It’s fitting that Kerry James Marshall provides a master class in history painting at the Royal Academy of Arts in London – one of the most sensational shows to inhabit those hallowed galleries off Picadilly – Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, on view through January 18, 2026.

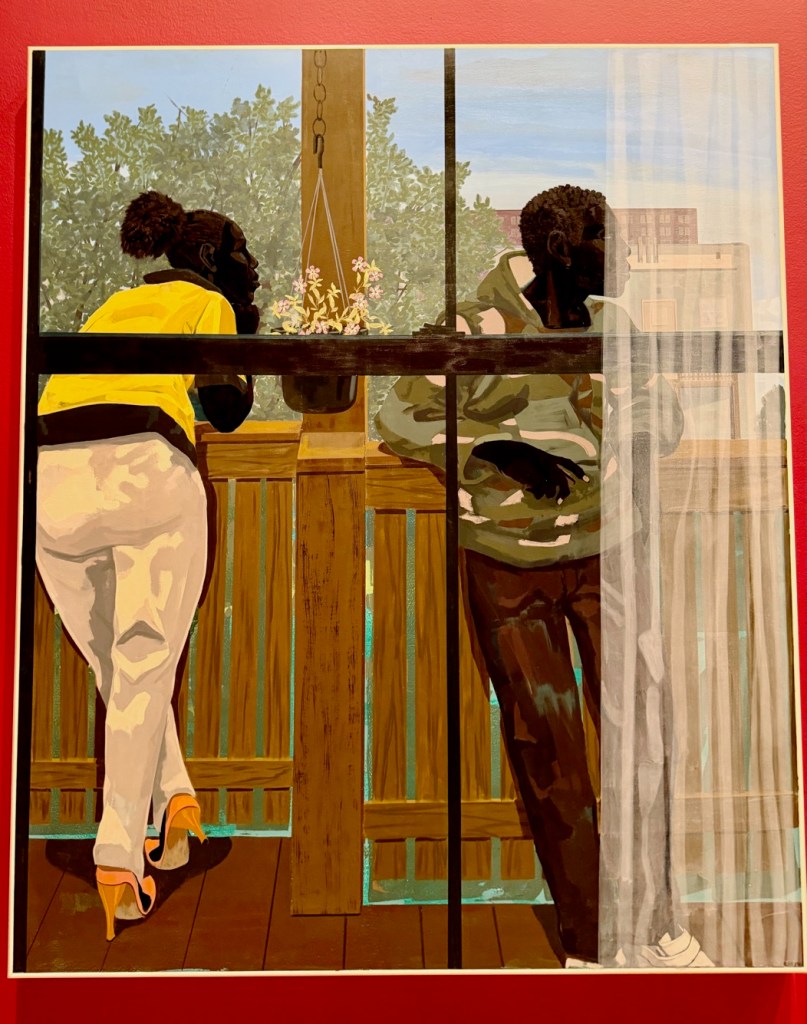

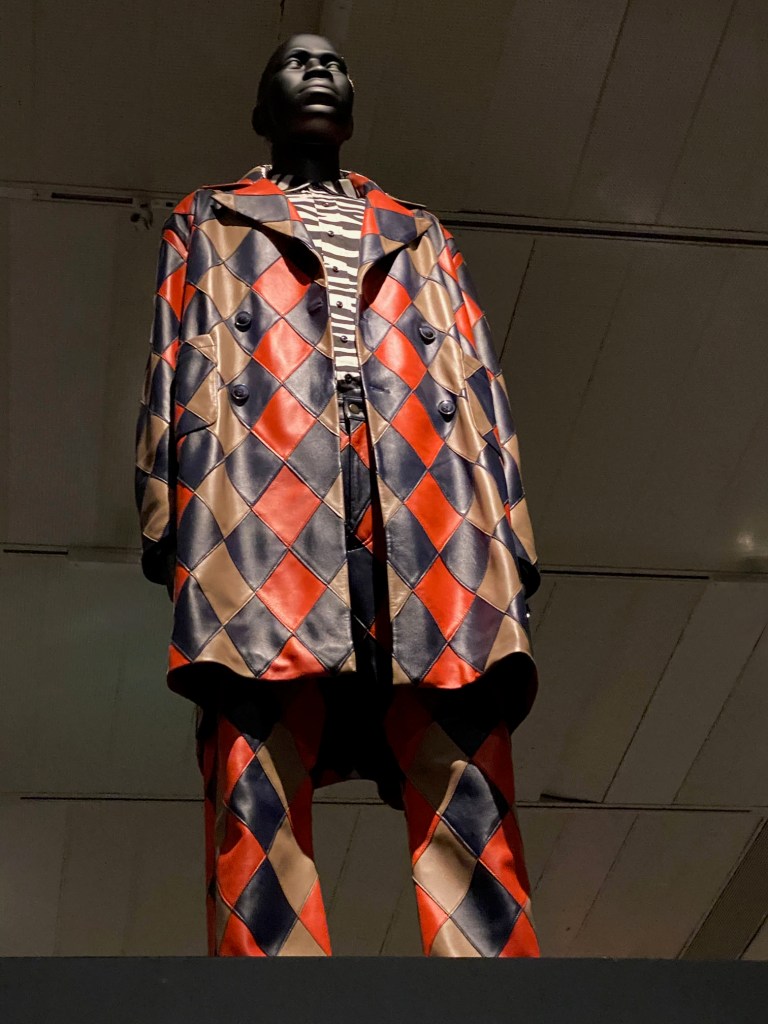

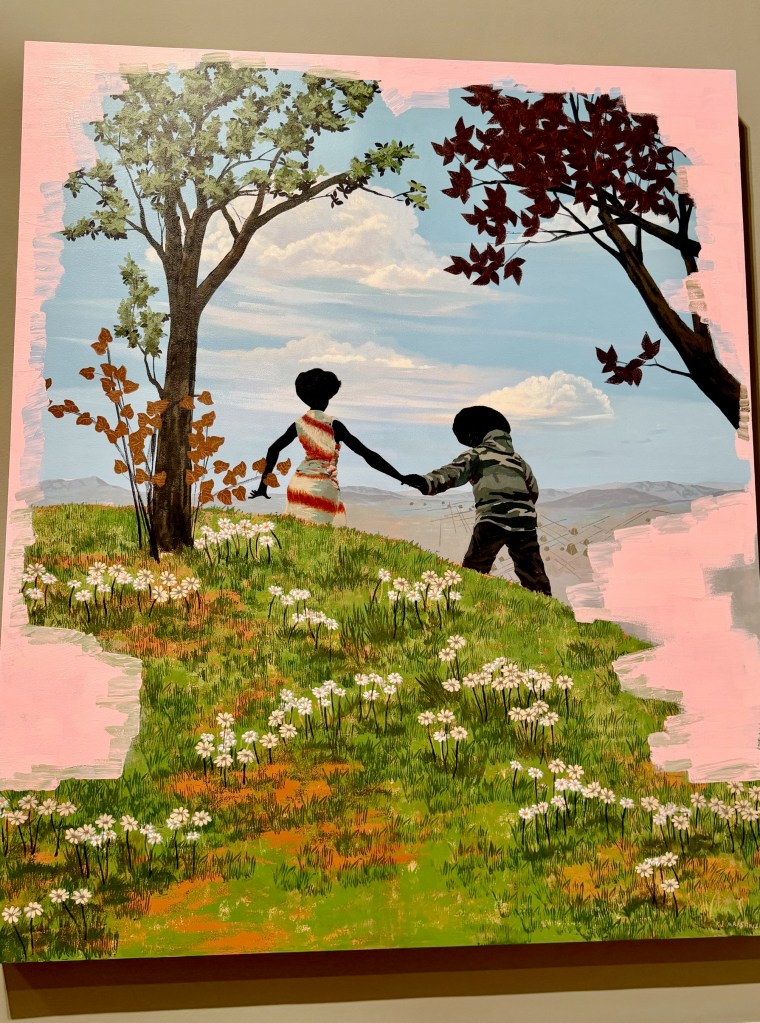

Marshall’s work fills eleven galleries of Burlington House with masterful paintings that put Black subjects back into the frame – Black citizens working in museums and art studios, delivering style in neighborhood barber and beauty shops, maintaining gardens in public housing projects, and wafting through floral fields à la Watteau and Fragonard.

Most of these scenes are presented on a large scale and jam-packed with art-historical, literary, and world-history references. In The Painting of Modern Life-themed gallery, his grand Past Times certainly evokes Parisian leisure-class epics by Manet and the Post-Impressionists. Marshall’s twist is to depict a wholesome, all-white-clad Black family enjoying its picnic lunch lakeside as music and lyrics by The Temptations and Snoop Dogg (literally) drift up from the radios to ask if this is “just my imagination.”

Take a quick look at the Academy’s exhibition preview video and hear Marshall talk about his inspirations and approach:

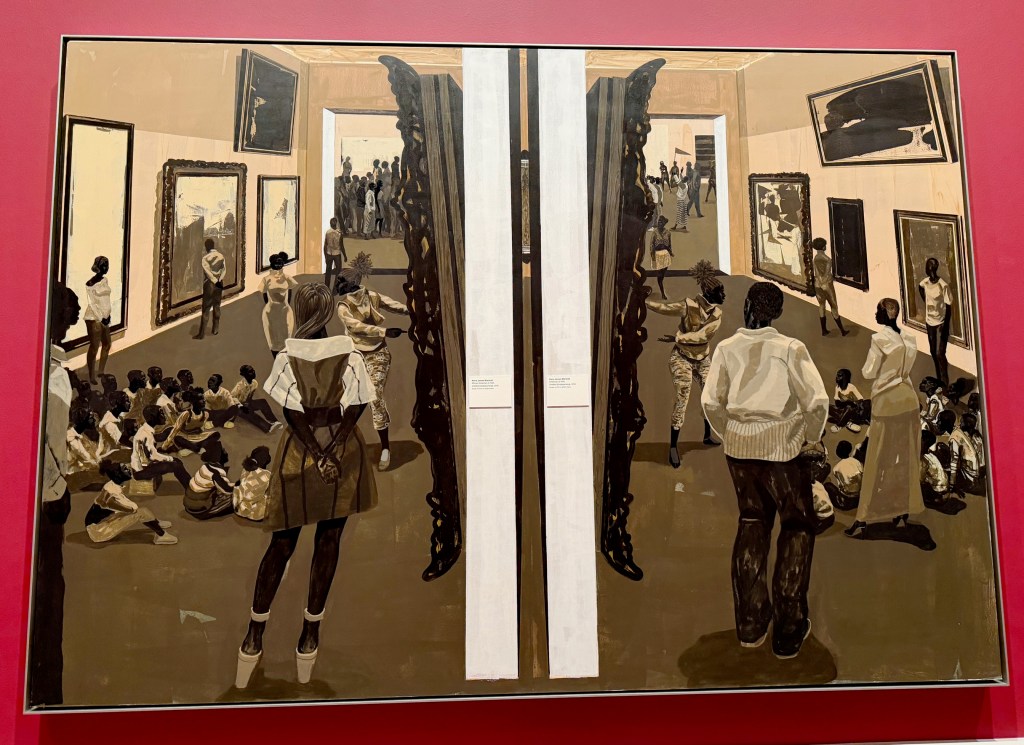

The exhibition begins with a gallery depcting self-confident artistic portraits, scenes from the academic art studio, and kids joyfully visiting a museum for the first time – a recollection of Marshall’s own exhilarating inauguration to a new world.

It’s followed by some of his earlier works inspired by Ralph Ellison’s 1952 Invisible Man and the similarly named 1897 book by H.G. Wells, with Marshall’s innovative black-on-black portraits.

Here’s a short video with Marshall describing all the different ways he uses black paint to create such vivid dimensionality:

Other modern-life paintings bring viewers unexpectedly into a world of gardens among Chicago public-housing complexes and a magical world of books awaiting eager young readers.

Other galleries are hung with Marshall’s assertive portraits of historic African-American abolitionist and literary figures, like Harriet Tubman and Phillis Wheatley-Peters, and tributes to 20th century political and cultural leaders.

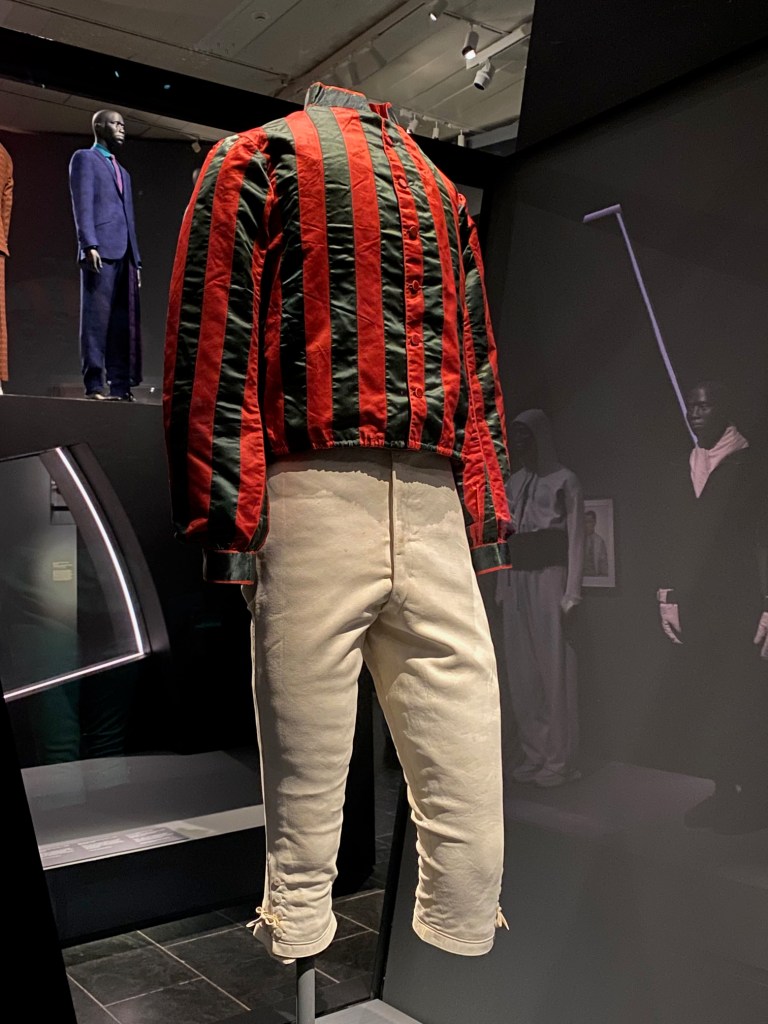

But the most talked-about works are Marshall’s grand canvases depicting the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade – a group of symbolic works on the terrors of the Middle Passage (an Atlantic crossing where many souls never made it to the far shore) and dramatic murals of the Africans who successfully facilitated the capture and sale of fellow Africans.

Visitors linger quietly in one of the last galleries devoted to Marshall’s installation at the 2003 Venice Bienniale. Most circumnavigate the sailing ship to get a better look at the hundreds with African-American achievement medals that are scattered about it. They also take close, respectful looks at each of the the commemorative ceramic plates that Marshall created with invented portraits of the first enslaved Africans brought to America.

Past, present, future, brilliant color, intriguing composition, successful Black protagonists – everything about the exhibition creates an indelible adjustment to what you thought you knew about daily Black life, lost history, and potential futures.

See more our favorite works in our Flickr album.

If you missed this show at the Royal Academy in London, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories will be shown at Kunsthaus Zürich from Februrary 27 to August 16 (2026) and at Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris from September 18, 2026 to January 24, 2027.