Any visitor to Chaco Canyon National Historial Park (850-1250 CE) makes the journey to appreciate innovative masonry of the Great Houses, the precision of the ancient road system, and the astronomically aligned walls, windows, and kivas. But how do contemporary Pueblo architects incorporate these traditional beliefs in their 21st century projects?

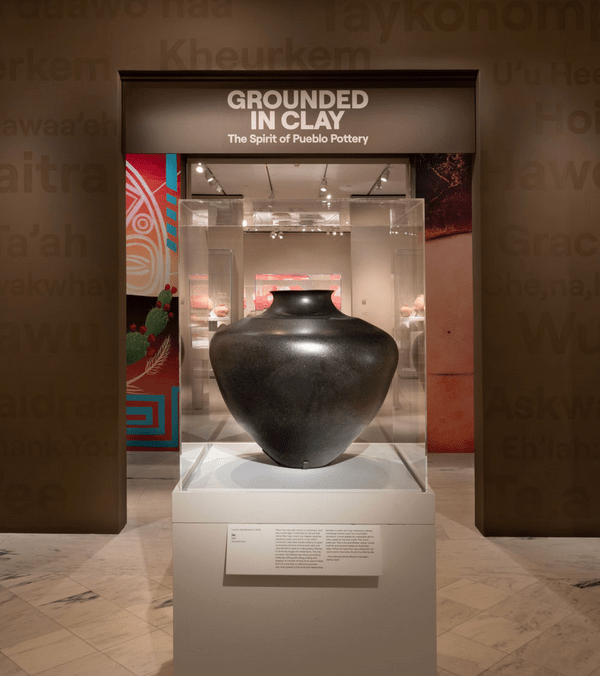

A fascinating, in-depth exhibition, Restorying our Heartplaces: Contemporary Pueblo Architecture – on view at Albuquerque’s Indian Pueblo Cultural Center through December 7, 2025 – explores how modern Indigenous architects incorporate traditional world views into their work.

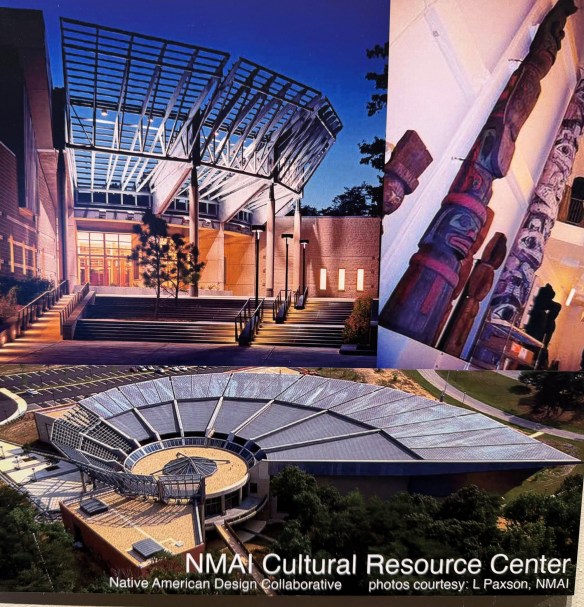

For example, just look at the design of the National Museum of the American Indian’s Resource Center – an organic design, aligned to the four cardinal directions, with extensive use of cedar wood.

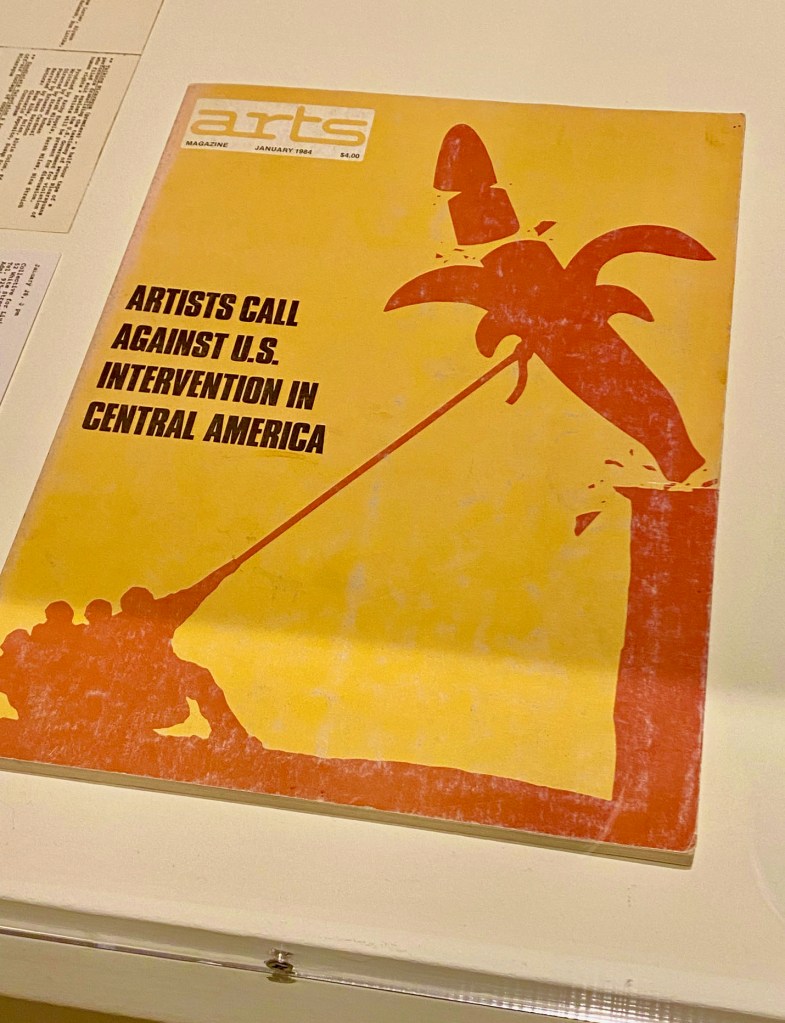

This exhibition coincides with the 50th anniversary of the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act – legislation that shifted Native American policy in the United States from assimilation to self-determination. Tribes were now able to initiate and run justice, government, health and education departments of their own – a change that triggered a construction boom for new schools and administrative buildings.

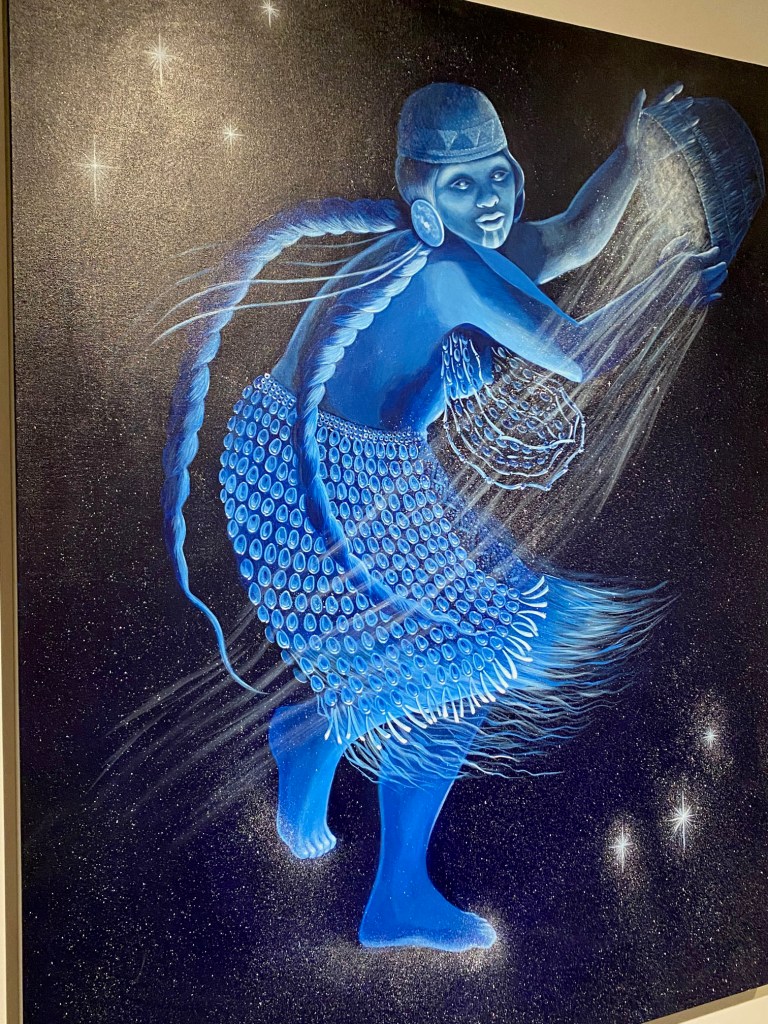

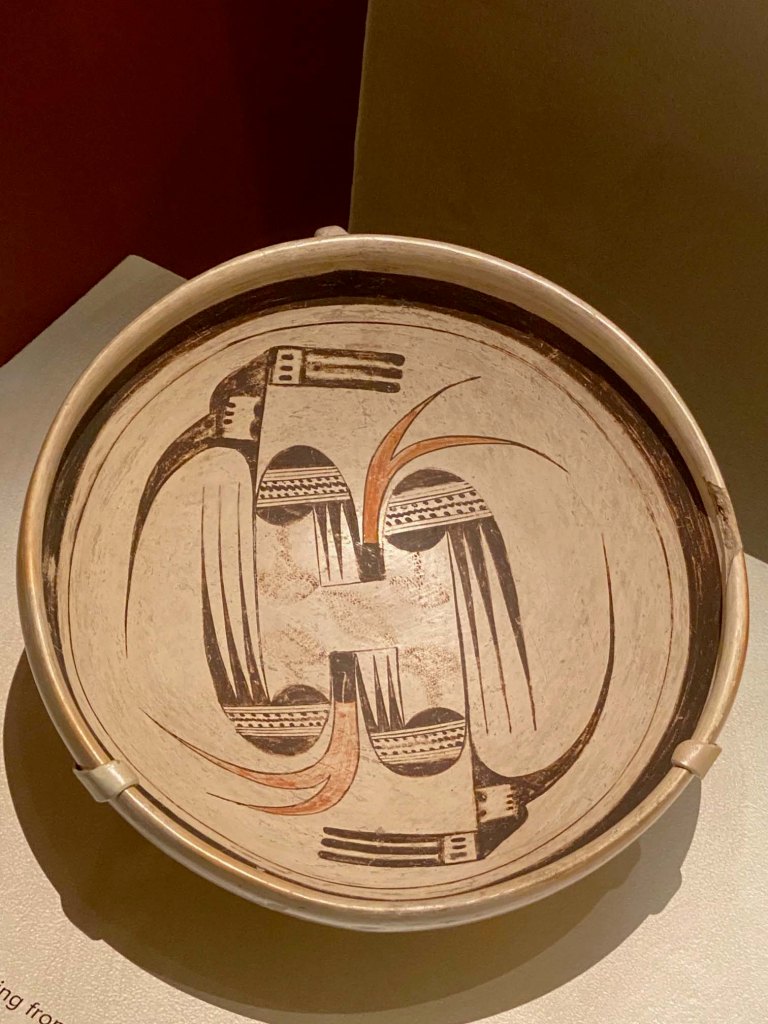

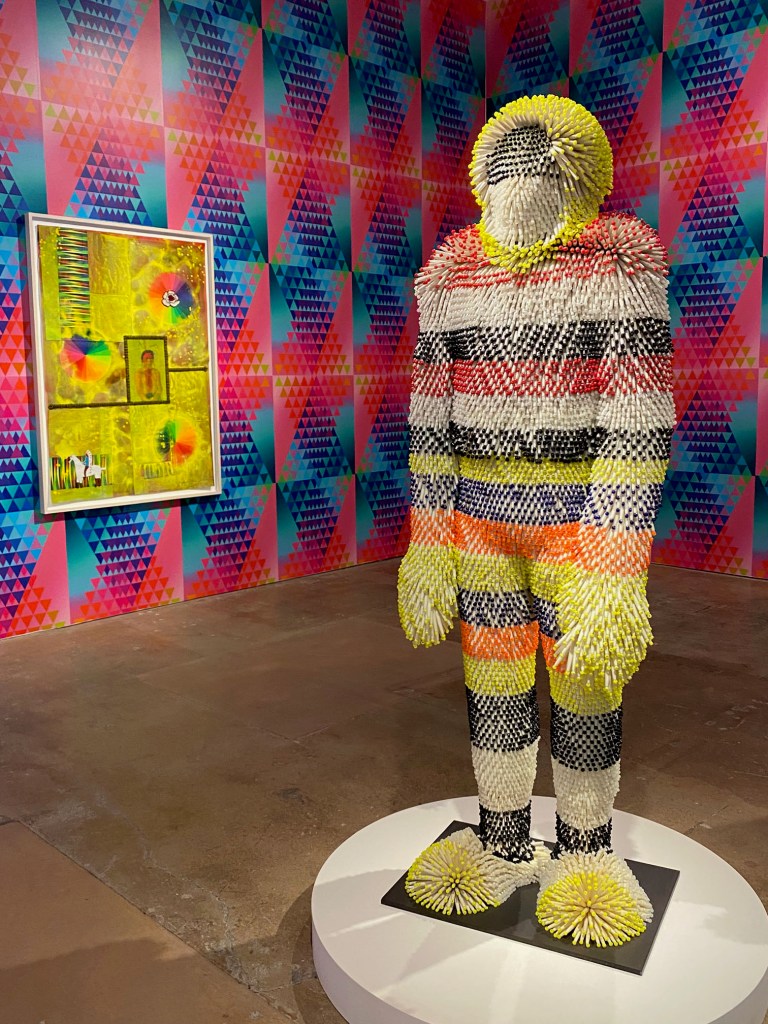

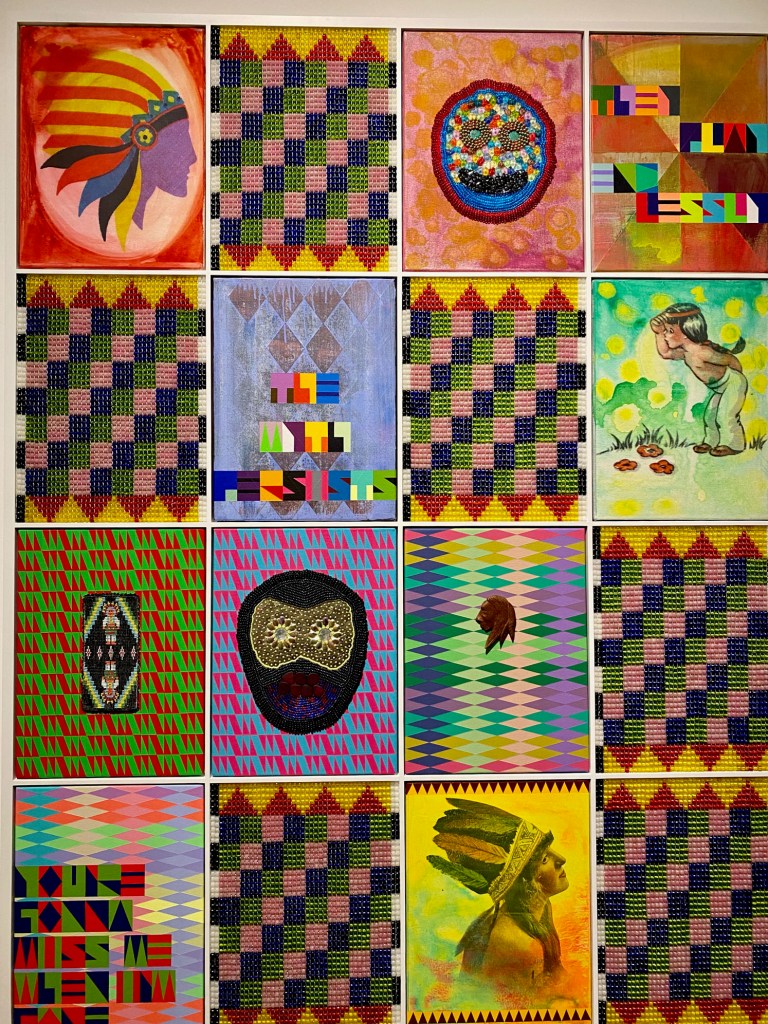

The show opens as an immersive experience in a large, circular gallery that introduces the core belief system and origin story of the Ancient Puebloans. Across a large screen in a vivid animation, the Pueblo people emerge into this world from a previous world. You watch them migrating outward in a spiral – symbols that are reflected across the art, murals, and photographs on the surrounding walls.

This experience sets the stage for the rest of the exhibition by showing how the stonework and beliefs reflected by the architecture of Ancient Puebloan centers points the way forward for Pueblo architects today.

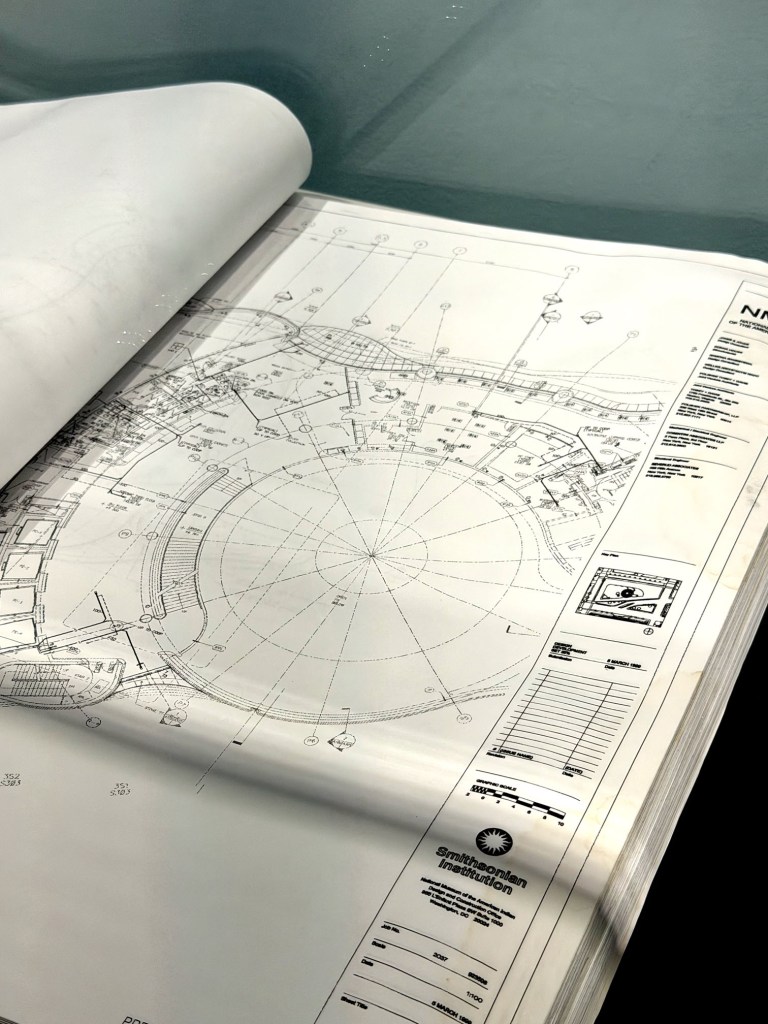

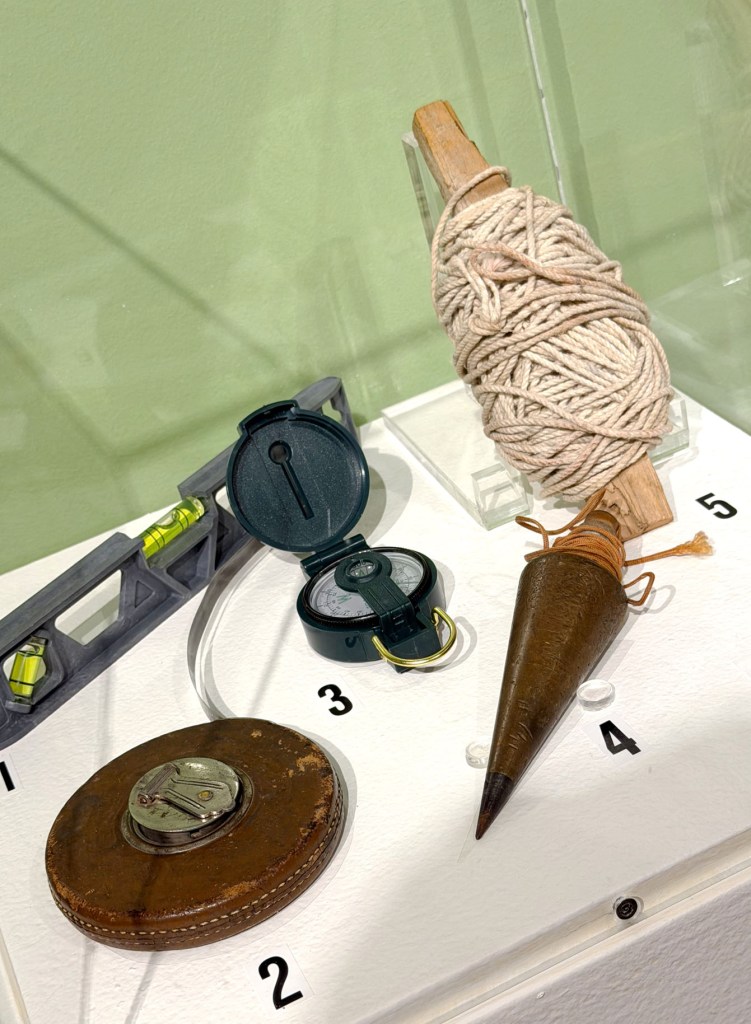

The exhibition describes Ancient Puebloan architectural innovations – passive solar heating, precise window alignment, and masonry approaches. How did the Ancients achieve such precision in their dramatic Chaco and Mesa Verde buildings?

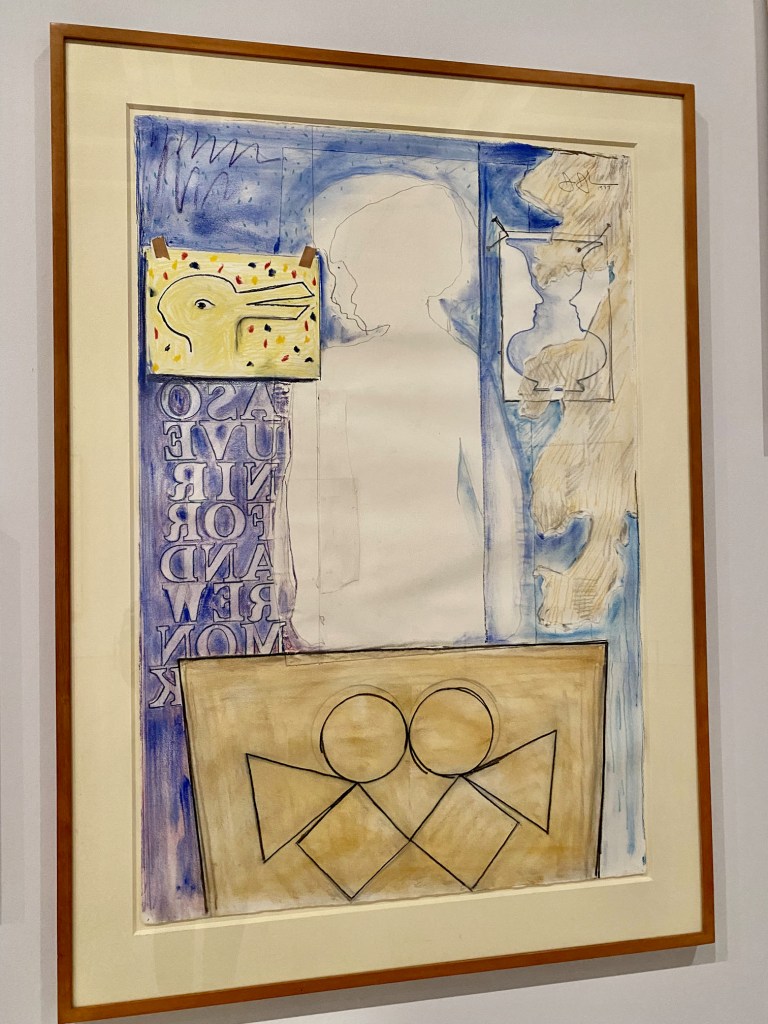

The curators present engineering and survey tools from archaeological excavations and modern survey backpacks side by side – plumb bobs, levels, and measuring devices.

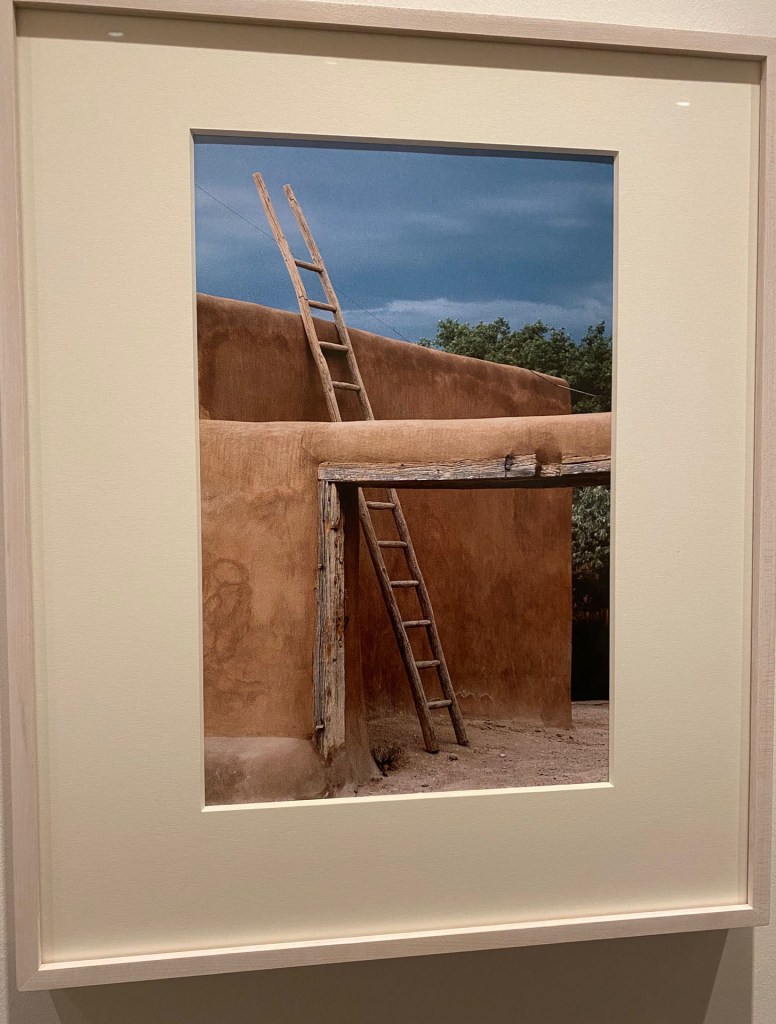

They also add comparisons of selenite used as window panels in Old Acoma’s Sky City (among the longest-inhabited communities in the US) and the contemporary architectural approach to windows in the recently built Acoma museum – a thoughtful reflection of the past

The exhibition directly addresses past HUD housing approaches on tribal lands – pushing suburban-style low-income housing, which moved families away from the traditional Pueblo plaza (the HeartPlace) and provided pitched-roof designs that blunted community cultural practices that utilized traditional Pueblo flat-roof construction.

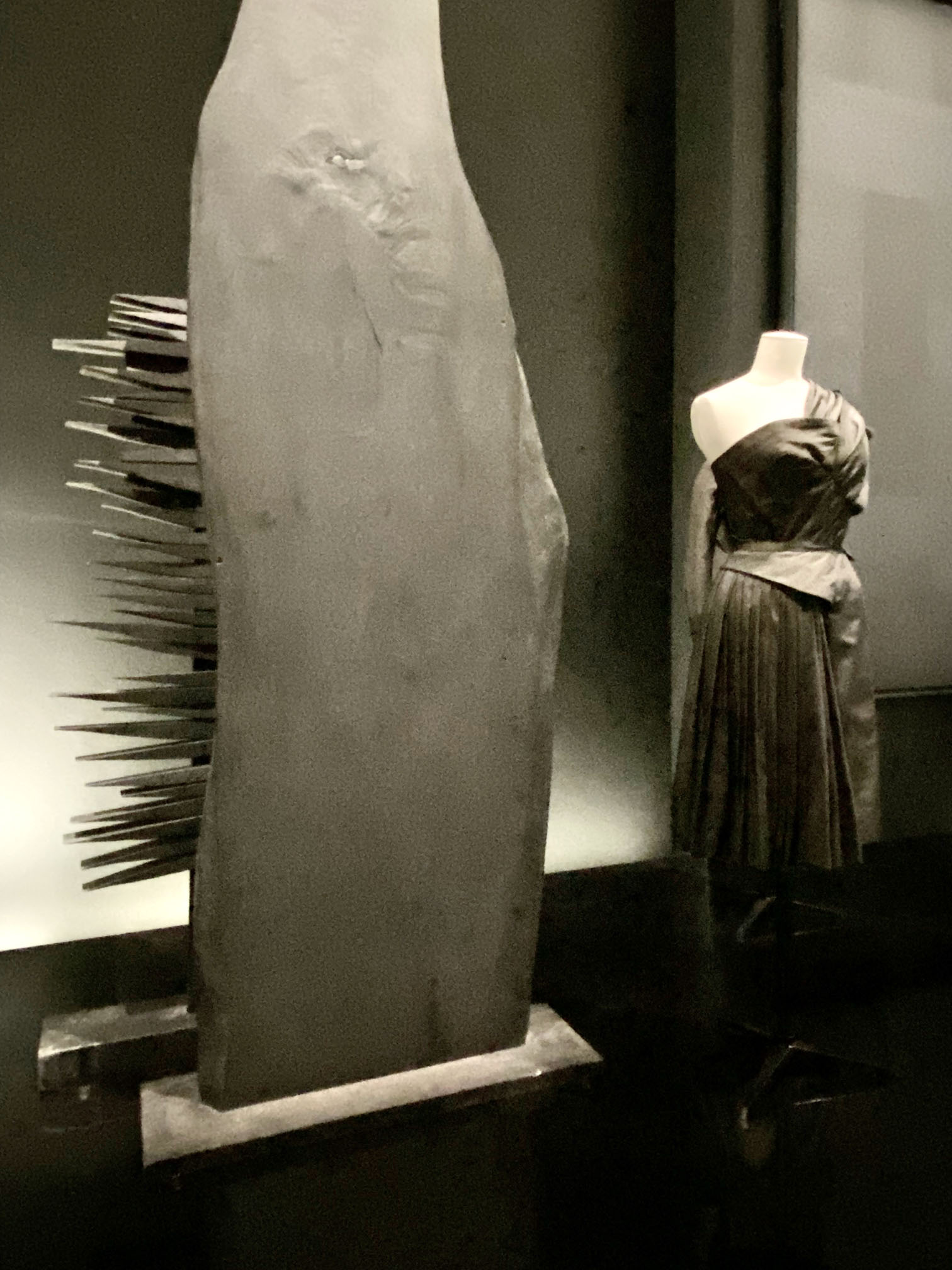

The curators remind us of the continual upkeep required by adobe construction – a repeated communal task typically undertaken by a community’s women that happened on a regular, cyclical basis. It’s also a reminder that Pueblo communities view buildings as living presences that evolve – not just concrete objects exist in a “finished” state.

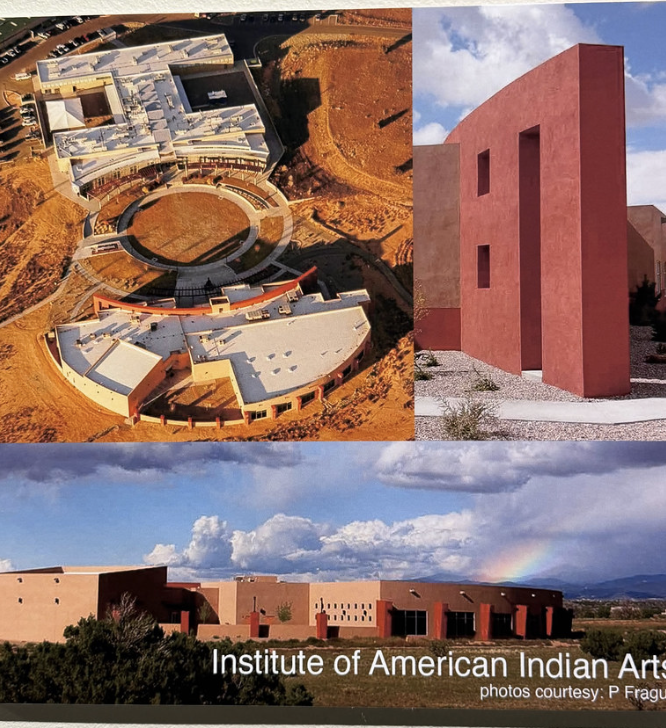

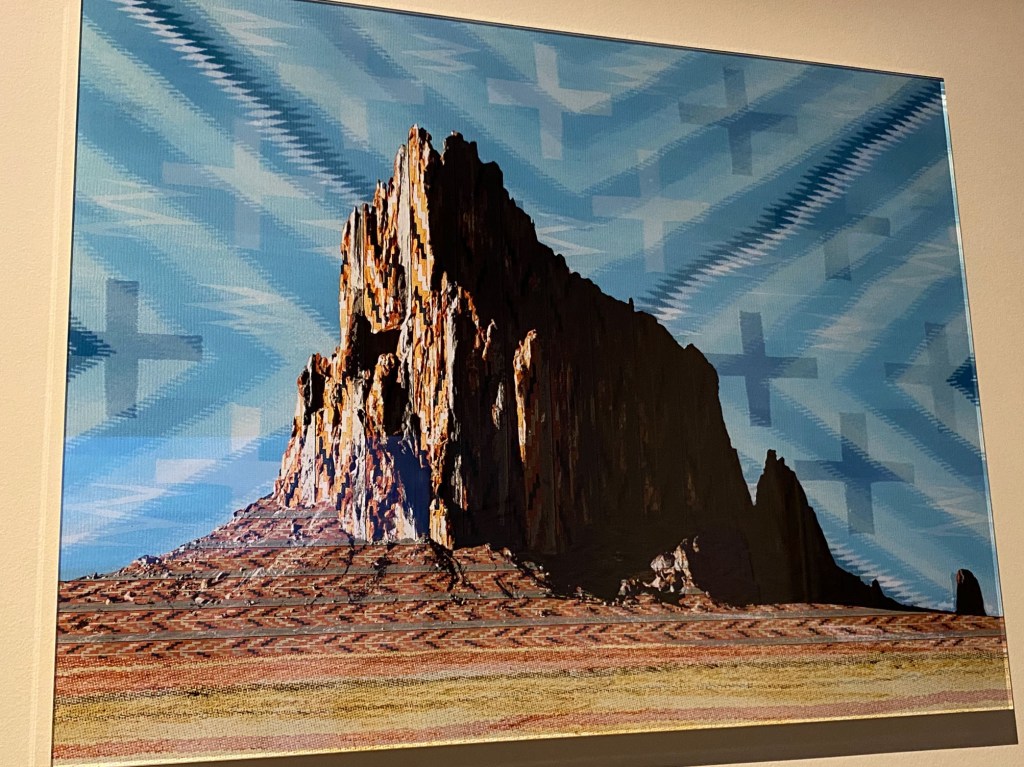

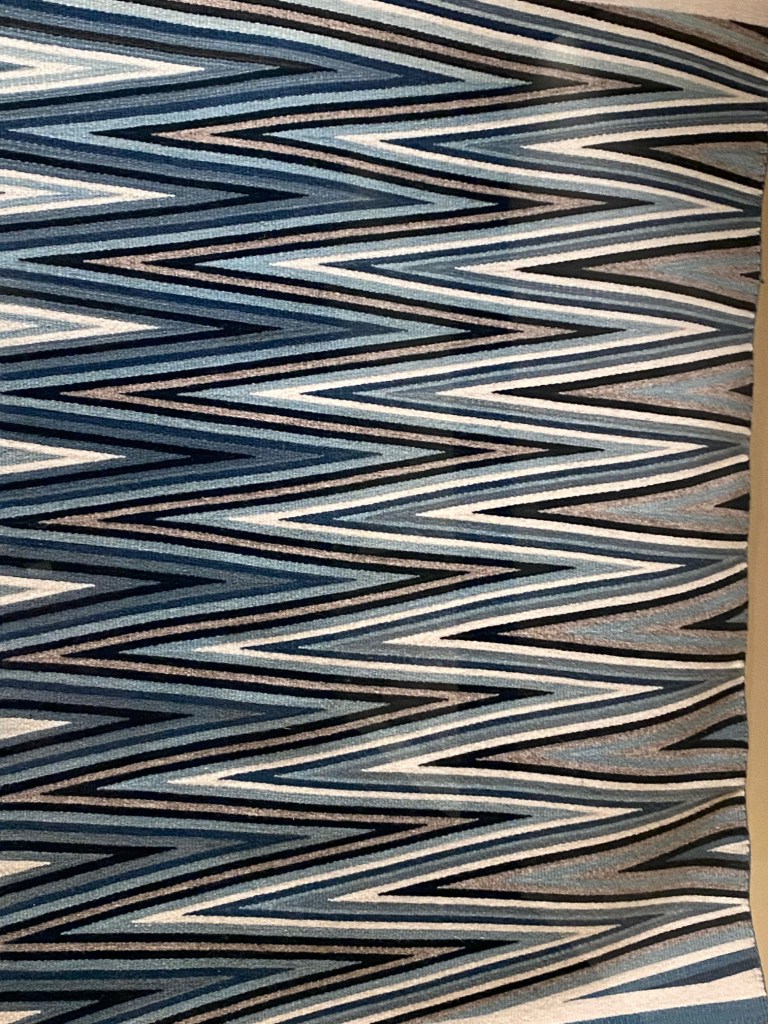

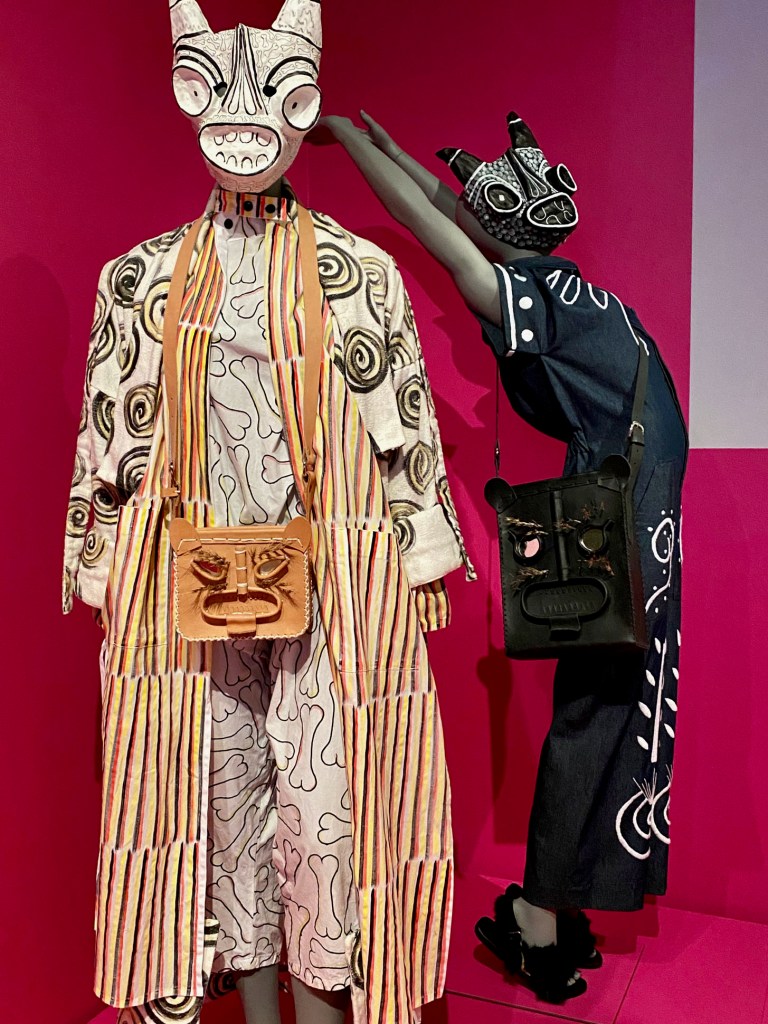

Wall panels, blueprint books, and architectural models are used to demonstrate the contemporary innovations of Pueblo architects – the Resource Center of the National Museum of the American Indian (1999), the campus of the Institute of Amercian Indian Arts in Santa Fe (2000), and the Headstart Child Care Center for Isleta Pueblo (2004). Both incorporate design elements echoing the spiral migration path, alignment to the cardinal directions, and colors and elements of the Earth.

A huge multimedia interactive theater punctuates the walk-through – an immersive visit to Acoma’s new Cultural Center and Haa’ku Museum with tribal members and designers explaining the architectural details and how the buildings reflect the landscape and traditional belief systems.

The exhibition features the work of the Indiginous Design and Planning Institute (iD+Pi) at UNM and presents dramatic architectural models of the past, present, and future of the community of Nambe Pueblo.

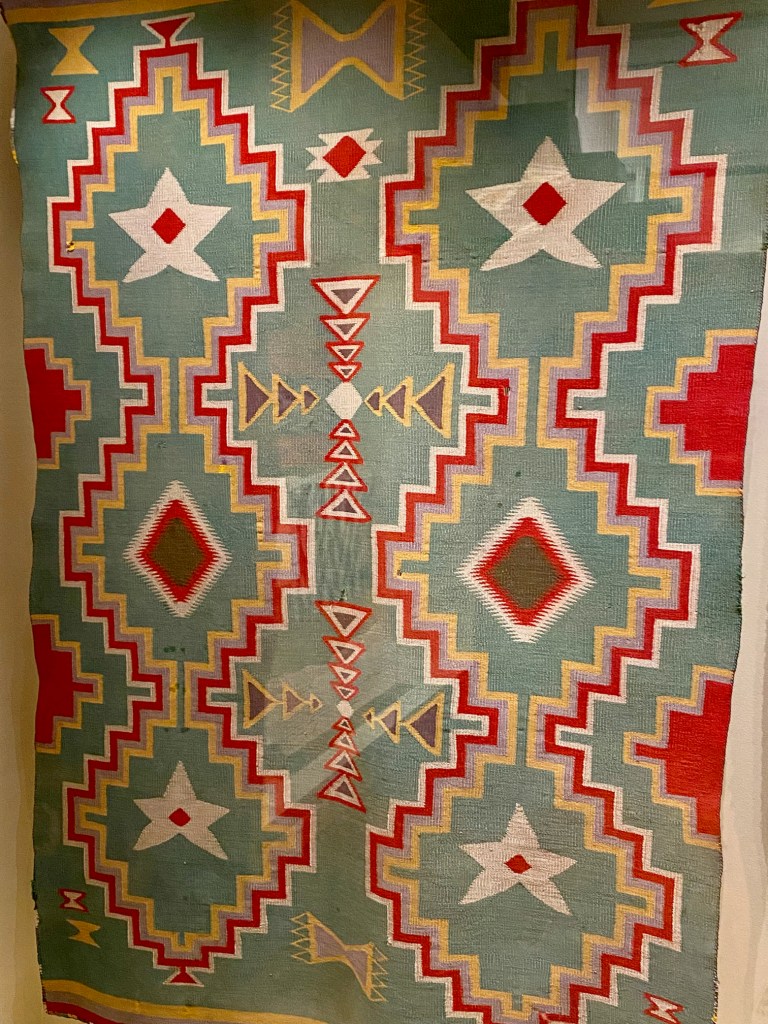

Look through the exhibition in our Flickr album here – a future-forward look at the continuing progression of innovative architectural designs and the next generation of designers and architects respecting and integrating the Pueblo world view with buildings considered to be living, breathing HeartPlaces for the community.

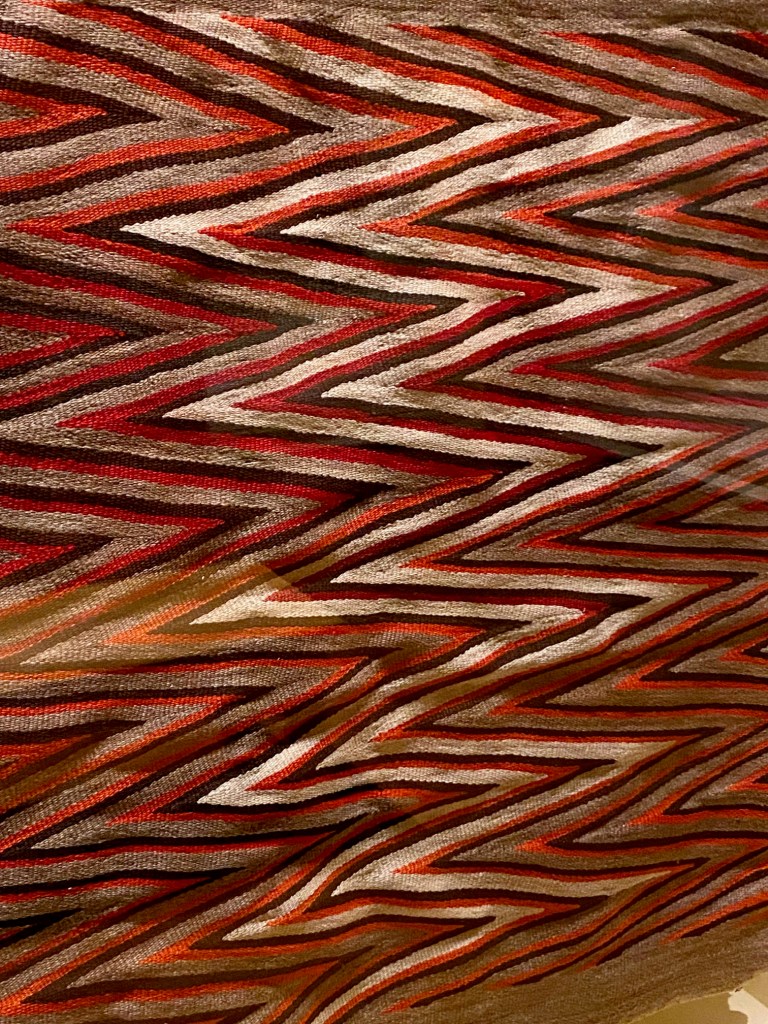

As the curators made clear in their opening-day remarks, a similarly extensive exhibition could explore architectural innovation and spiritualism across Navajo Nation. Let’s hope that happens!