Feel like things are out of balance? Seven narrative painters let animals take center stage get visitors thinking about the future for nature and the world in Vivarium, Exploring Intersections of Art, Storytelling, and the Resilience of the Living World at the Albuquerque Museum through February 9, 2025..

Big, bold paintings let nature tell the story and present juxtapositions that present questions about society, environmental dissonance, and what messages animals might want to send. See some of our favorites in our Flickr album.

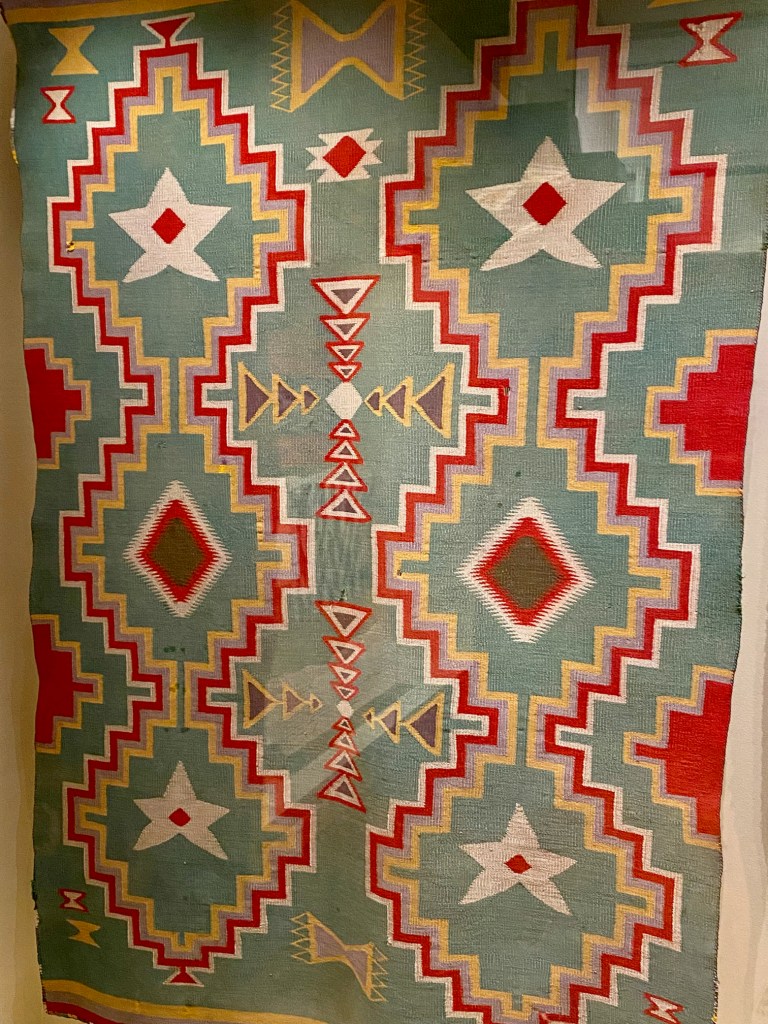

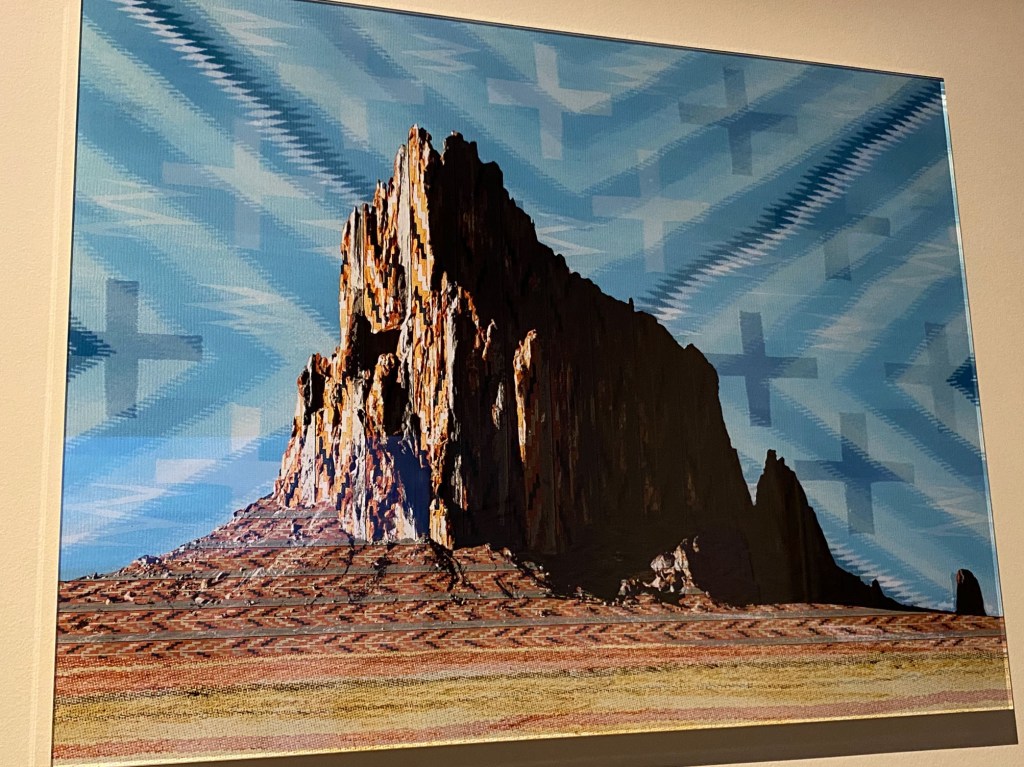

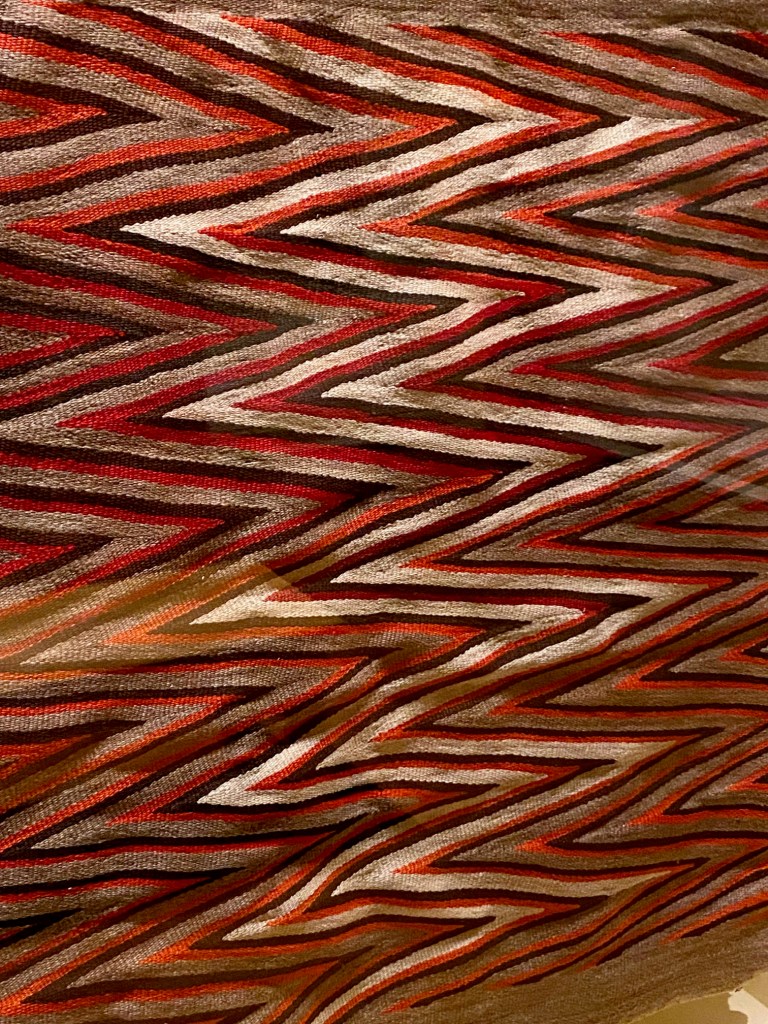

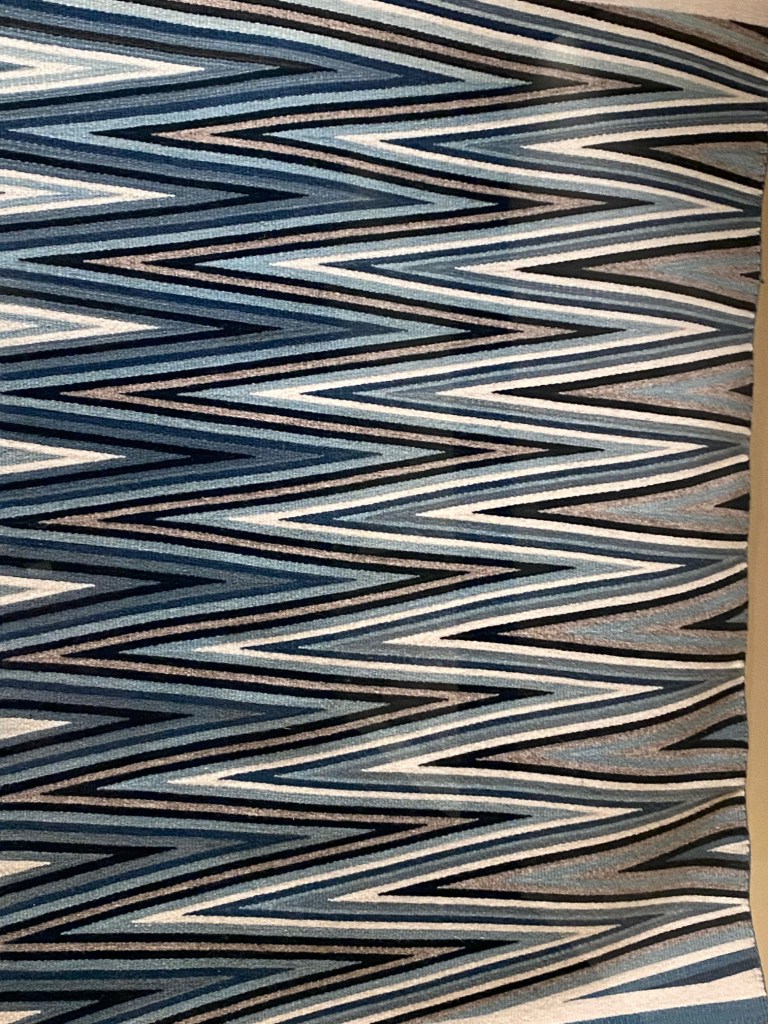

Although the exhibition begins with a small selection of works from Santa Fe’s Tia Collection – Dan Namingha (Hopi-Tewa), Nanibah Chacon (Dine/Chicana), and others – the majority of the space features a selection of works by the seven featured painters. Clusters of paintings immerse viewers in each artist’s unique world, style, and narrative – mini-vivariums, or artificial worlds.

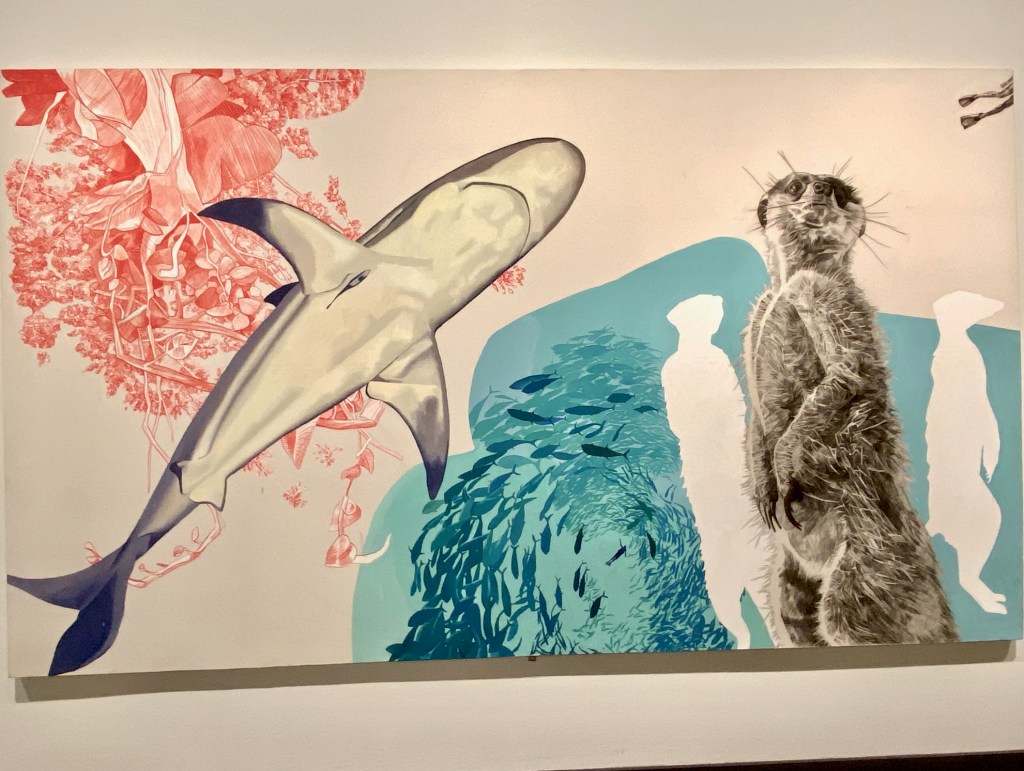

Nature explodes of Nathan Budoff’s giant canvases – tigers, meerkats, swimming octopii, schools of fish, prarie dogs – all floating and interacting in a pure, white space. He creates realistic depictions in charcoal, oil, acrylic, and ink, but juxtaposes natural components that are startling. Visitors stand back, pause, take it all in at once, trying to make sense of how these magnificent creatures interact in unusual landscapes. Mostly, the canvases do not include people, but Nathan enjoys letting the remarkable, minutely observed wildlife speak their own truths.

Paintings by Patrick McGrath Muñiz are intellectual puzzles, mixing modern issues, depictions of modern technology, and classical Renaissance and

Baroque painting techniques. Signs, symbols, and details on the horizon demand slow scrutiny to unravel the allegories and associations packed into the paintings.

Eloy Torres, a Chicano activist and muralist, uses religious, mythological, and surrealist pictorial conventions to construct worlds that lets the viewer their intuition to connect the dots.

Stephen J. Yazzie (Laguna Pueblo/Diné) exhibits a series of works in which Coyote inhabits upscale suburban interiors, emphasizing the inside/outside, nature/culture dichotomies in contemporary life.

Julie Buffalohead (Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma), a member of her tribe’s Deer Clan, creates narratives featuring animals as protagonists, often metaphors for interactions between natural and spiritual realms. Large works allow players in her stories to prance, dance, and float across saturated color fields.

Artist/educator Stan Netchez (Shoshone/Tataviam) presents a throught-provoking masterpiece, using Picasso’s Guernica imagery, US brands, and indigenous spiritual icons to display the chaos and destruction inflicted on indigenous peoples.

Listen in on a panel with four of these storytellers conducted by the Albuquerque Museum.