It’s quite a leap from taking an art appreciation class with your daughter in your mid-thirties to assembling an enormous collection of paintings by radical art-world revolutionaries and anarchists. But that’s what one woman did and and the work is on display in Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists, on view at the National Gallery in London through February 8, 2026.

Crowds have been flocking to see incredible works by Seurat, Signac, and Van Gogh, and meet the Dutch and Belgian painters who adopted their breakthroughs and ran with these innovations for two decades at the end of the 19th century.

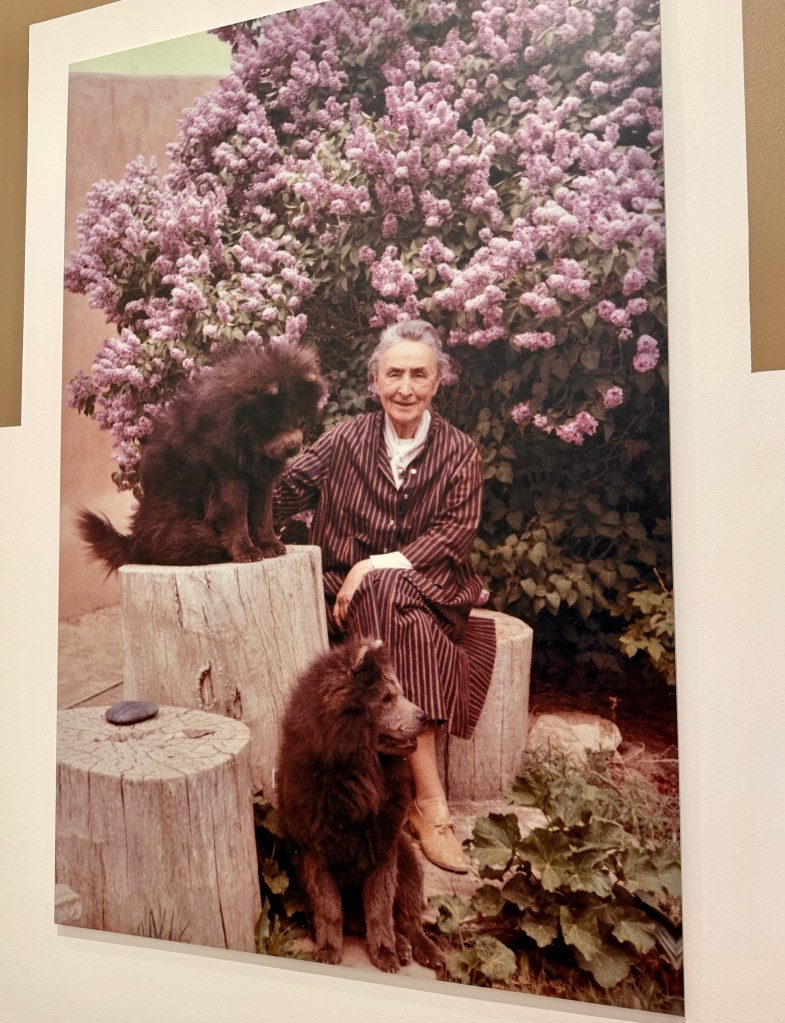

Maginificent, much-loved works were collected in the early 20th century by Helene Kröller-Müller, the daughter of a wealthy German industrialist. Her husband ran businesses for her father (and eventually his entire company) in Rotterdam, where they lived.

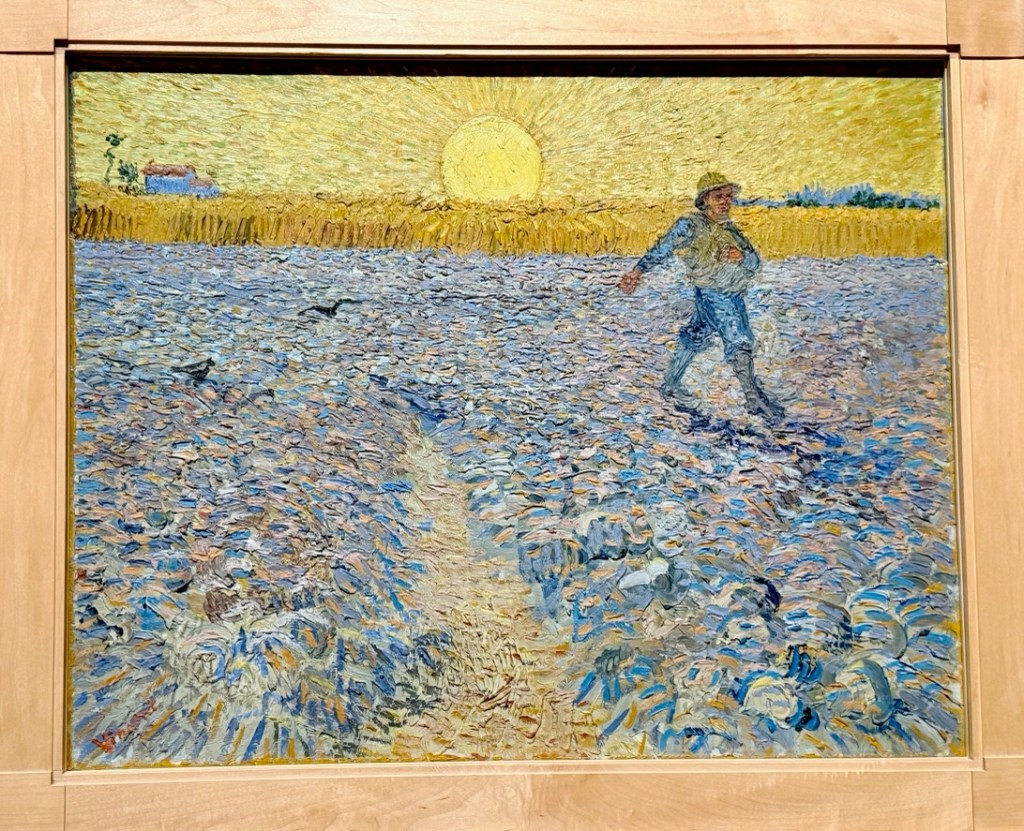

Helene was always encouraged to follow her intellectual interests, and new ideas. After taking a class about art in 1905 from Dutch artist/dealer/critic H.P. Bremmer, Helene began to understand why the radical colors, compositions, and subjects in paintings by Van Gogh, Seurat, and others moved her so deeply. Working with Bremmer as an advisor, Helene eventually amassed the largest collection of Van Gogh paintings and drawings in the world (outside of the Van Gogh Museum itself).

Helene sometimes accompanied Bremmer on buying trips with the goal of creating a public collection where people could see and experience the genesis of modern art. In 1912, they even visited Signac in his studio, where Helene purchases two magnificent tranquil harbor views – one by Signac and one by his late friend, Seurat.

Here’s a brief video about Helene Kröller-Müller’s passion for art, how she built her massive collection, and the beautiful museum in the Netherlands countryside that should be on every art lover’s bucket list :

This gorgeous exhibition in central London shines a light on this visionary collector, but the focus is less on Helene’s history and fully on her stellar collection of Neo-impressionist painting and related works from the National Gallery and other collections. See some of our favorites in our Flickr album.

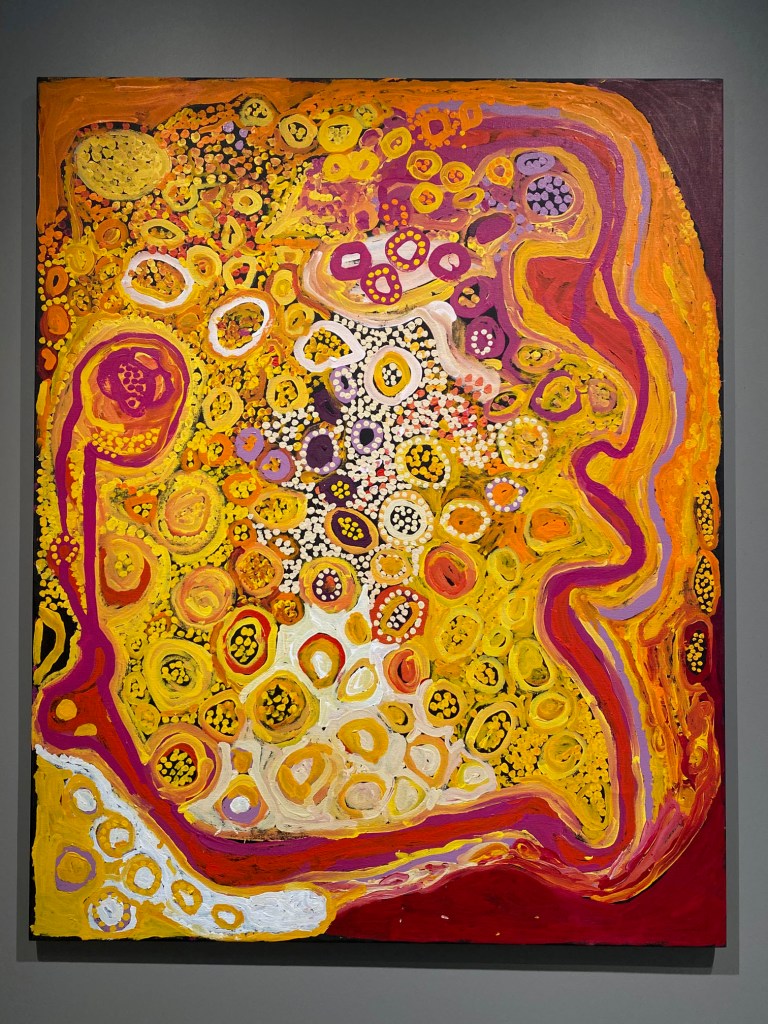

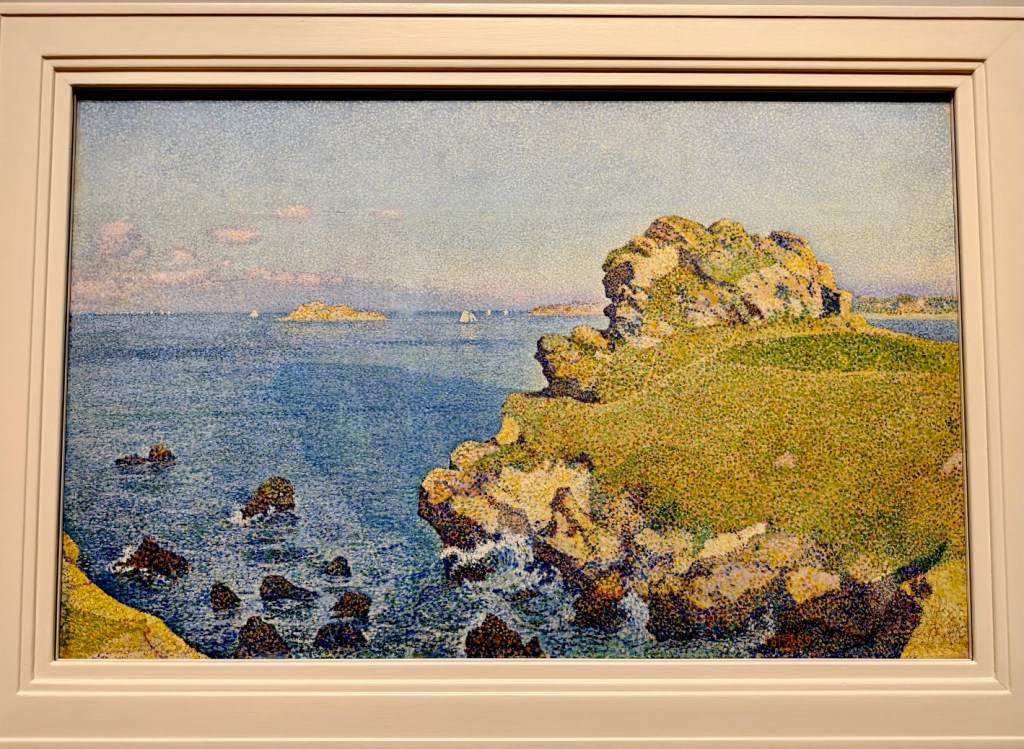

The exhibition begins with paintings by Seurat and Signac, who adopted color theory for their pointillist techniques to create shimmering images of simplified, tranquil harbors and seascapes. This new radical painting approach electrified artists across Europe, such as Belgian painter Theo van Rysselberghe and Dutch artist Jan van Toroop, whose works are also hung in the first gallery.

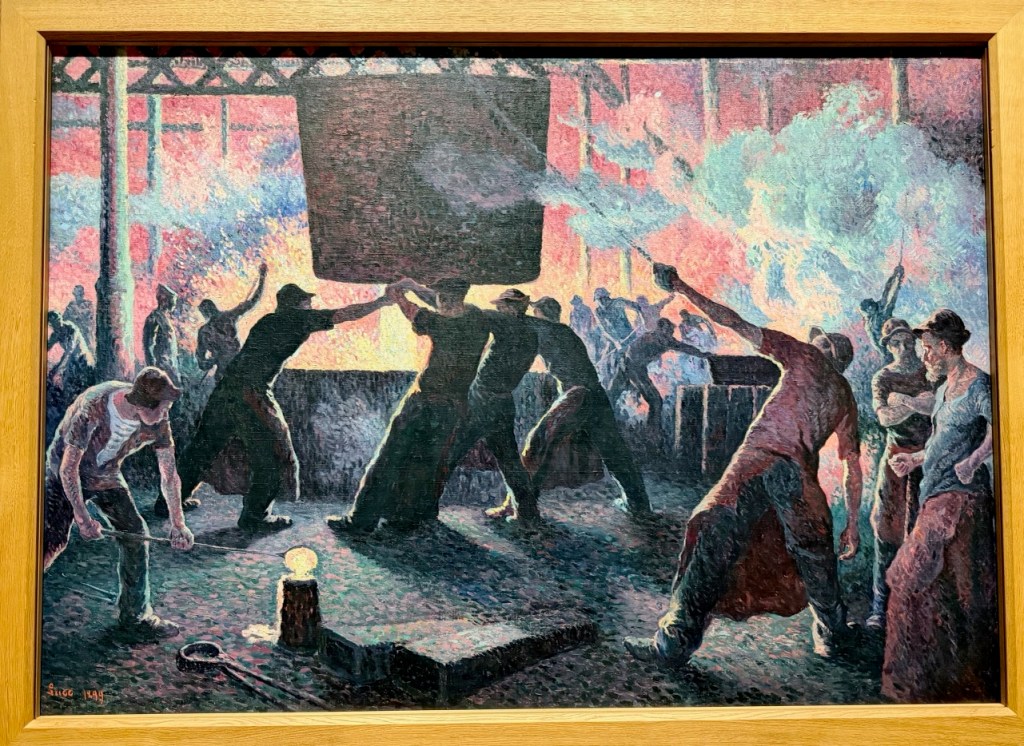

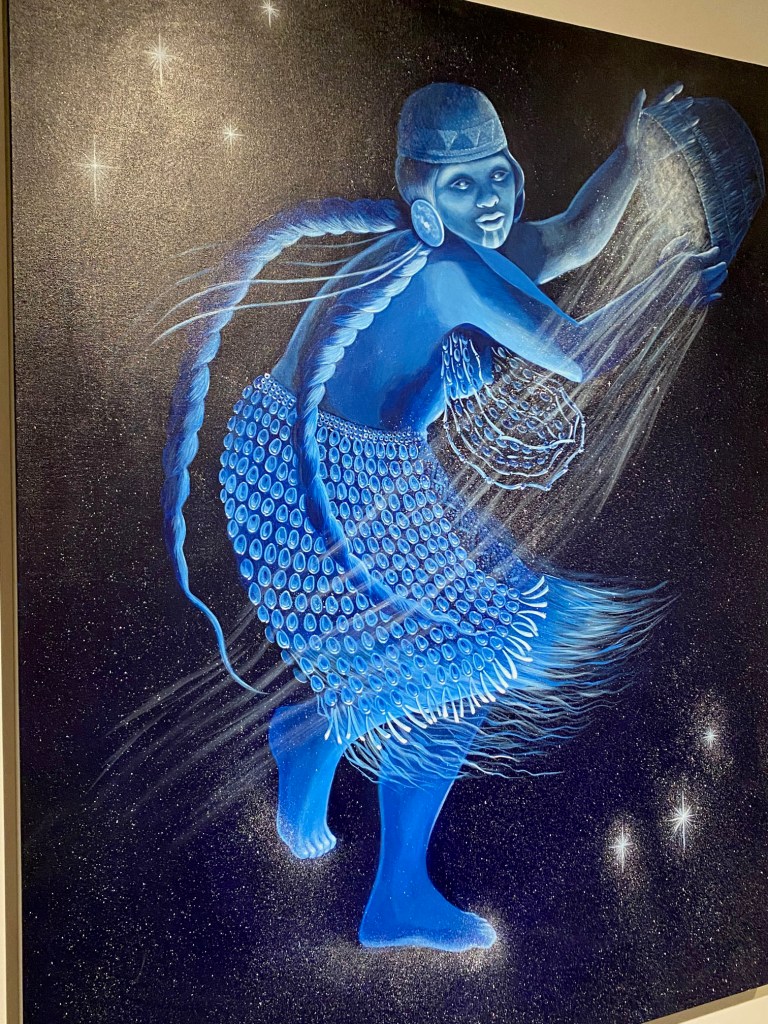

At a time when industrialization was transforming life, Helene did not shy away from acquiring works made by artists proud of their radical, progressive politics. Many of the artists featured in the exhibition were proud to call themselves anarchists – passionate radicals who used art to advocate for workers’ rights, elevate the image of working people, and create a hope of increasing harmony with nature.

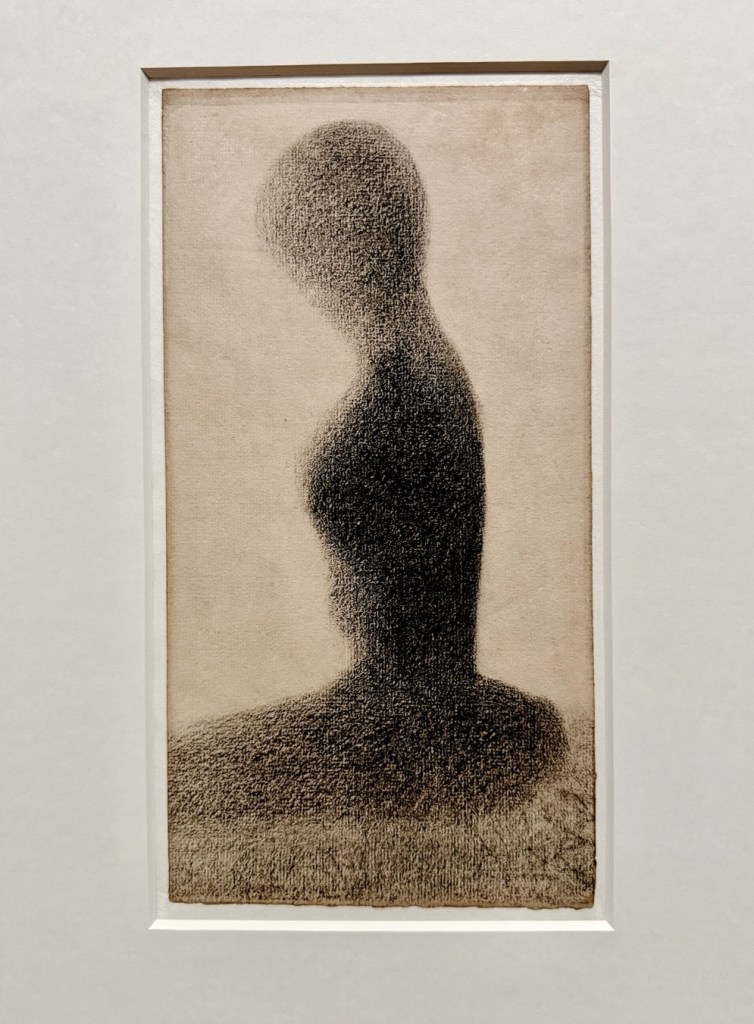

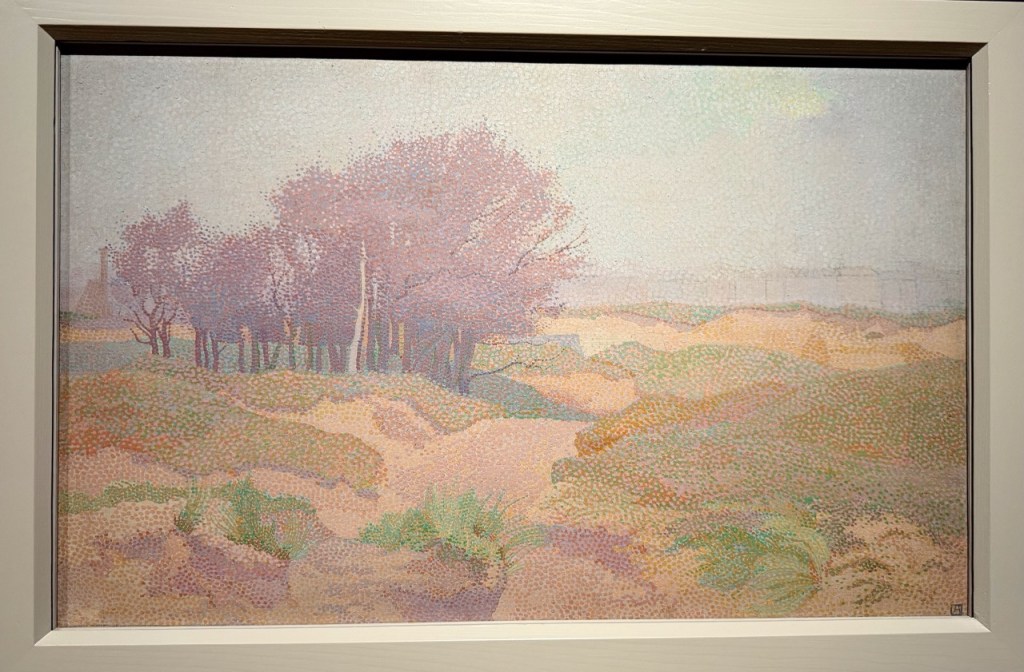

To create the pictoral harmony that they sought, these painters often stripped details out of landscapes. When people are present, they are depicted with highly simplified, streamlined faces – pleasing, but impersonal. These stand in contrast to paintings by Belgian and Dutch painters who applied their new color techniques to beautiful large portraits of their politically progressive friends and patrons.

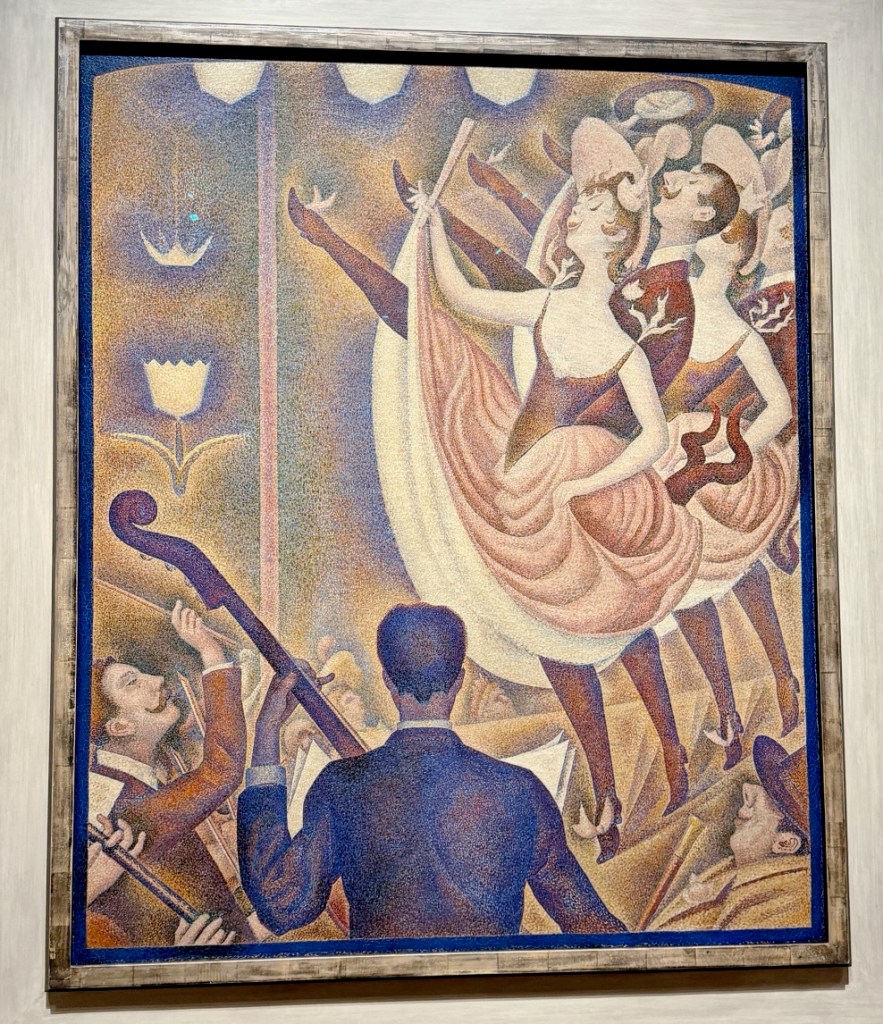

The centerpiece of the show is Seurat’s enormous painting of the scandalous can-can dance at a raucous late-night Paris venue. It’s the biggest, baddest, Neo-Impressionist work in Helene’s collection. The curators surrounded it with works showing how much other radical painters enjoyed music and nightlife.

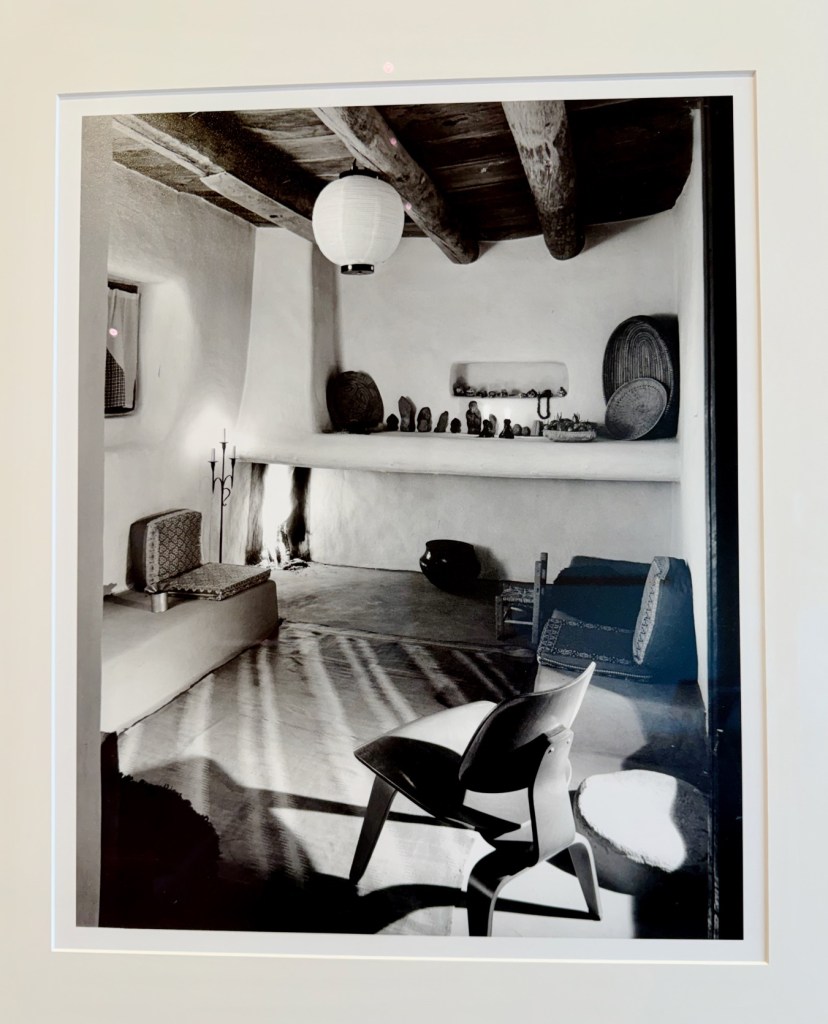

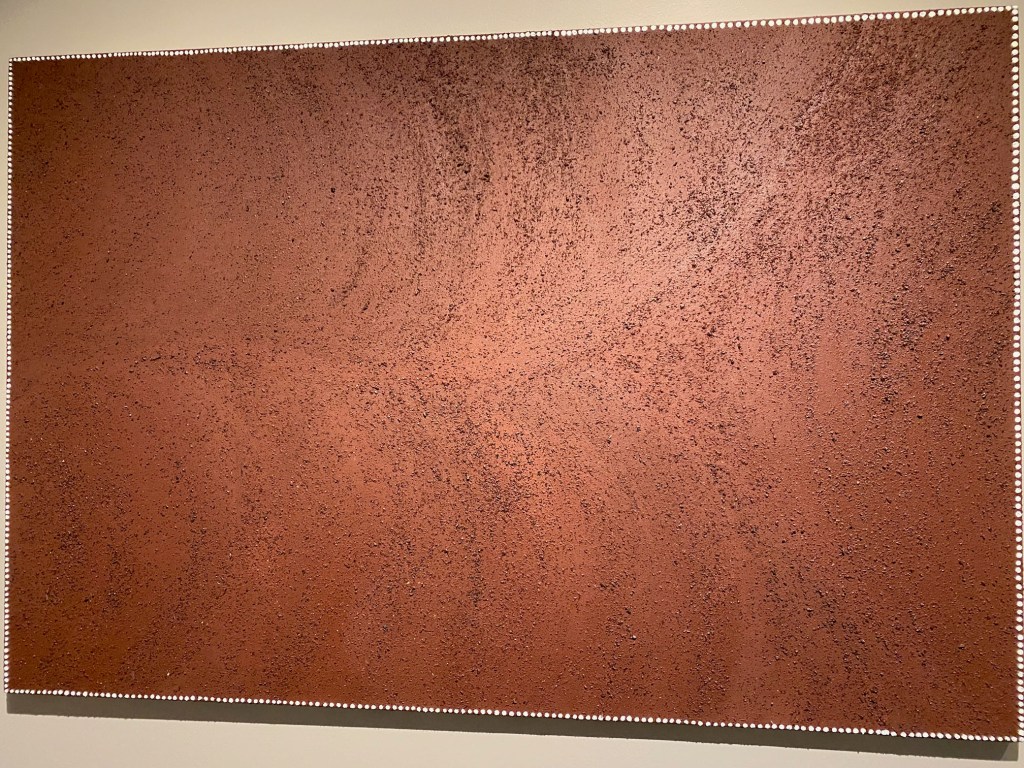

But just beyond this gallery, you’re surrounded by still, quiet domestic interiors and sun-dappled garden scenes in a gallery titled “The Silent Picture.” People are introspective, lost in thought, or lost in a book. Helene loved collecting large-scale works that seem to envelope viewers with stillness and calm.

And she truly loved the serene, nearly empty landscapes that this group of painters created. The long horizon of the sea only adds to these works’ peaceful presence. Helene wanted her museum to have clean lines, and unadorned galleries so that visitors could stand, contemplate, and find peace with these works. She truly felt these new, modern paintings had the ability to provide respite and even feel something spiritual.

Take a walk through this incredible show with the curators from the National Gallery, and hear how Seurat, Signac, and their contemporaries broke the rules and made history: