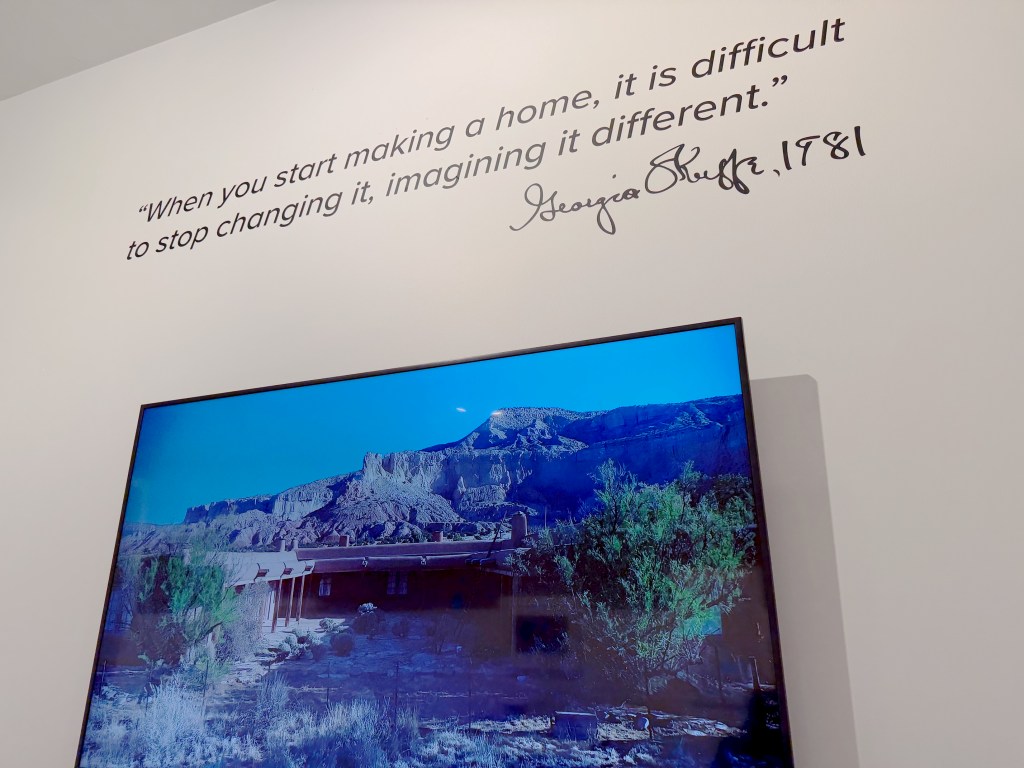

How do you turn a 200-year-old adobe home into a temple of mid-century modern design? See how Georgia O’Keeffe did it in Artful Living: O’Keeffe and Modern Design, an exhibition available on-line and at the GOK Museum’s Welcome Center near her home and studio in Abiquiu, New Mexico through January 31, 2026.

When Georgia bought her second New Mexico home in 1945, it was a wreck. All the better, for her to envision the possibilities of her dream house. Why was she obsessed with this? It had a home garden and irrigation, a placita in the center of the house with a working well, the iconic black door in the red wall, and an incredible view of the stunning landscape (and Pedernal).

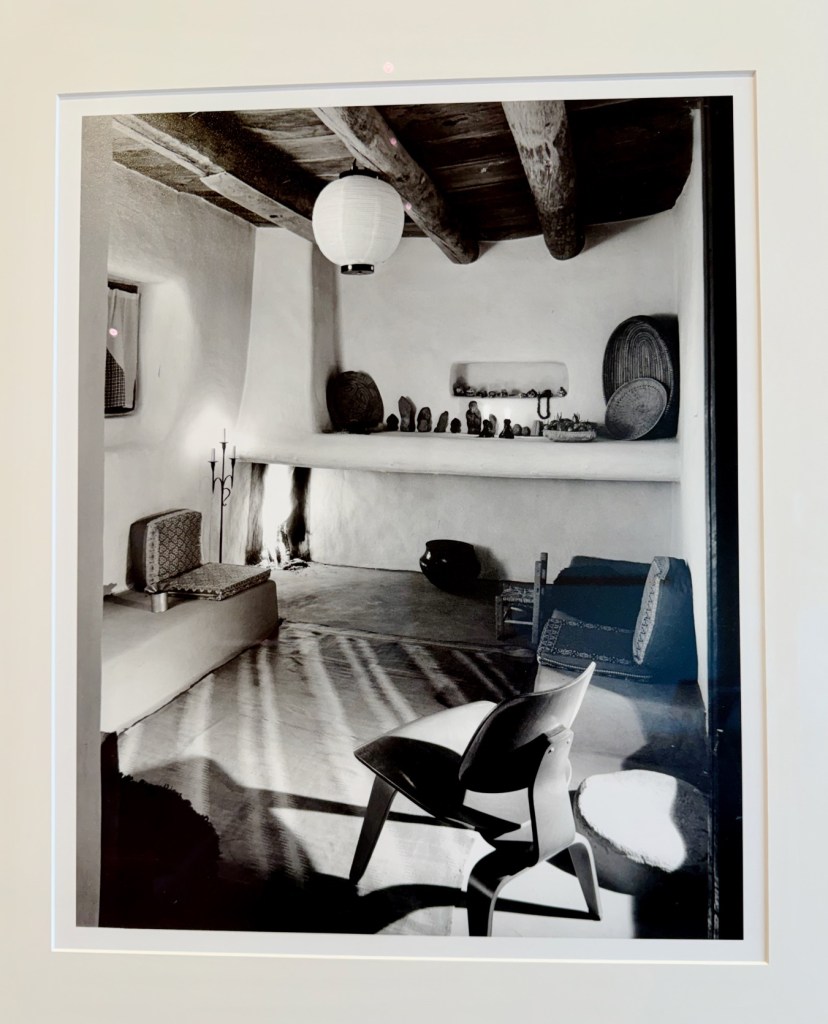

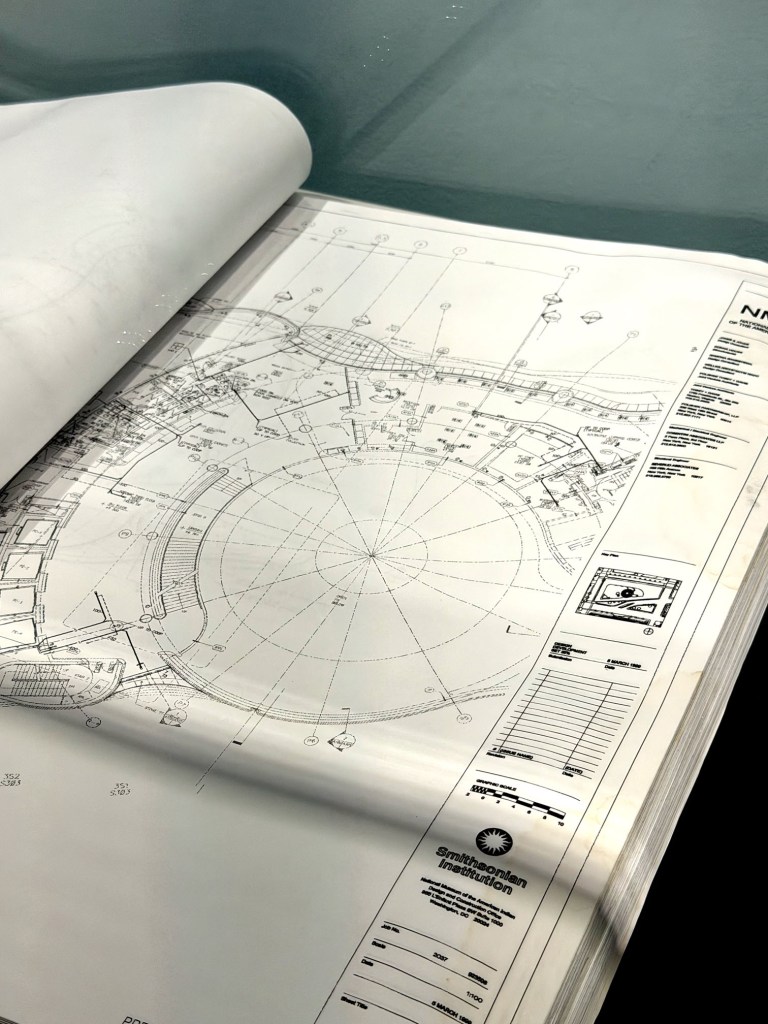

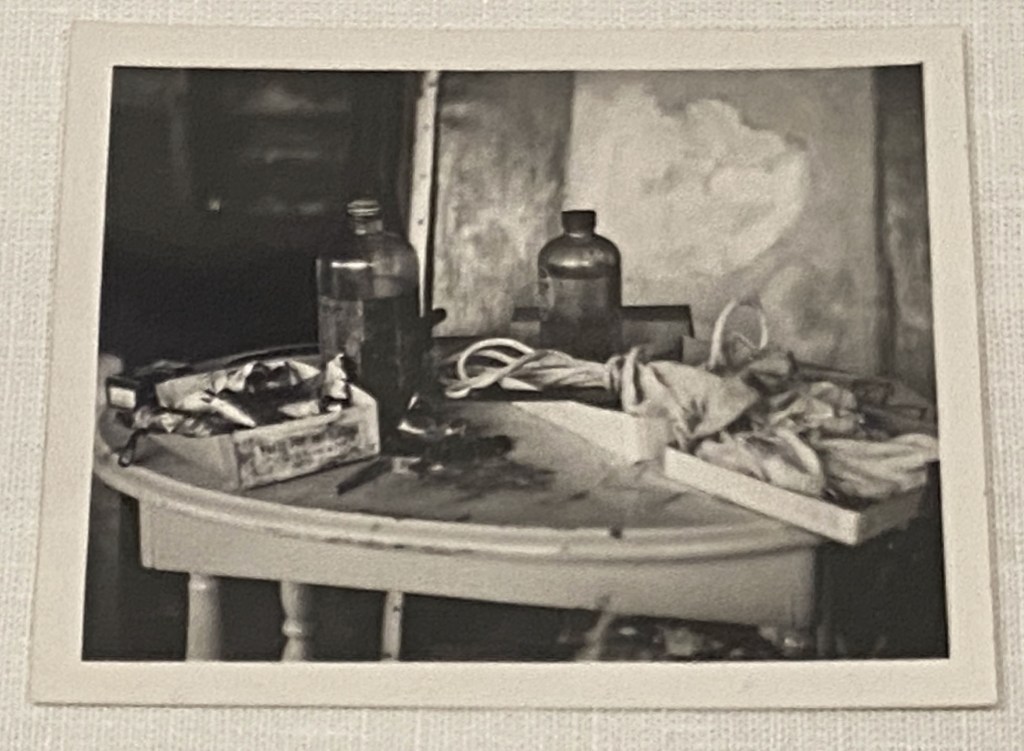

By collaborating for the next four years with her friend and project manager Maria Chabot, the property was transformed into a showcase for everything modern – furniture, fabrics, lamps, tableware, and (eventually) architectural innovations like skylights, gigantic picture windows, and open-plan living. To keep her creative sparks going, Georgia never stopped rearranging, adding, and switching things up.

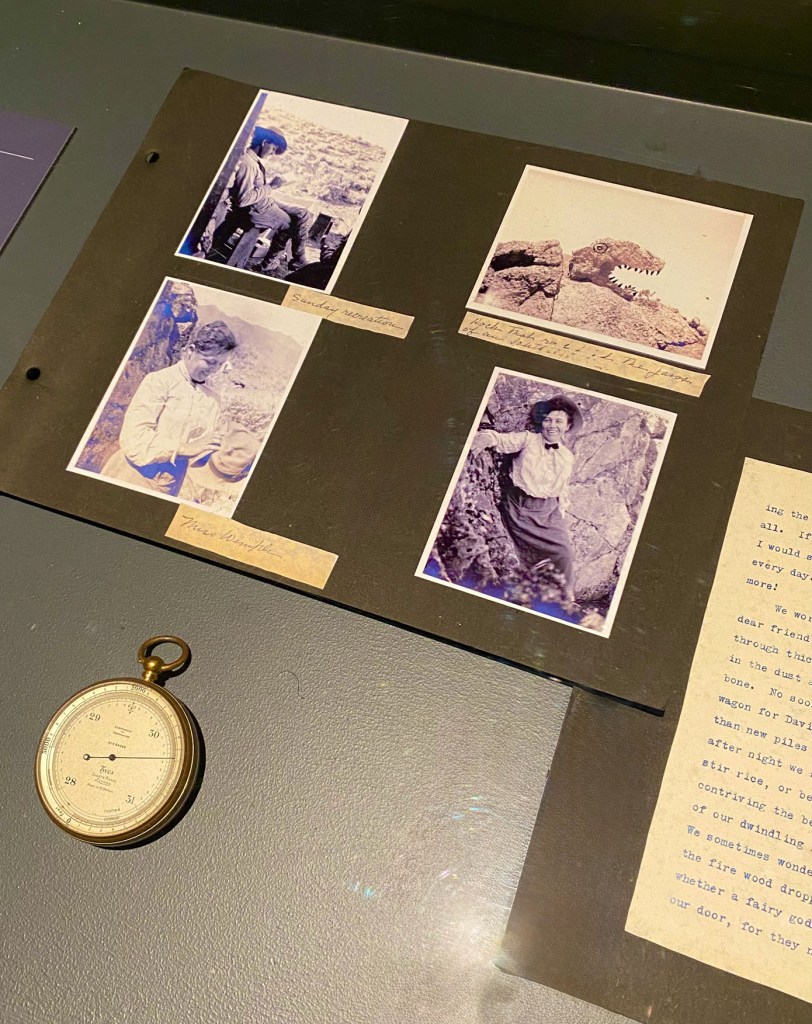

The exhibition space is small, but provides a tight curated selection of Georgia’s things accompanied by great photos of her interiors over time.

The furniture is front and center, made by a who’s who of American 20th century designers. After all, as one of the recognized greats of modern American painting, the designers were often her friends, too. Simple, clean, modern lines – that’s what Georgia liked. But she loved design innovations, too.

No wonder she was captivated by the innovative BFK (“Butterfly”) chair designed by a trio of Argentine architects in 1938. She ordered one from Knoll, used it on her patio, and sometimes took the cover off just to admire the frame. And she bought several LCW chairs by her friends, Charles and Ray Eames – the molded-plywood marvel that defined a design decade.

But perhaps her most-used piece was the versatile BARWA Lounger – perfect for laying back and listening to classical music or looking at the stars during a summer camping trip to the badlands. The aluminum frame made it light enough to strap to the top of her car.

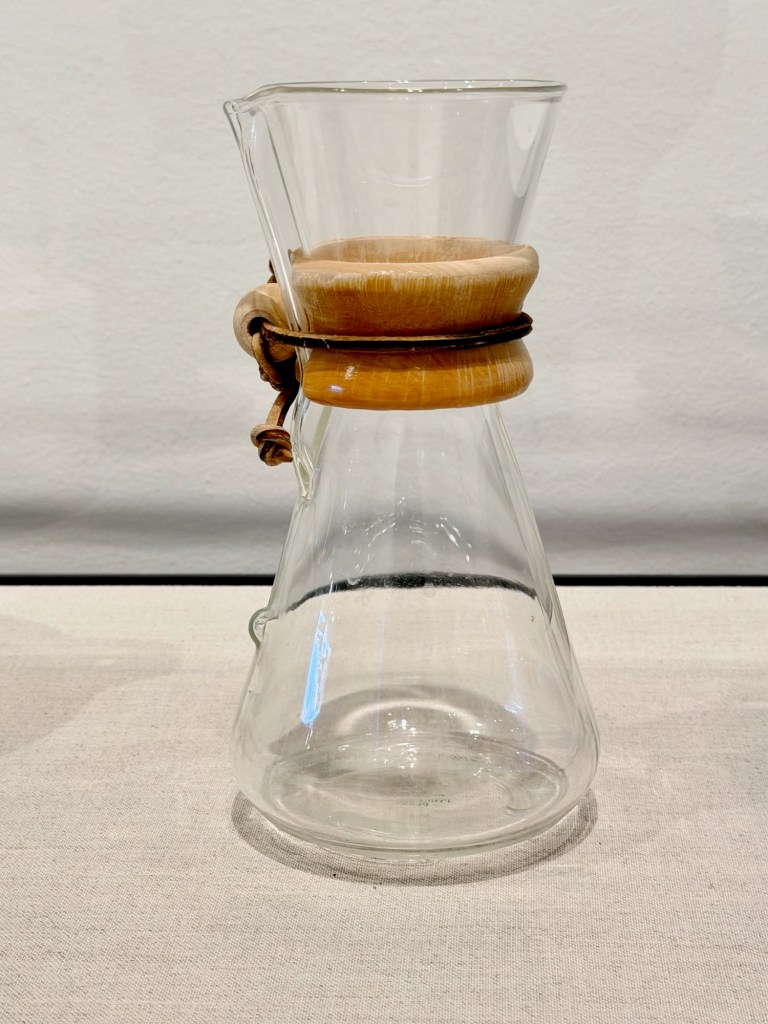

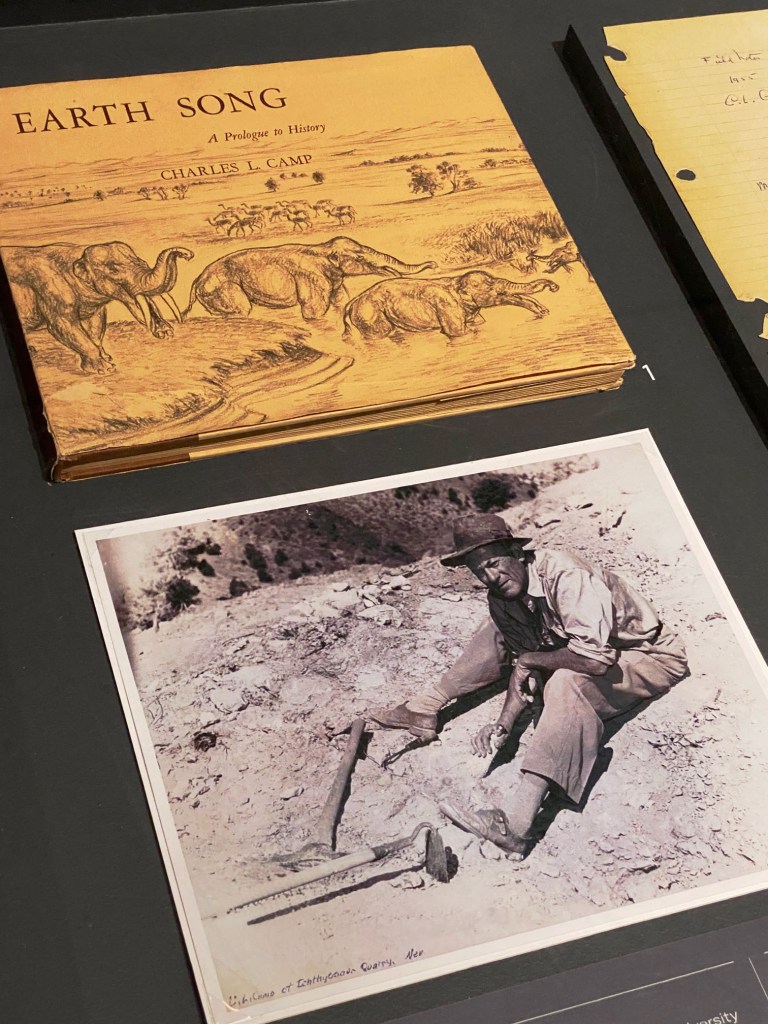

Of course, Georgia loved her rock and bone collections, but she also collected practical items for her home that epitomized mid-century design. Why not select a Finnish design innovation that you could adjust to get the light just right on your work desk or still life? Or use a sleek, modern, see-through coffee maker to prepare your morning cup of Bustelo? Pure bliss.

The curators also want us to remember that modern design principles also extended to Georgia’s dress preferences.

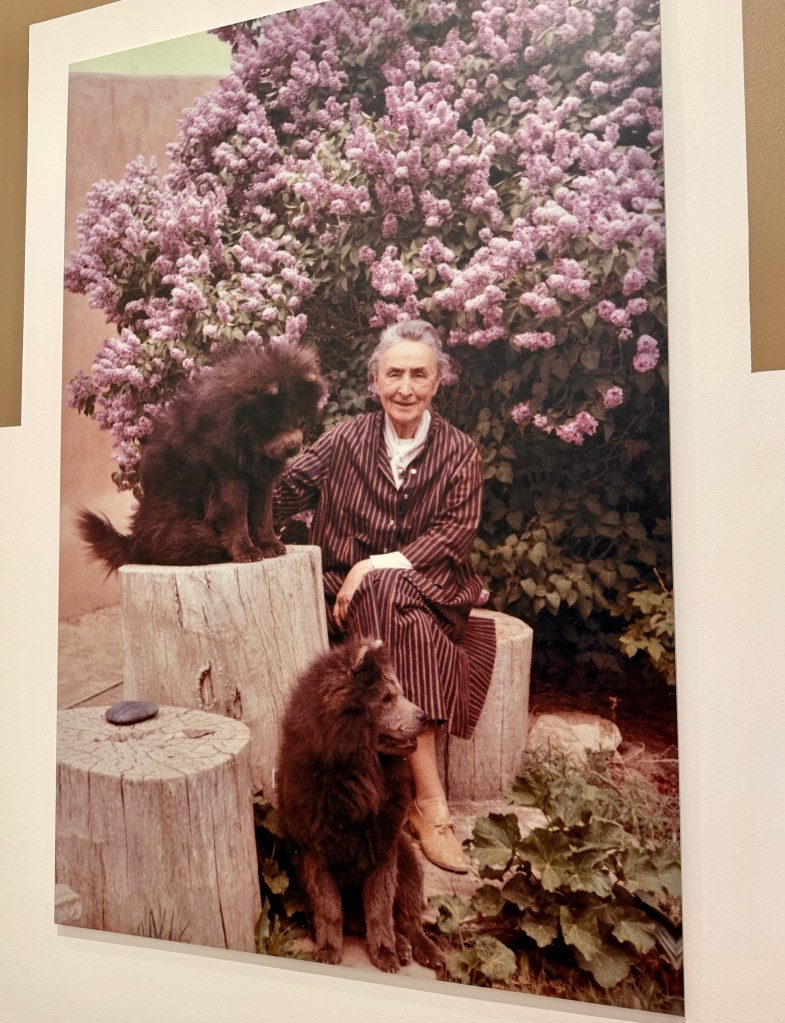

When she wasn’t posing for the most famous photographers against the red rocks of New Mexico in her black hat and wrap dress, she preferred wearing loose-fitting Marimekko dresses. A working studio artist could really move in them to prepare canvases, rehang paintings around the house, or carry around stuff in the pockets. Never mind that the dresses from the popular Finnish design house were marketed as the finishing sartorial touch for any modern Sixties interior.

Feel free to revisit our past blog post about the wildly successful traveling exhibition about Georgia’s fashions here.

See some of our favorite photos, furniture, and items in our Flickr album.

Two of her best friends and travel buddies were Alexander and Susan Girard. Georgia always welcomed the small textiles that Alexander Girard gifted her. Although she never adopted his revolutionary conversation-pit seating, she did get out the sewing notions and turn his iconic designs into small throw pillows placed lovingly (and colorfully) throughout her house. She also covered her kitchen work surfaces in Marimekko oil cloth to make it pop, too.

Visit this fantastic design exhibition on line here, and read more about each of Georgia’s mid-century modern choices.

For more, listen to Giustina Renzoni, the museum’s curator of historic properties, discuss how Georgia turned her modern sensibilities into a legendary high desert home:

And if you’re really interested in what Georgia had in her closet, the next time you’re in New Mexico, sign up for that new extra-special tour!