1730s Dutch brocaded satin showing exotic Asian islands and fauna was refashioned in 1770 into a more fashionable French look. Source: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A joyous collaboration among eight departments of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has written a new history of how a global network of fabric trade and manufacture once served the same purpose that YouTube, music videos, shelter magazines, Vogue, and The New York Times Style section do today – to present images of the latest trends and make anyone in the world that sees them understand the clothes or accessories needed to be “on trend” with other sophisticates.

Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800, running through January 5, tells a monumental story about how trends went viral pre-Internet. It was a slower world dominated by sailing ships versus transoceanic cables, but the tale spanning centuries, continents, and cultures shows how gorgeous garments, incredible tapestries, bedazzled church vestments, quilted bedding, luxurious wall hangings, tour-de-force printed fabrics, and royal furniture telegraphed “trend” in a different way.

Embroidered muslin dress. The 18th c. European Neoclassical craze drove massive imports of airy Bengali muslin. Source: The Met

The show can’t fully be appreciated in just one walk-through. Each textile and garment is incredible to behold, and the network of interrelationships among craftsmen, artisans, tradesmen, royal buyers, rich merchants, and brave sailors traversing strange shores is equally rich, complex, and layered.

This two-dimensional pageant, enhanced by exquisite gowns and garments whose fabrics were sourced from the four corners of the globe, is given the full-bore treatment in the top-floor galleries reserved for blockbusters.

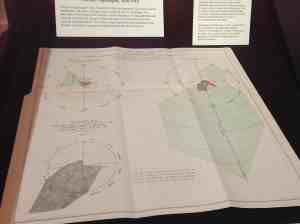

How do you tell a story this big? The curators decided to put a large interactive map of the 16th- to 18th-century trade routes right inside the door, which brings you up to speed on the French, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and British trade routes linking the Americas, India, the Orient, and islands.

Then come the galleries dedicated to the styles and fiber-tech associated with each – silks woven in China for Europe and Japan, Spanish embroideries that reference Islamic carpet borders, weavings made by Peruvian grand masters of the art, and Indian resist-dye masterpieces that turned into English chintz and fabrics for the King of Siam.

17th c. Japanese Jinbaori made from Dutch wool and Chinese silk, a luxury item worn over samurai armor. Source: John C. Weber Collection

In the Spanish gallery, you’ll see how the crowned double-headed eagles of the Hapsburgs adopt kind of a Chinese-phoenix look when 16th-century Iberian traders commissioned silk artists in Macau to create silk they could sell back home. By the 17th century, everyone – East and West – had become accustomed to enjoying “exotic” images from halfway around the world – birds, animals, architecture, flowers, and landscapes. It had the same impact as Google Earth and World Wide Web access today.

One of the more startling facts is that before Commodore Perry “opened” Japan to the West (ref. Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures, the musical), Japan was more into luxury-goods consumption than production. Apparently, the trend was to import the ultra-luxury, Dutch wool, and make it into topcoats that Samurai warriors could drape over their armor.

If you don’t see this in person, visit the online exhibition site for an encounter that’s a real treat: You’ll get to zoom into each quilt, drape, embroidery, dress, shawl, and piece of fabric to see it all super-close.

A late-18th century Indian-chintz Dutch jacket that knocked-off a French designer jacket in pink French fabric. Both have similar exotic floral prints. Source: The Met

Click on the “full screen” button on each and toggle in to examine all of the glorious detail. The web site will tell you the story and show you the items in each gallery. You’ll be surprised to find the genesis of the fabrics-on-walls interior-decorating craze for country homes in the late 1700s and how men-only clubs adopted both plain and exotic dressing-gown dress from the Orient (a style also featured prominently in the current FIT show).