Although he’s featured at the back, the famous Sinclair dinosaur from the 1964 New York World’s Fair has generated a lot of attention inside the New York Transit Museum’s show Traveling in the World of Tomorrow: The Future of Transportation at New York’s World’s Fairs, closing today.

Drawn in by the spectacular photo of the monorail, commuters and tourists visiting Grand Central have been roaming through the gallery and gift shop, checking out the photos, murals, and Dinoland movie that whisk them back to the transportation pavilions of the history-making 1939 and 1964 New York world’s fairs. What’s a dinosaur doing in the World of Tomorrow? It’s all about the car.

The 1939 World’s Fair was built on top of the Corona garbage dump during the height of the Great Depression, putting visionary architects and day laborers to work.

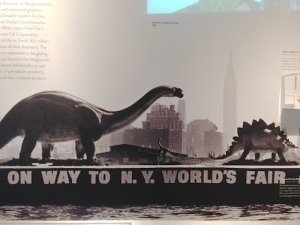

A 1964 New York Times photo of the Sinclair Dinosaur and Stegosaurus passing by the Empire State Building on their way to the Queens fairgrounds

A futuristic subway station was built to deliver visitors to the fairgrounds from the A Line. You could enter a spaceship-shaped Flash Gordon amusement ride and watch the first 3D Technicolor movie ever produced inside the Chrysler pavilion.

The best was the legendary Futurama, where people could imagine a time where everyone owned their own car. The ride took them to the faraway year of 1960. Superhighways and curly exit ramps bisect acres of tall skyscrapers, with cars traveling on autopilot at the amazing speed of 55 miles per hour. Incredible!

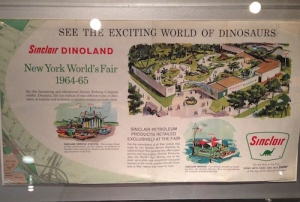

Fast forward: The Sinclair dinosaur is part of the 1964 experience. By then, every family owned its own car. Sinclair’s long-necked, supersized Brontosaurus was a familiar icon to any family stopping to gas up along the newly completed interstate highway system, so why not mix a little magic, promotion, and science?

Sinclair built Dinoland and populated it with life-size replicas of nine dinosaurs. The exhibition has plenty of Dinoland souvenirs along with a movie clip of families seeing the Jurassic giant for the first time.

Robert Moses and Walt Disney look at the model of the 1964 World’s Fair. From MTA Bridges & Tunnels archives

The show also pays tribute to the man who also brought another group of Mesozoic superstars to life inside the fairgrounds. Walt Disney designed four of the fair’s animatronics displays, including the robot cavemen and dinosaurs glimpsed in the Ford Motor Company’s “Magic Skyway” ride. There’s a terrific photo of New York’s Robert Moses alongside Walt, looking out over the model of the 1964 fairgrounds, and you can see the actual model itself, right inside.

Missed the show? You won’t see all the movies and hear the soundtracks that made the exhibition so exciting, but you can take a look at the galleries on our Flickr feed.