She grew up on US military bases all over the world, and was thankful that her parents exposed her to the best museums, art, and culture in every country they resided. As an adult member of the Pit River Tribe, she moved back to her ancestors’ land in California and Nevada’s Great Basin, and began telling stories of her family’s history and modern Indigenous experience.

The Art of Judith Lowry showcases 40 years of this artist’s work in Reno, Nevada at the Nevada Museum of Art through November 16, 2025 – large-scale painting, triptychs, and installations.

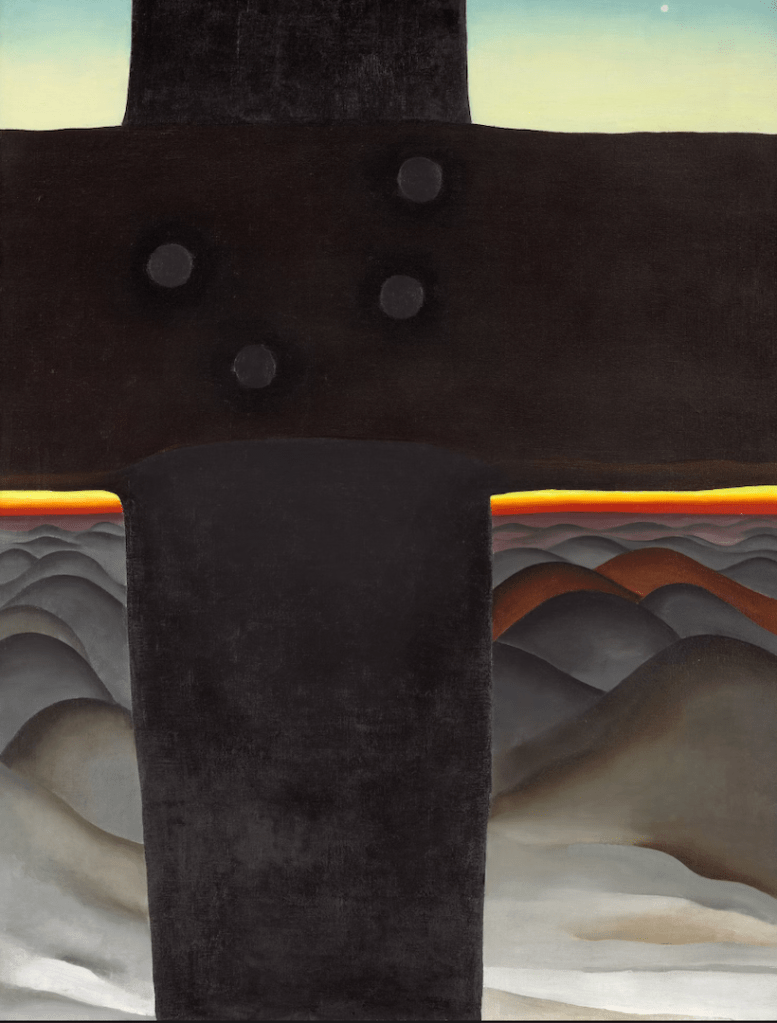

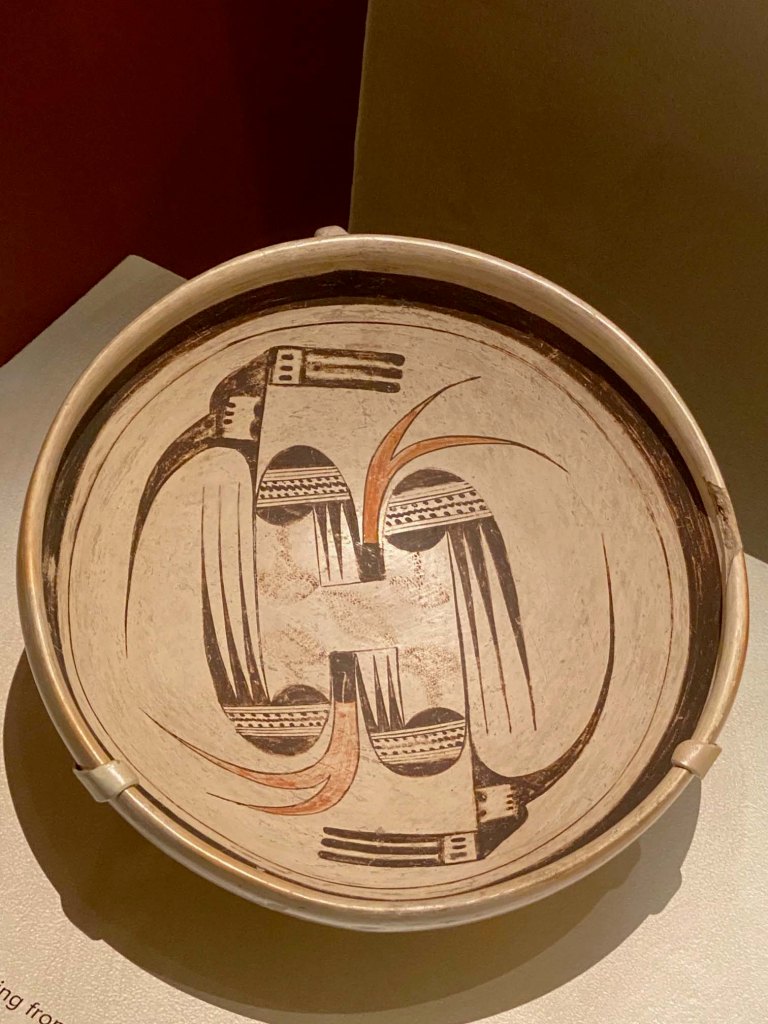

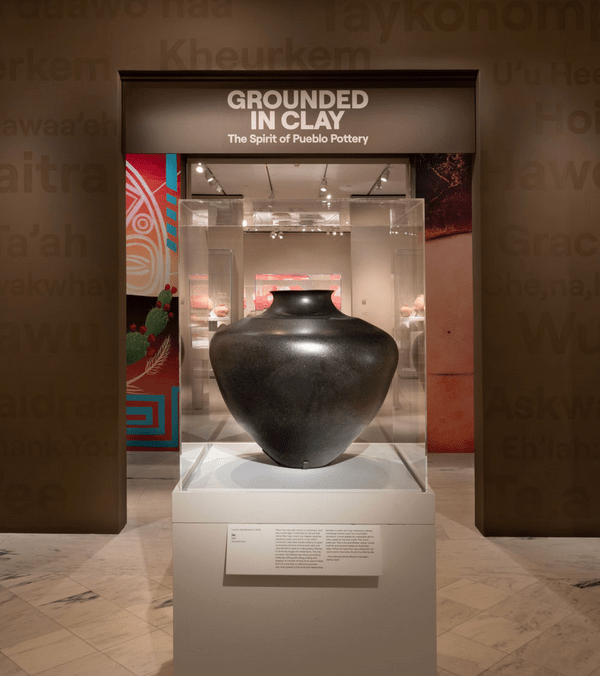

The museum assembled Lowry’s most celebrated work from major collections across the United States, but is also using the occasion to celebrate Lowry’s own (and her husband’s) gift to the museum with a companion installation of The Lowrey and Croul Collection of Native American Art.

Take a look at some at our favorites from both shows in our Flickr album.

The entry of the exhibition shows how Lowry explores her complex family history at the turn of the last century in frontier ranch lands along the California-Nevada border – images of her biracial great-grandparents and a beautifully mystical depiction of her grandmother. Her regal portrait shows her ancestor’s face tatoos coupled with perfect Victorian dress and small references to the tragedies that befell her family – a symbolic approach Lowry adapted from her deep appreciation of Renaissance works by Bellini, da Vinci, and other masters.

A case in the center of the gallery presents Lowry’s paintings for her children’s book about her father and uncle’s Indian boarding-school experience, break out, and unauthorized journey back home.

She also presents family photos and representations of her own growing-up with rich stories and excerpts from her family photo albums. The experience of reading personal history, seeing her ancestors’ faces, and looking at the painted details on her epic canvases is a deep, warm experience that allows you to feel like you’re welcomed into Lowry’s complex and loving family.

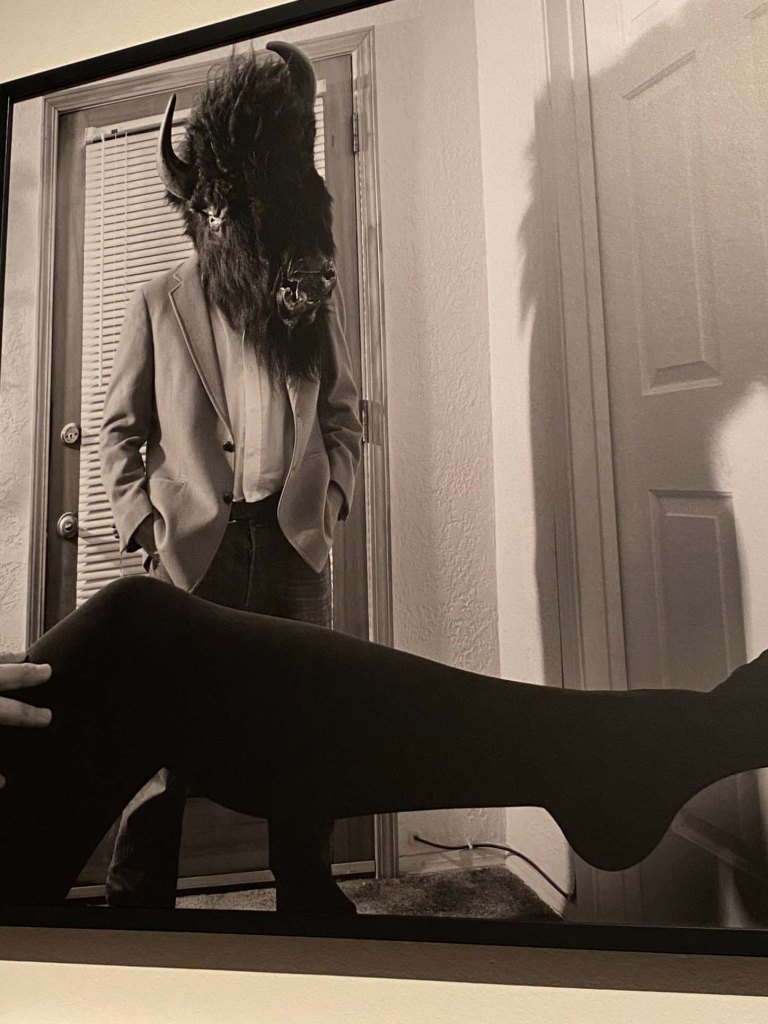

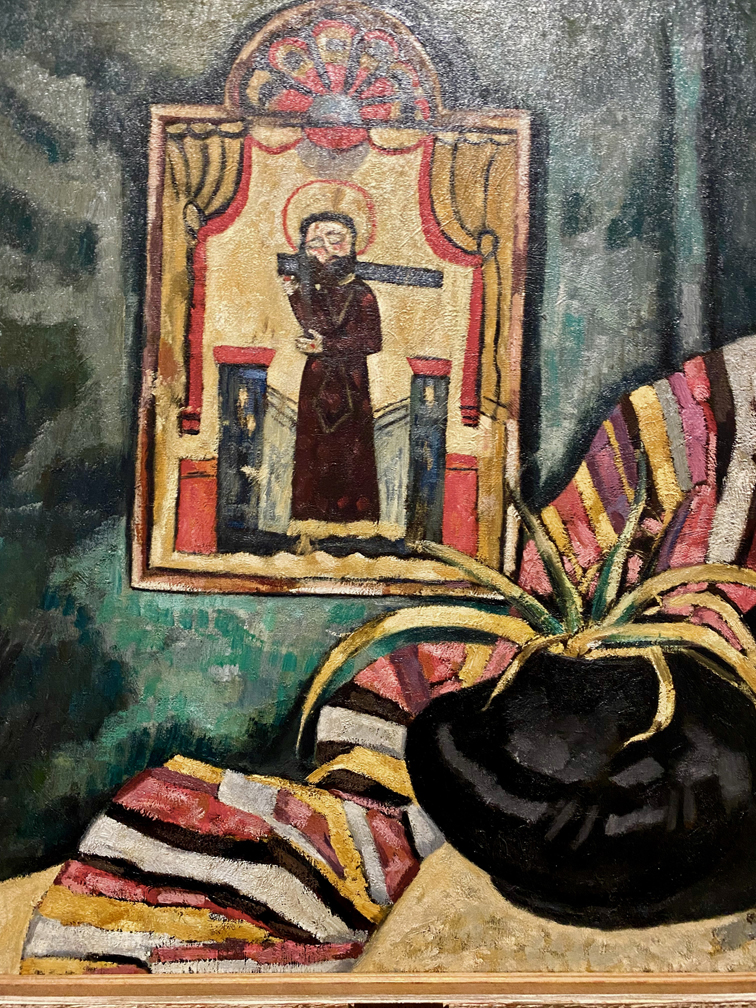

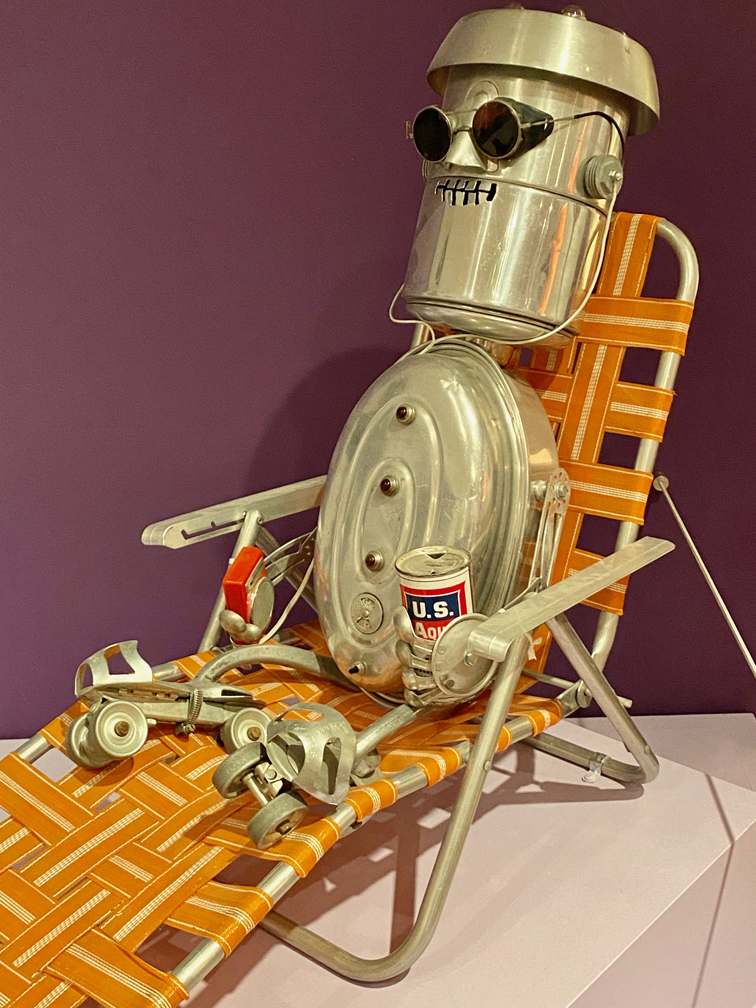

Many of the paintings are satiric takes on the pressures facing contemporary Native Americans navigating life in modern American society – startling theatrical juxtapositions in Indian casinos, retail emporiums, and Renaissance altarpieces.

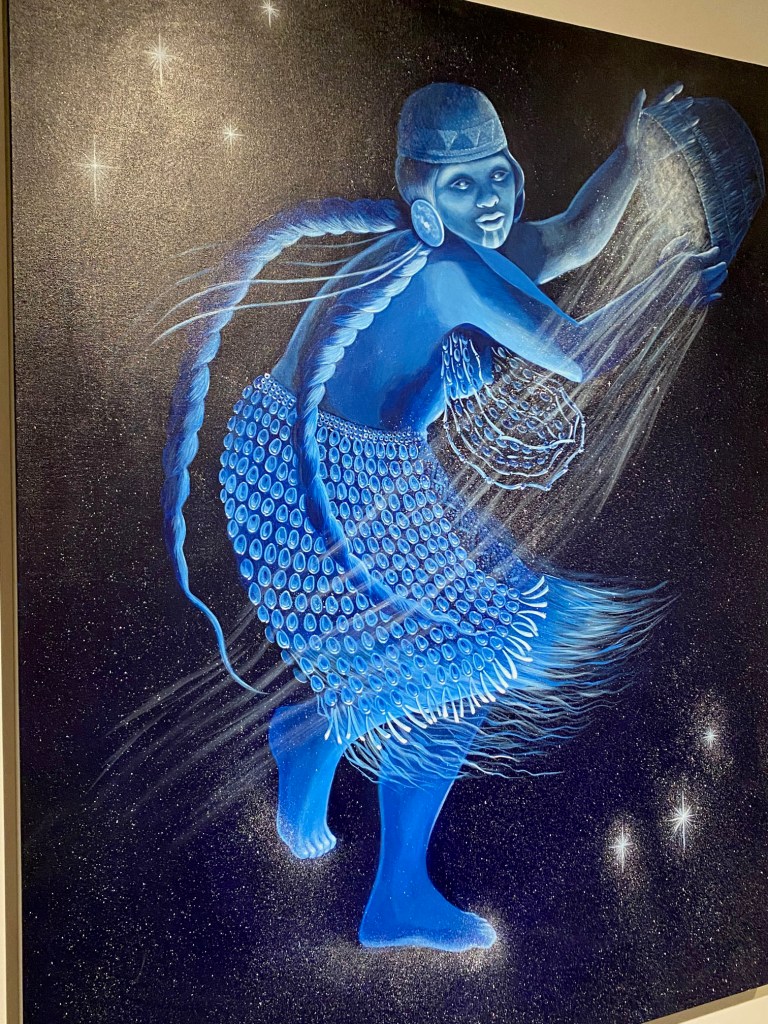

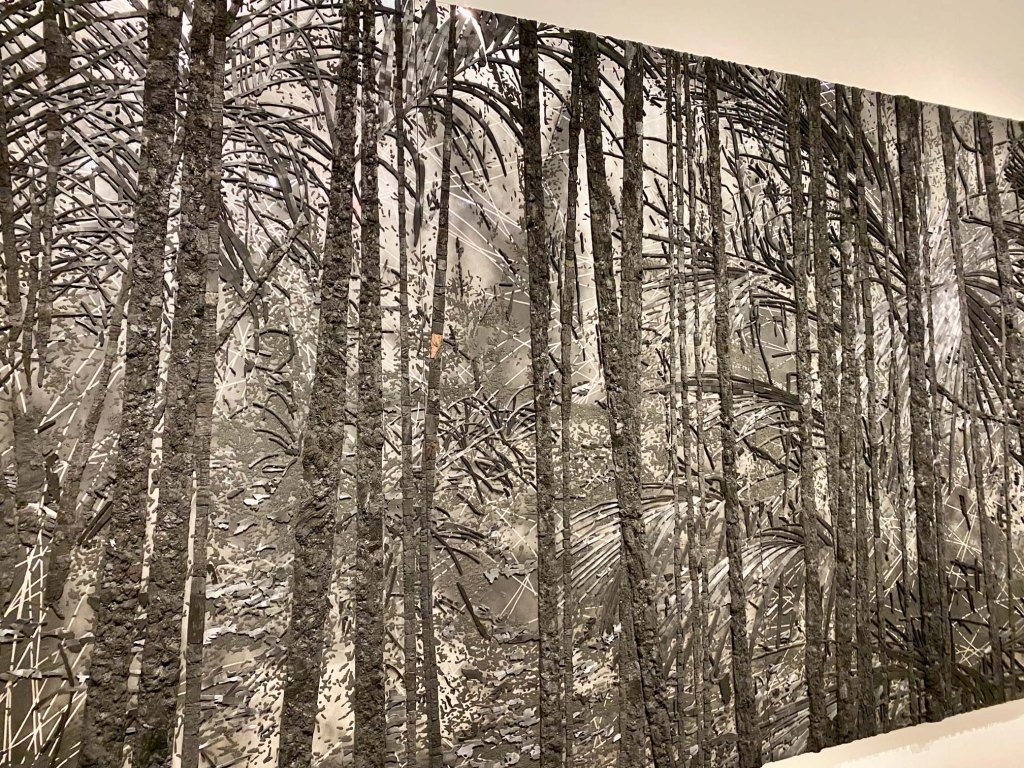

Some of the most arresting works allow us to enter a spiritual realm – magical depictions of legends, stories, and lessons that she heard from her dad growing up. Lowry’s large-scale, dramatic canvases are immersive – letting us enter the world of the girl-power Star Maidens, who who dance across the sky holding baskets of stars and tossing comets.

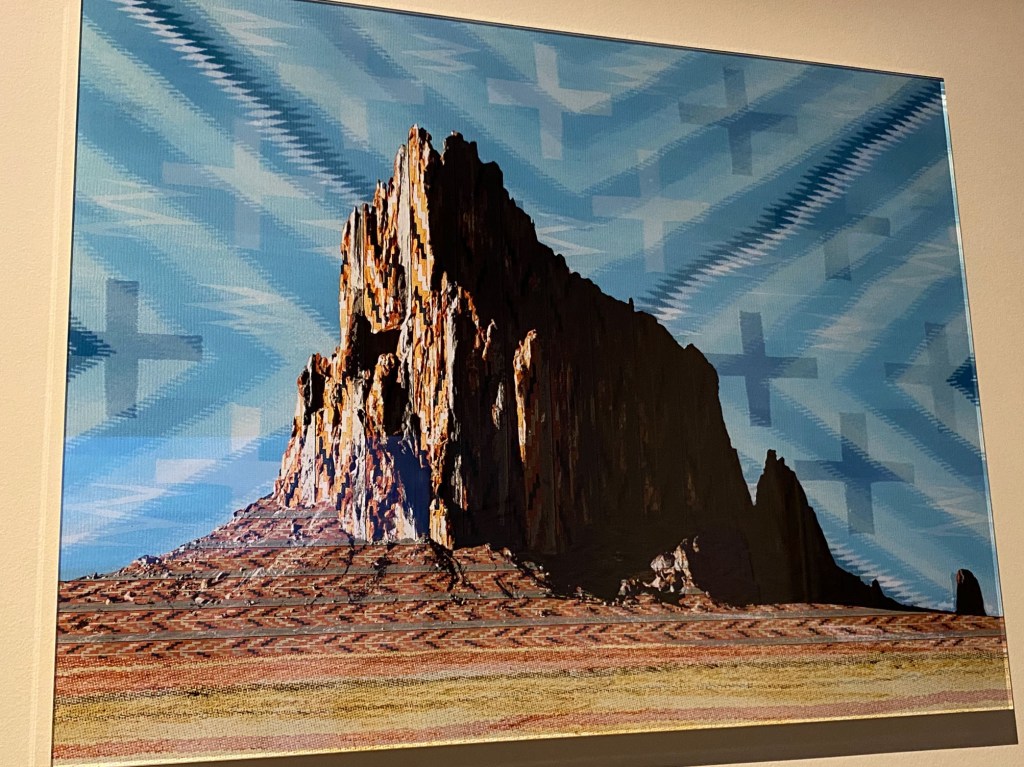

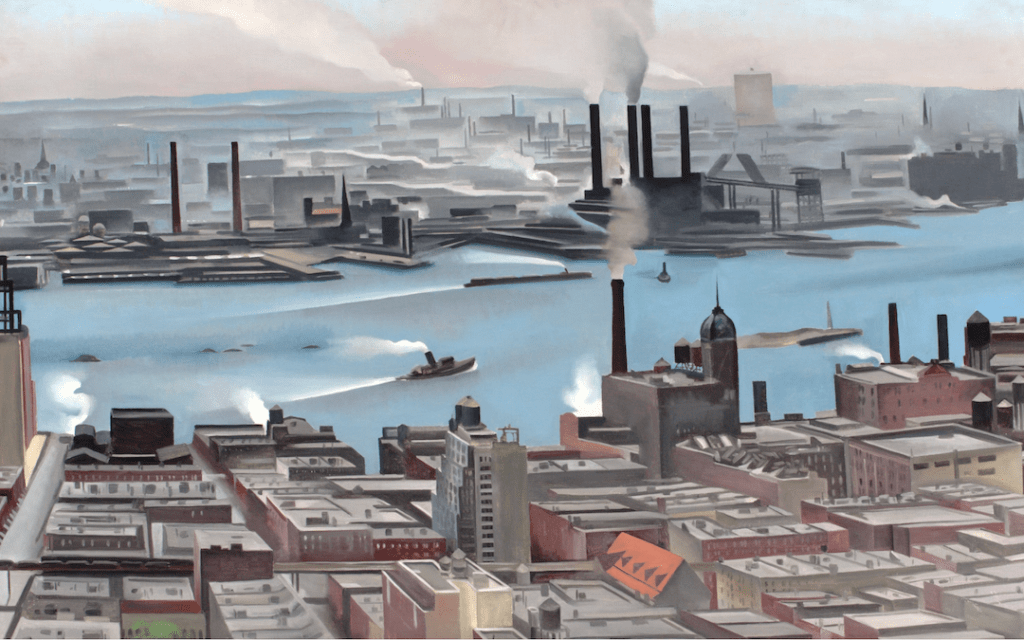

Or letting us enjoy the epic, triumphant forces of natural world that led to the environment Lowry now inhabits in the shadow of the Sierra Nevadas.

But at the end of her retrospective, Lowry presents the ultimate immersive experience – an imagined native Northern California roundhouse where visitors can enter, think, and see mystical images of Lowry’s inspiring female ancestors, tribal story-carriers, and cultural symbols. Visitors enter quietly and linger respectfully, taking in all the details of the painted walls and dome. See our short video to see Lowry’s comforting interior.

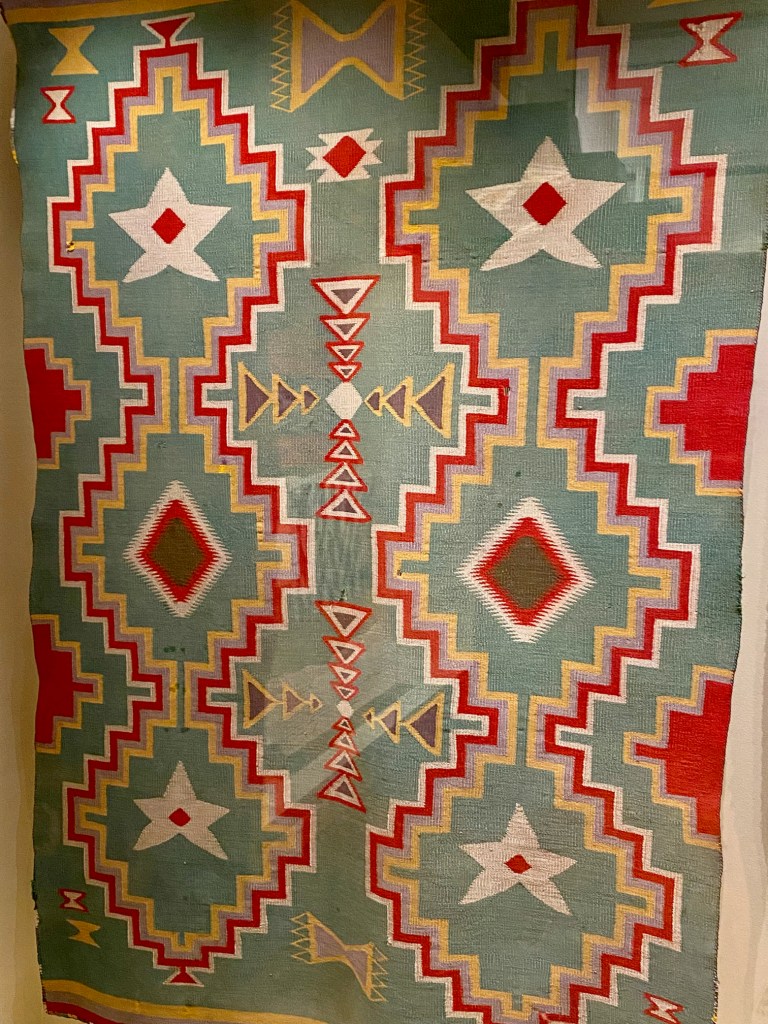

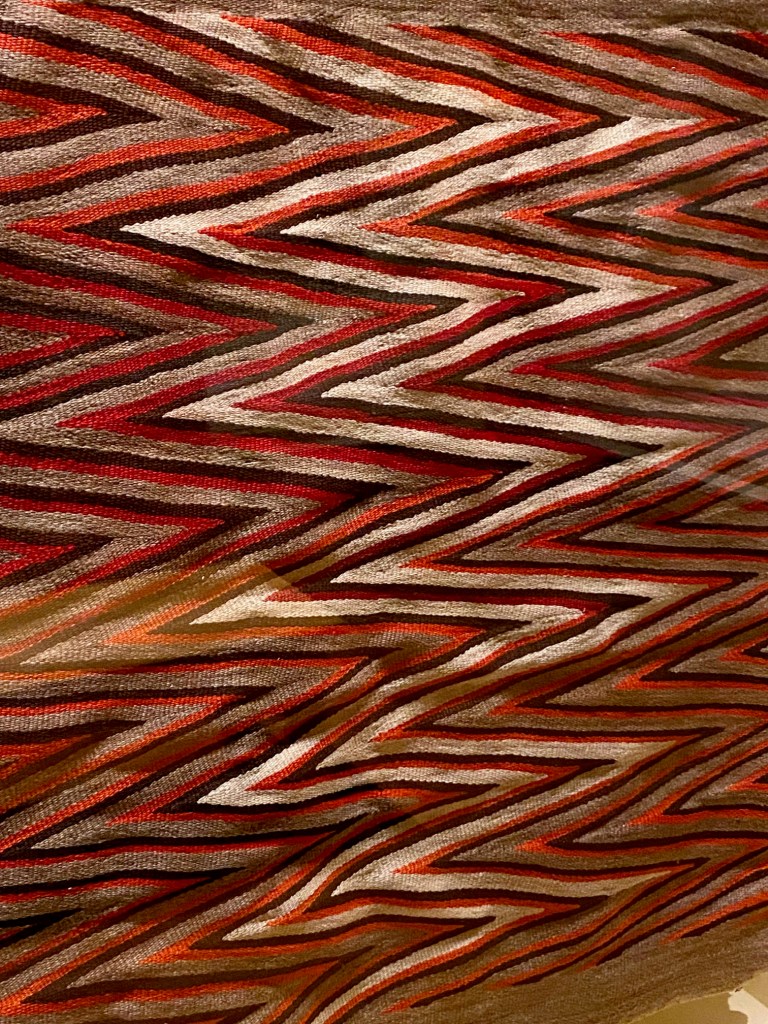

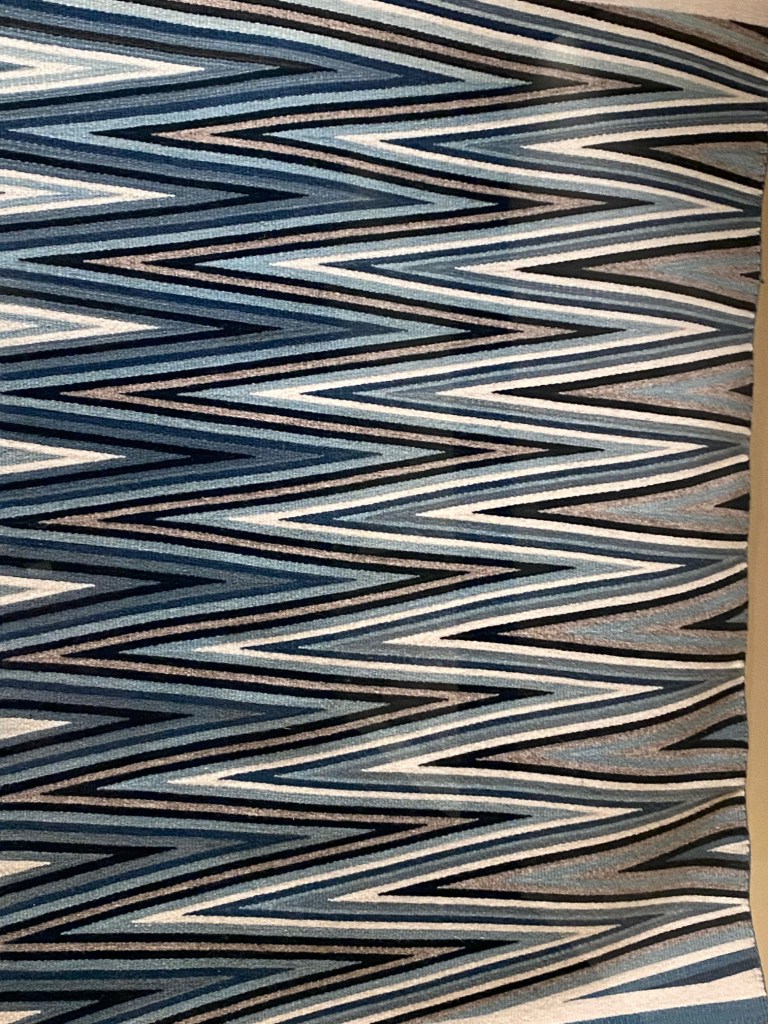

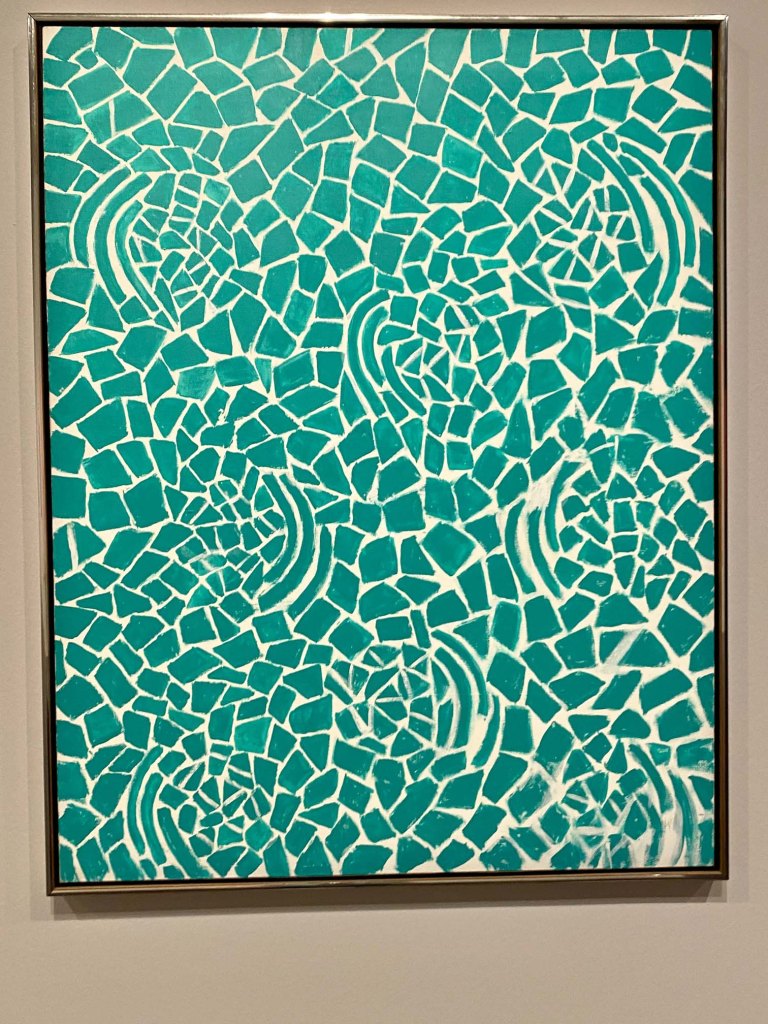

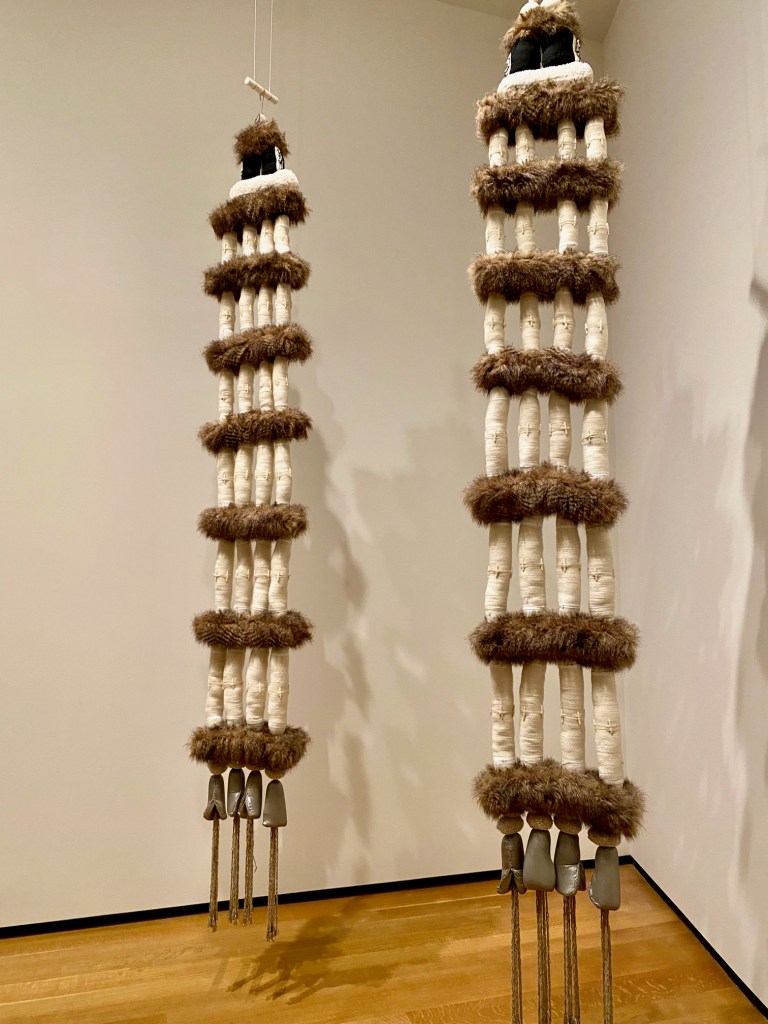

After immersion in this spiritual space, visitors enter a bright contemporary gallery displaying some of the 125 contemporary Indigenous works that Lowry and her husband Brad Croul donated to the Nevada Museum – honoring the accomplishments of the notable artists working in the region in the 1990s. The gallery is filled with art by famed Northern California indigenous artists (inspirations and friends like Harry Fonseca and Jean LeMarr. The gift significantly expands the museum’s indigenous contemporary collection.

It’s also a nice punctuation that the spectacular case of beaded glasswork by Lorena Gorbet also features a treasured piece of Judith’s family history – a beautiful grasshopper-stitch basket made by Judith’s great-aunt Annie Gorbet when she was only fourteen years old.

Lowry’s work and generous collection provide a loving immersion into family, friends, and spiritual traditions of the Great Basin. It’s a rich tribute to a prolific contemporary artist – one who cares about her culture and committed to ensuring its legacy for her region.