’s most important 20th century artist. Marcel Duchamp – who became one of Man Ray’s best friends and collaborators – would certainly agree. All the evidence for Man Ray’s status is right here in the Met’s survey of Man Ray’s formative years (1914-1929), Man Ray: When Objects Dream on view through February 1, 2026.

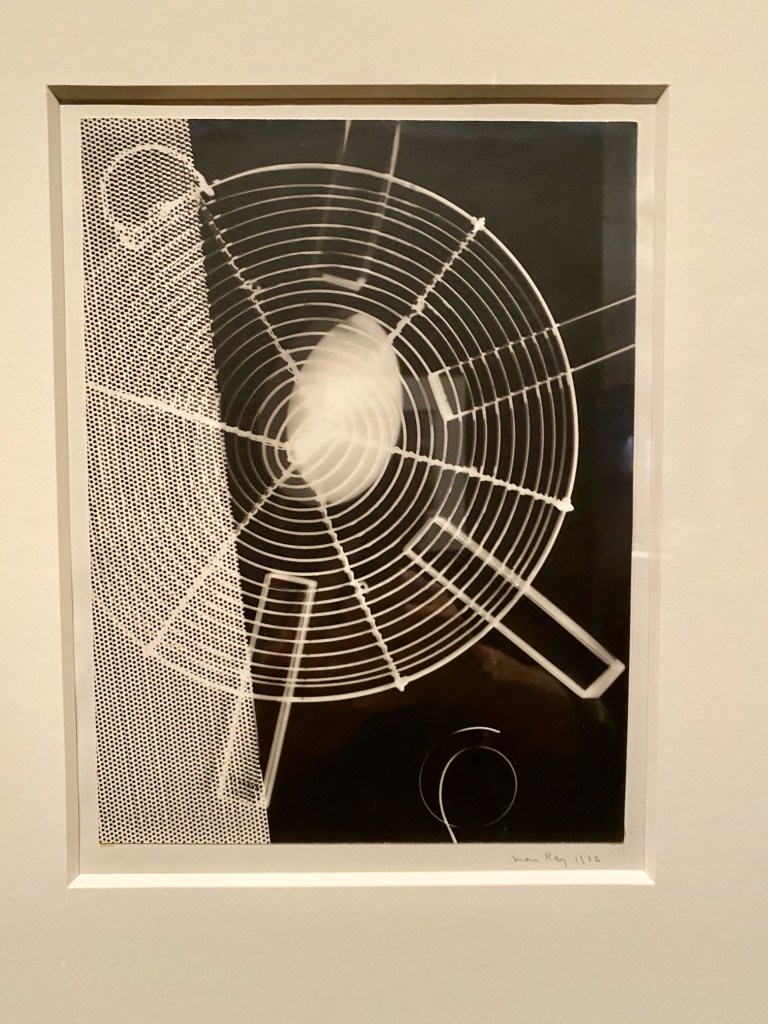

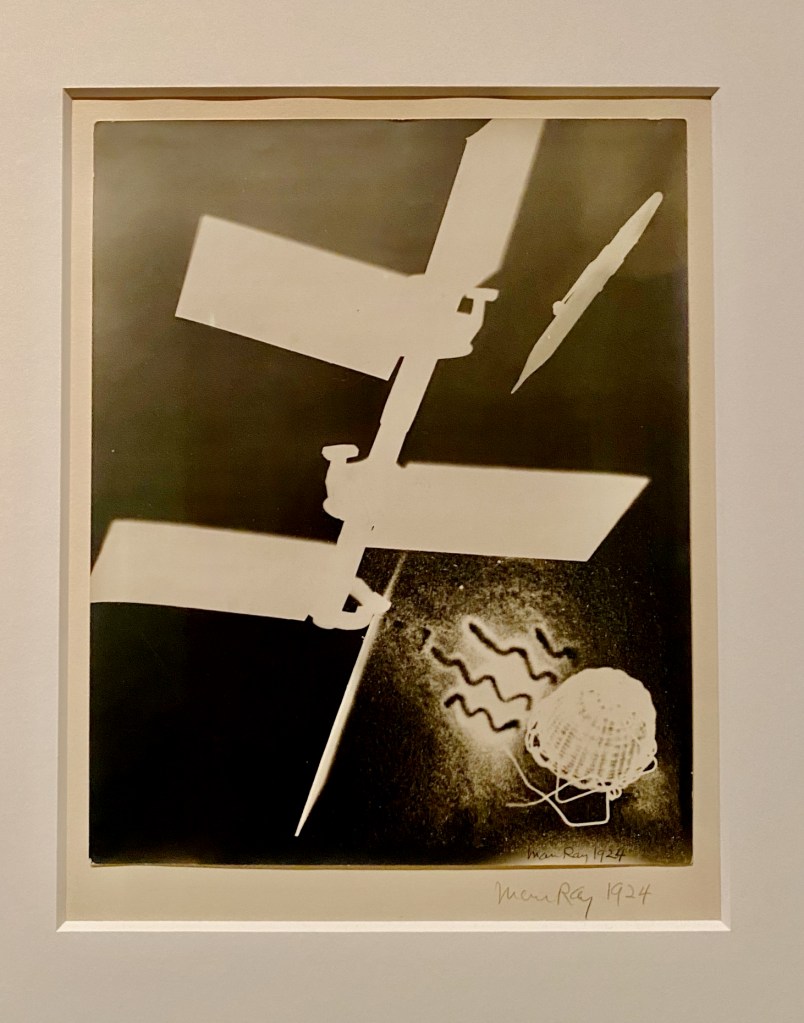

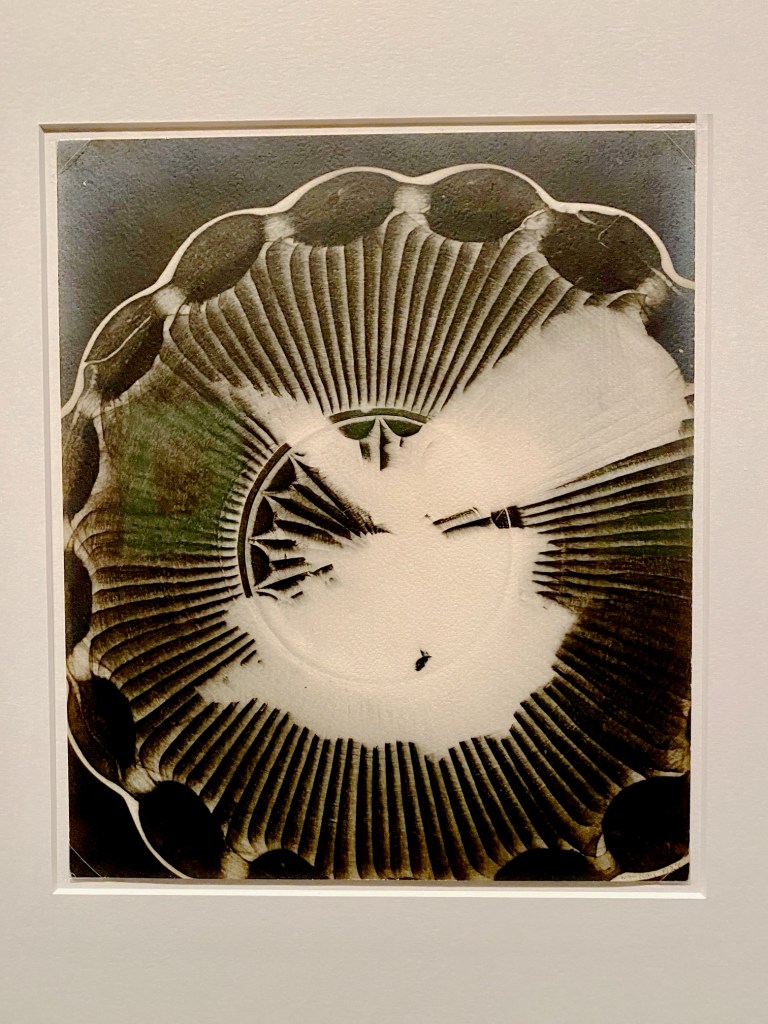

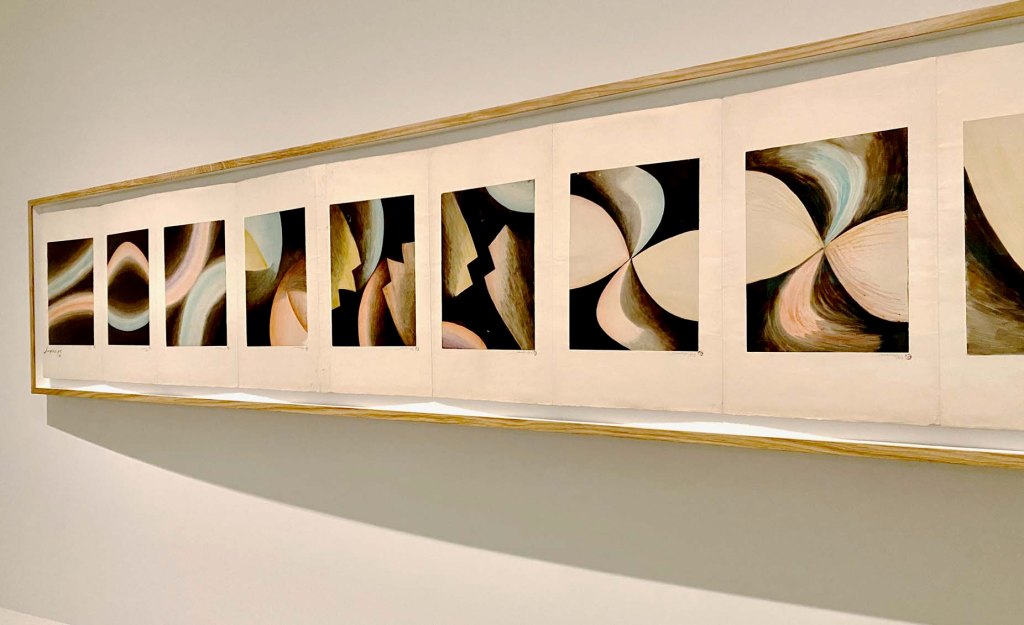

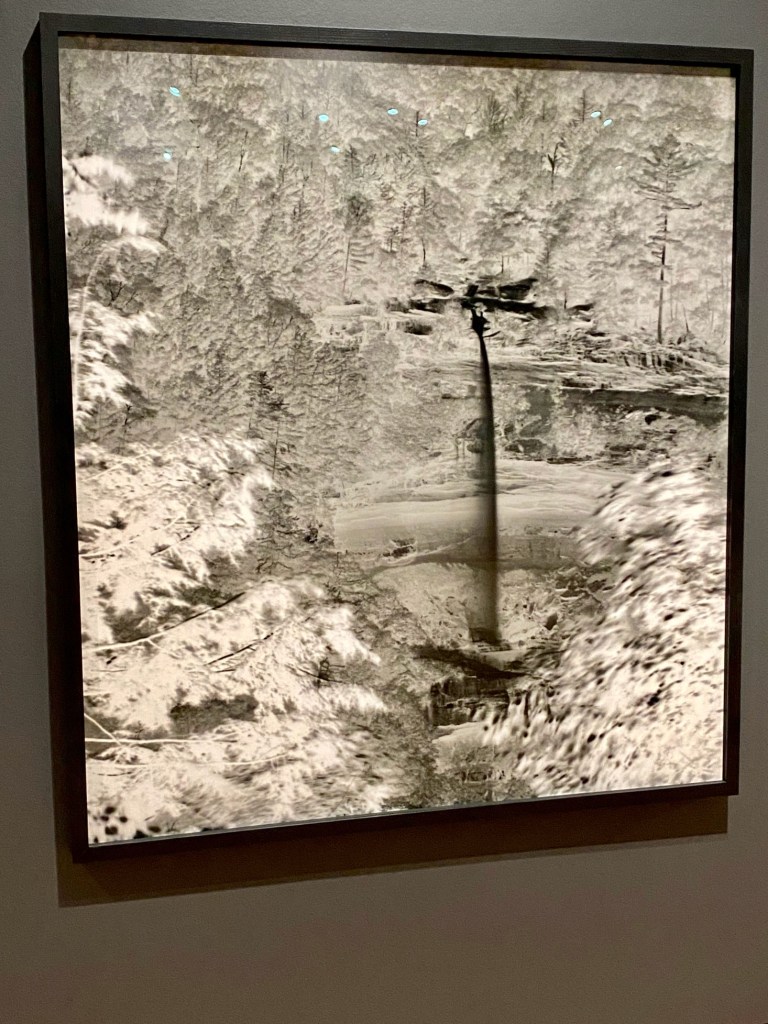

Walking in, you look through the exhibition’s architectural aperture to an endless array of Man Ray’s famed rayographs – dreamy abstract black-and-white cameraless images – lining parallel black gallery walls. Nearly sixty have been gathered for this occasion from international public and private collections.

See our favorite works in the exhibition in our Flickr album.

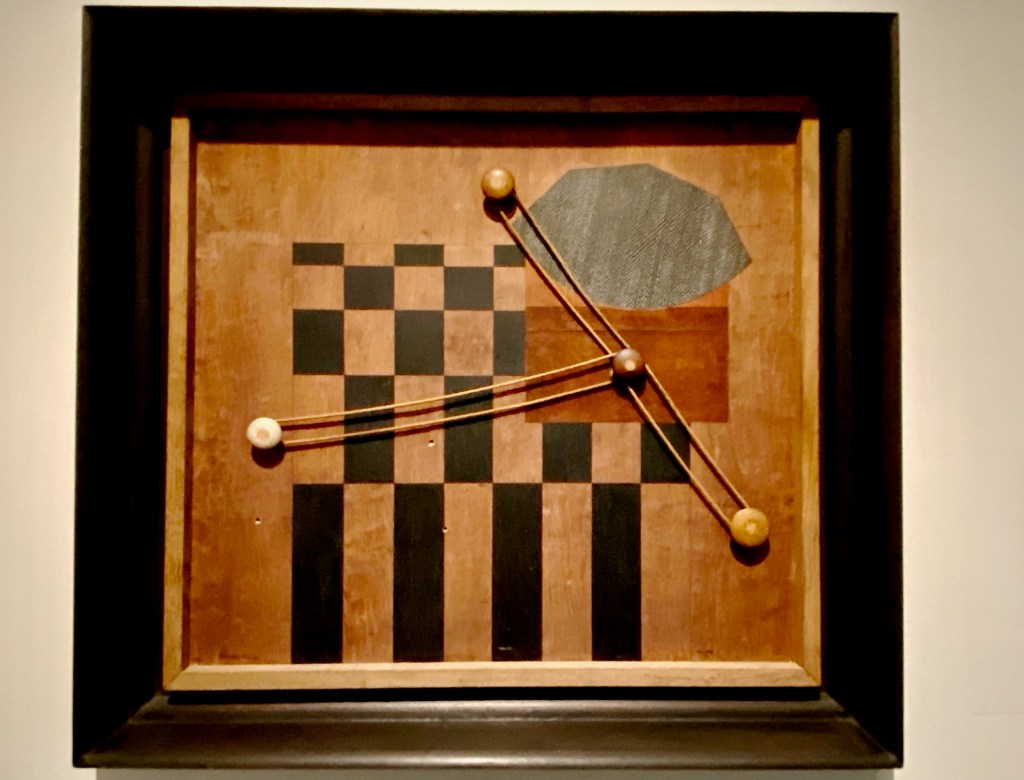

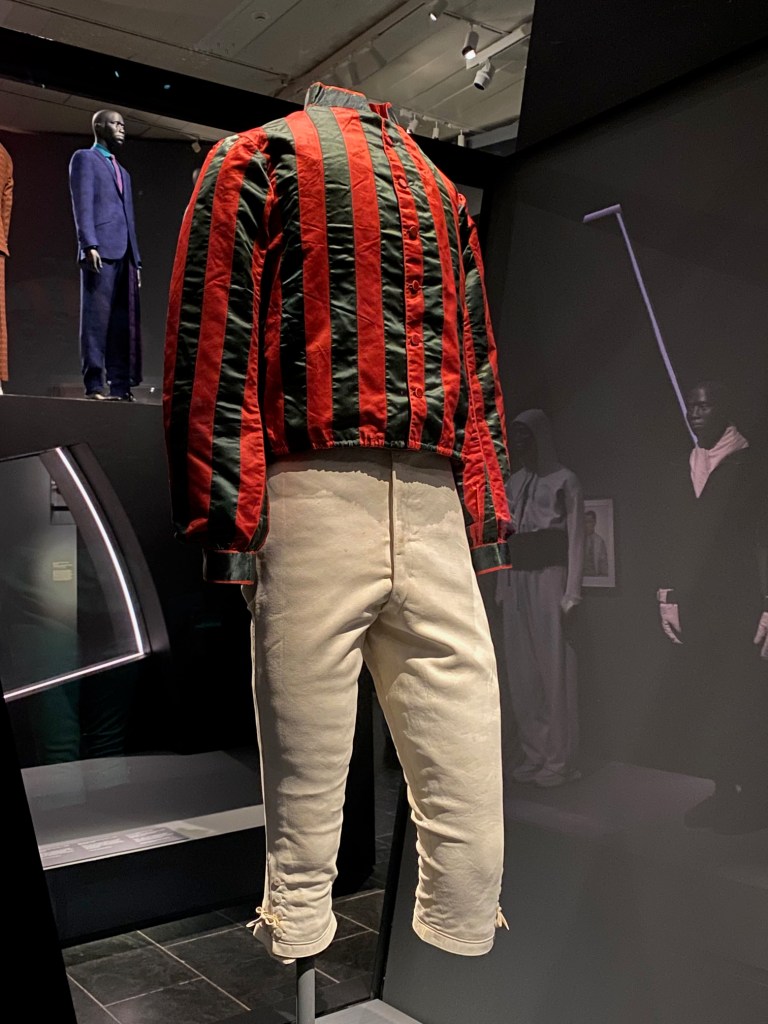

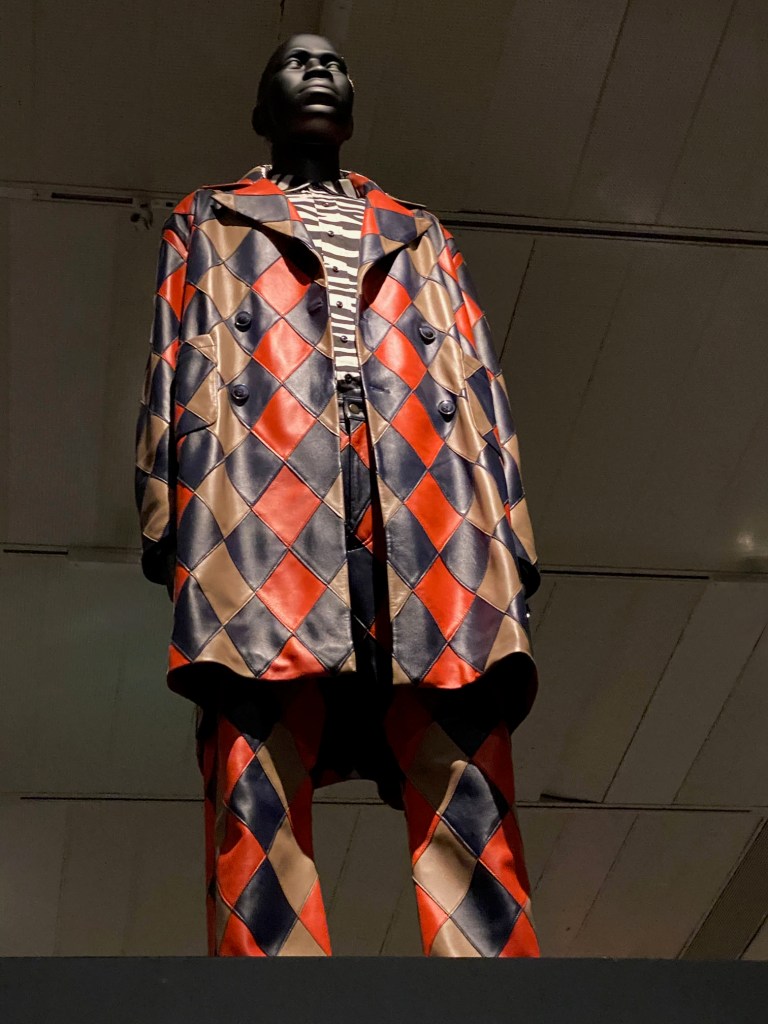

Although the rayographs form the core of this show, you also see the oil paintings, airbrush drawings, sculptures, movies, and game boards – works that are rarely seen, but illustrate why Man Ray rapidly took center-stage in the modern avant-garde community.

While working as a commercial artist and photographer, he used his free time to make unconventional, revolutionary works that banished representation. In 1916, he wrote a “new art” treatise on how to condense motion and dynamic shapes into two dimensions.

By 1917, he was making large-scale works, portraying a Rope Dancer mid-performance with stencils, cut-up pieces of colored paper, and big colored spaces representing her shadows.

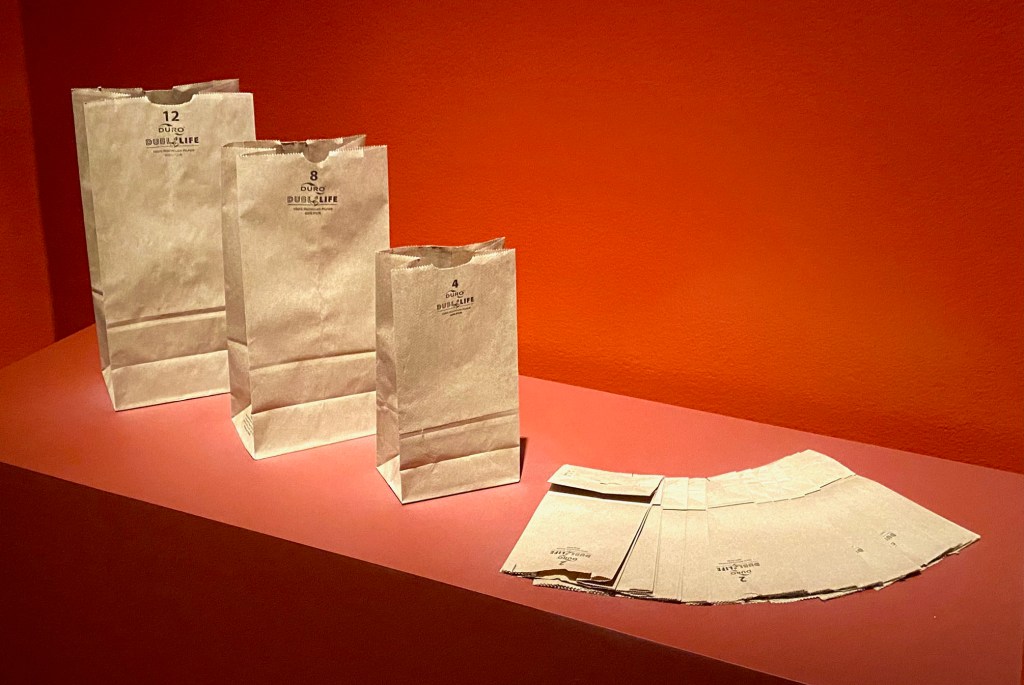

His sculptures were made in true anarchist-Dada fashion – from junk found on the street or in his apartment-building trash can. In one gallery, a precarious grouping of dramatically lit wooden hangars is installed overhead like a chandelier. The cast shadows look pretty good, too. His spiraling Lampshade, a sensuously curved metal sculpture is nearby, alongside paintings and avant-garde portraits where he repurposed the great shape.

He even made game boards and chess sets to symbolize his philosophy about the best way to make art – spur-of-the-moment imagination, abstract planning, clear intention, and an element of surprise.

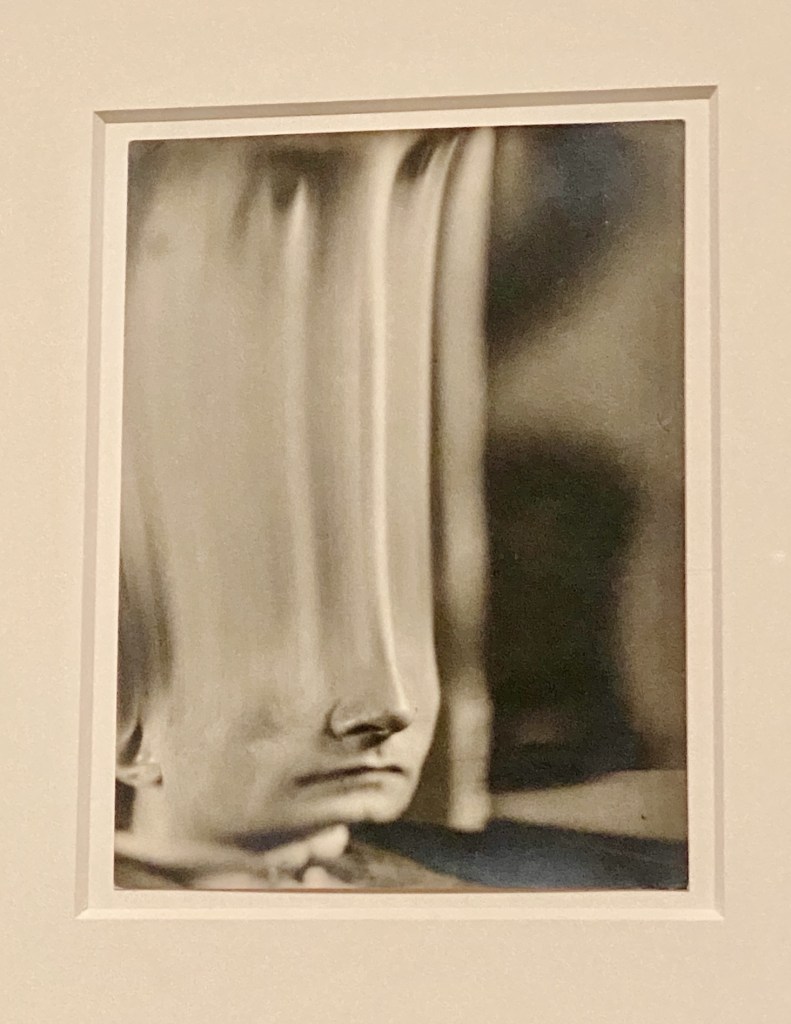

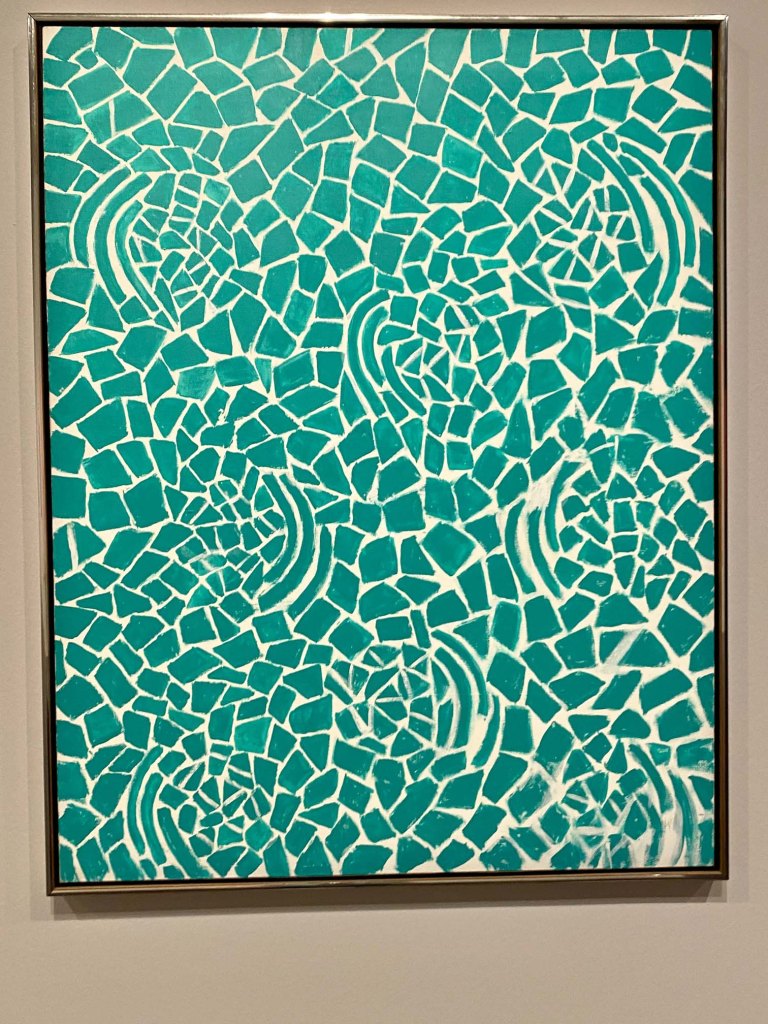

For Man Ray’s fine-art photographs, he preferred using inanimate, everyday objects to humans. And as he progressed as an artist, he didn’t use a camera. In 1917, he started making glass-plate prints (cliché-verre) with sinuous, patterned line drawings. Soon, he was innovating with Aerographs – abstract pencil-and-airbrush drawings inspired by new technology (“drawing in air”).

Man Ray primarily spent his time in Paris during the 1920s. Once he began making rayographs in his studio, he was content playing with unusual juxtapositions of everyday objects, studio lights, and various types of photographic exposures. It’s reported that in 1922, he created over 100 rayographs and abandoned painting altogether. (But he took it up again the next year!)

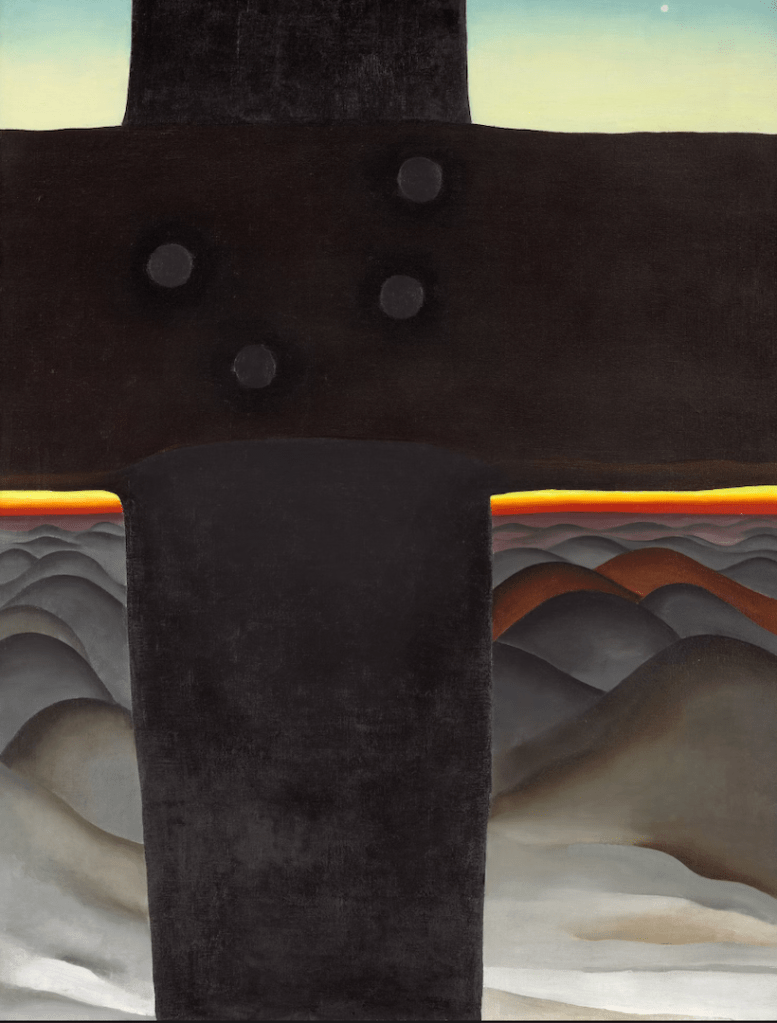

The curators make a point of juxtaposing several rarely-seen paintings with specific rayograms from the same period to make a point – the artist might have returned to experimental paintings as a compliment to some of the shapes and feelings he was exploring through photography.

His unusual, dream-like images were eagerly applauded by the inner circle of European poets and artists who would soon be the official founders of Surrealism. They were intrigued by dreams, psychoanalysis, inner worlds, and startling juxtapositions. In fact, the title of the Met’s show comes a phrase written by Man Ray’s fan, poet Tristan Tzara – “when objects dream” refers to Man Ray’s mesmerizing work.

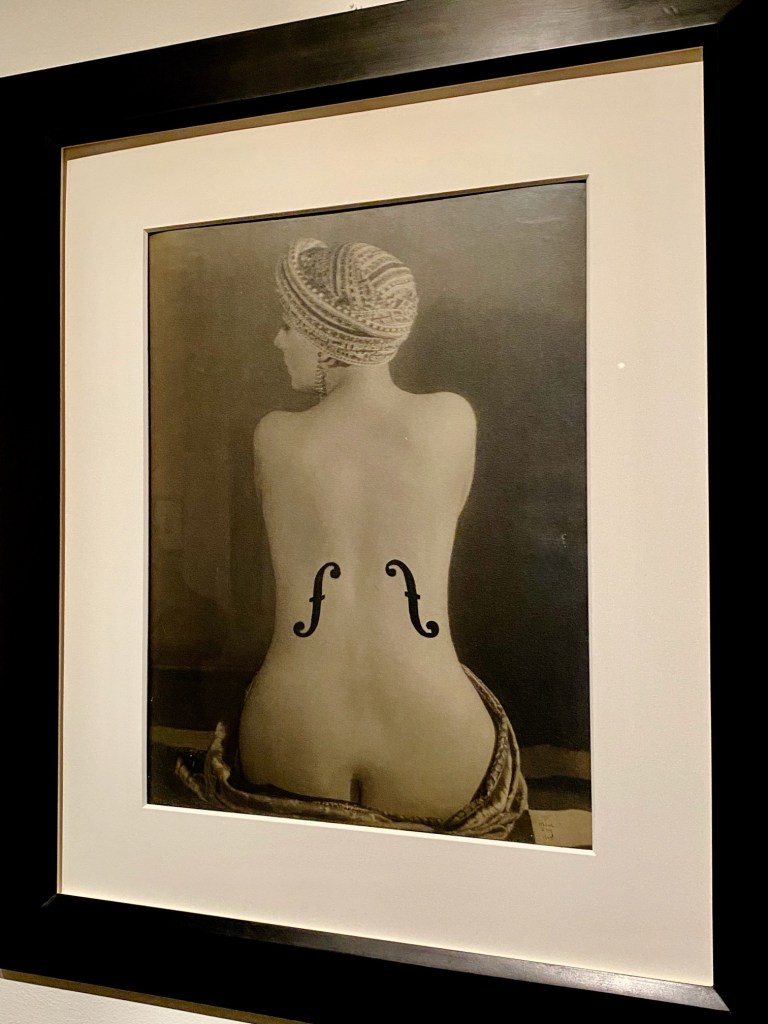

Man Ray’s ability to make magic with the camera – distorted images, adding surprising symbols, and creating tableaux of otherworldly floating objects – only added to the enthusiasm for his work.

The exhibition concludes with Man Ray’s beautiful solarized prints (a technique co-invented with model/photographer Lee Miller), symbolic paintings, and photographs that have become icons of Surrealism.

Hear the curators talk about the exhibition as they walk through this beautiful, inspiring show:

Take a look through all of the artwork in the exhibition here on the Met’s website. For more on Man Ray’s life and collaborations, listen to a longer Met telecast about his 1920s work with Lee Miller, Kiki de Montparnasse, and Berenice Abbott here.