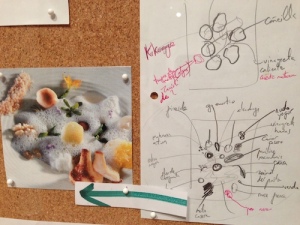

Notebooks and menu drawings from ElBulli’s kitchen displayed in front of a mural of Ferran Adrià and staff in Roses, Spain in the most famous kitchen in the world. Courtesy: elBullifoundation, The Drawing Center

If you weren’t able to visit the famed ElBulli restaurant on the coast of Spain before it closed two years ago, don’t worry. Pop down to Soho to meet the man, his team, and his legacy through The Drawing Center’s provocative show, Ferran Adrià: Notes on Creativity, running through February 28.

Even if you can’t taste the world-renowned creations, you’ll feel as though you’ve entered his kitchen during the six months per year that his team worked on R&D through up-close looks at experiments, plating, techniques, codes, inventions, and graphic treatises. Take a look at the installation on our Flickr feed.

Close-up of large working board of photo and diagrams document the plating and components of each dish. Courtesy: elBullifoundation

Last weekend, the Wooster Street space was jammed with visitors eager to see glimpse the genius behind the magic of the famed elBulli – notebooks filled with diagrams of exacting platings of food, a room inside the gallery evoking elBulli’s Barcelona archive, huge storyboards pinned with drawings and photographs of artist-inspired dishes, and glass-topped tables containing inventions that created some of the most amazing food–art in the world.

Examples: the apparatus that turns cheese into “spaghetti”, the glass bowls used to serve diners “edible air”, or the cocktail device that literally sprays a dry martini right into a diner’s mouth.

240 plasticine models used by staff to recreate precise shapes and portions of artistic dish components.

And how do you keep the beautiful dishes consistent? By making little plastic sculptures so that the kitchen crew knows how to duplicate forms for delicate platings precisely on everyone’s plate. When you’re delivering identical 40-course dinners to guests who have flown halfway around the world to join you for dinner, precision counts.

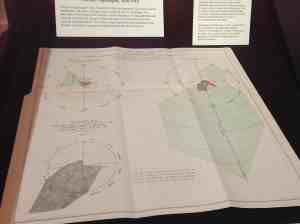

Improvisation may have happened during the six months of the year that elBulli shut down to devote itself to R&D, but not so much during dining-season crunch time. Just look at the large wall drawing that Adrià sketched for this show — Map of the Creative Process: Decoding the Genome of Creativity. Organization is key.

Last weekend, there were no empty seats in the downstairs video viewing gallery, as visitors sat mesmerized by 1846, the 90-minute film co-produced by The Drawing Center, showing every dish Adriá ever served at elBulli (1987 – 2011).

Plasticine model of the 1994 Le Menestra dish composed only of textures, including cauliflower mousse, basil jelly, almond sorbet, avocado, and numerous other components.

Photos of gorgeous, glistening food on plates, rocks, and wood lilted by to an opera soundtrack punctuated by the sounds of water lapping on the shore near the restaurant. Plates of vegetables, seafood slices, sprigs, and flowers wafted by. What are those spoons filled with? What appeared to be “hatching” out of that egg? What was the egg? What was perching on a stalk like an insect? The effect made you feel as if you were seeing life on Earth evolve…biomorphic shapes surrounded by foam.

You could tell that these art-and-food lovers had absorbed the exhibit upstairs when there was a collective gasp of recognition when the real-life version of La Menestra (accurately and lovingly represented in plascticene upstairs) floated onto the screen.

Since he shut the most desired and famous restaurant in the world, Adrià has been hard at work making sure that his thoughts, processes, philosophy, and research were well documented and translated to digital form. Although it’s still in beta, he’s incorporating it all into an online encyclopedia of gastronomic knowledge.

Kudos to Brett Littman and his team at The Drawing Center for mounting a show that pays tribute to food-as-art and shows us how creativity, inspiration, and documentation (in the hands of an genius, or team of geniuses) can turn experiments in a kitchen on a small Spanish seaside cove into a global digital export of wisdom and innovation for the next generation of chefs.

Take a look at Bullifoundation’s promo video to see what’s in store:

Happily, this show is going on the road in the United States before it leaves for The Netherlands in 2016: See it at the ACE Museum in LA (May 4-July 31), Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland (September 26-January 18, 2015), or Minneapolis Institute of Art (September 17, 2015-January 3, 2016).

Here’s a link to Documenting Documenta, a 2011 film about Adrià’s life, inspiration, work, and participation in Documenta 12, an international cultural festival in Kassel, Germany that happens every five years.