Gus Baumann, America’s greatest master of color woodblock prints, never considered himself a fine artist. Nevertheless, his prints, sculptures, paintings, commercial art, furniture, and marionette stages fill four galleries in his grand retrospective at the New Mexico Museum of Art – Gustave Baumann: The Artist’s Environment, on view through February 22, 2026.

Demand for Gus’s intricate block-printed sun-dappled Western landscapes from the 1920s through the 1950s still runs high. So, it’s a treat to learn how Gus achieved such a high degree of technical proficiency early in his career, lived Arts and Crafts philosophy, relished immersion in art colonies, and found his family in Santa Fe.

See some of our favorites in our Flickr album.

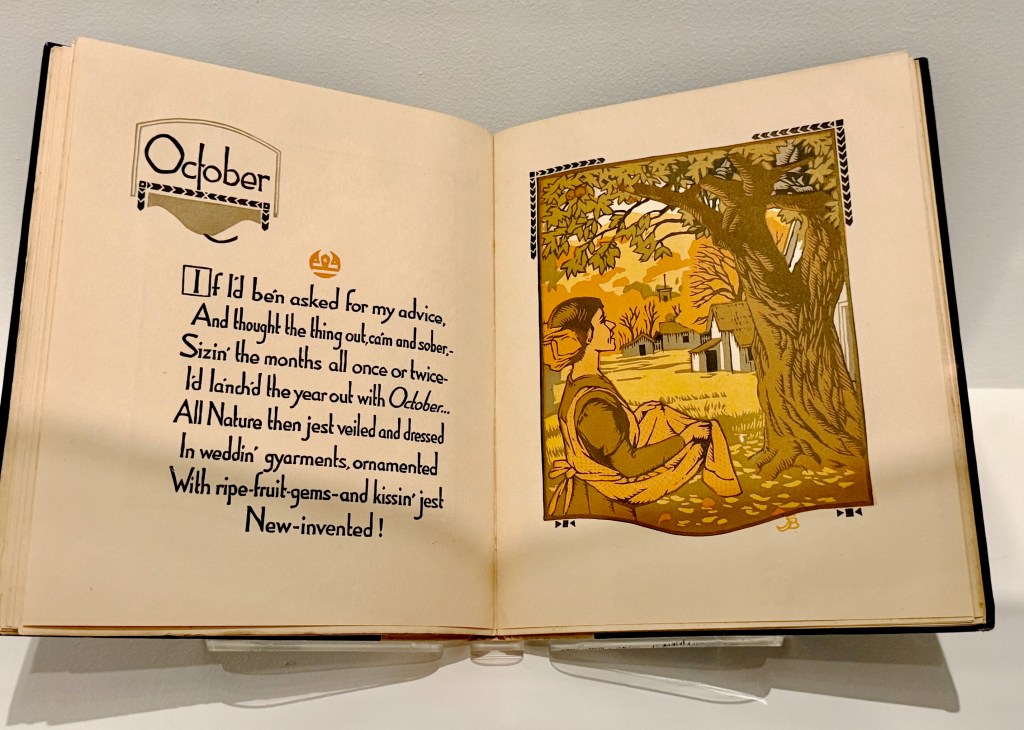

Although Gus was born in Germany in 1881, his family emigrated to Chicago when he was around ten. His father was a craftsman and woodcarver, and it left an impression. The first themed section of the exhibit – “Finding His Way”– gives a glimpse into his family background, early commercial art work, wood carving expertise, and furniture he designed later in the 1930s.

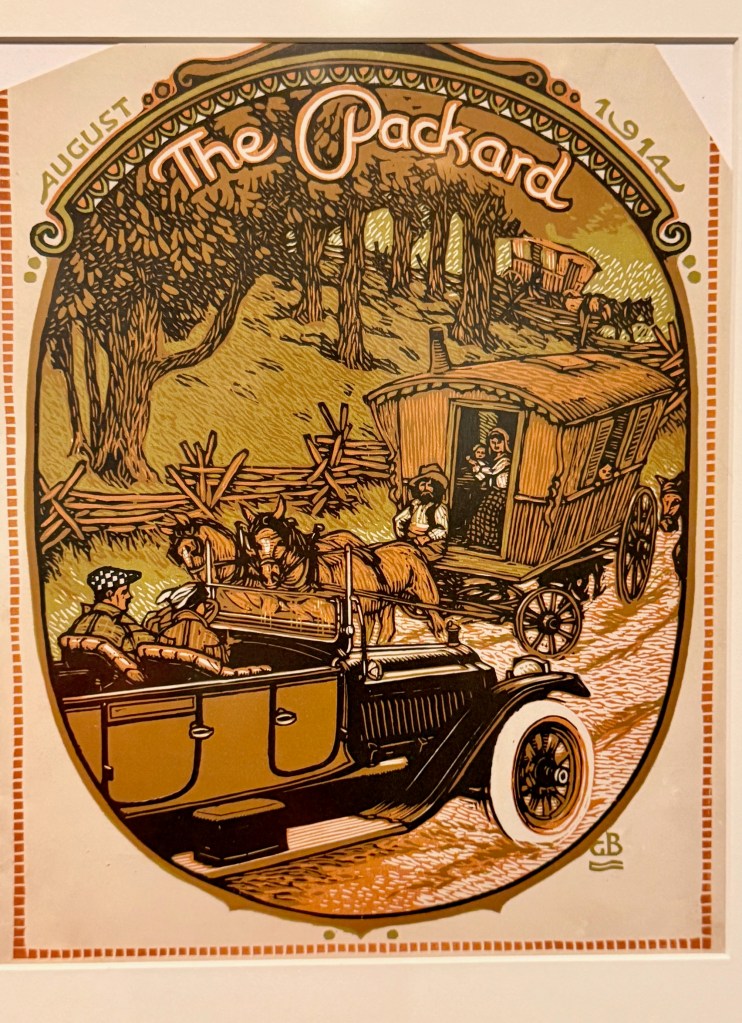

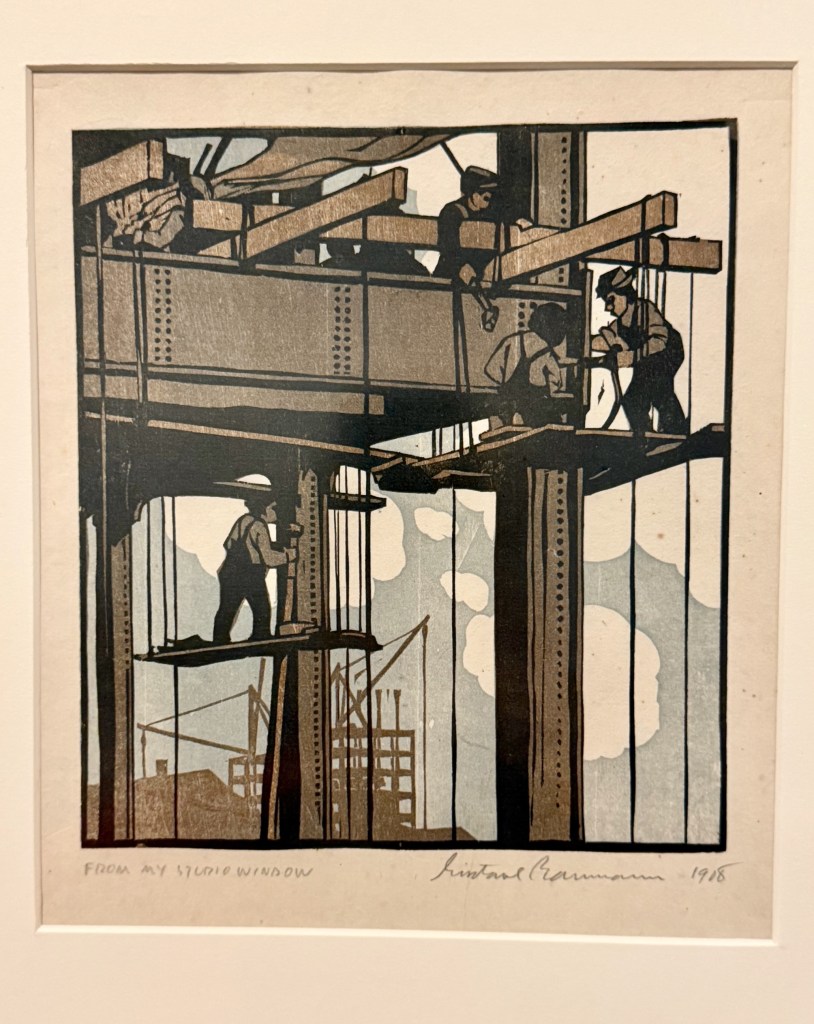

When he was 17 and his dad left the family, Gus had to find work to help his mom make ends meet. He worked full time at a Chicago wood-engraving shop that cut illustrations for books, magazines, and newspapers. When he was 20, Gus opened his own wood-engraving studio.

To fine tune his skill, he attended Munich’s Royal Arts and Crafts School for a year to learn from the best German color wood-block print masters – a move that chose traditional skills over academy fine-arts training. When he returned to Chicago, he opened Baumann Graphic Art Service.

Although Gus found success, his love of craft and traditional printmaking methods drew him to an art colony in Nashville, Indiana that revered traditional crafts and a slower pace of life. The second section of the exhibition – “A Rolling Stone” – highlights work he did in Munich, his acclaimed print series featuring Indiana craftsmen, coastal life in Provincetown, and the electricity he felt in New York.

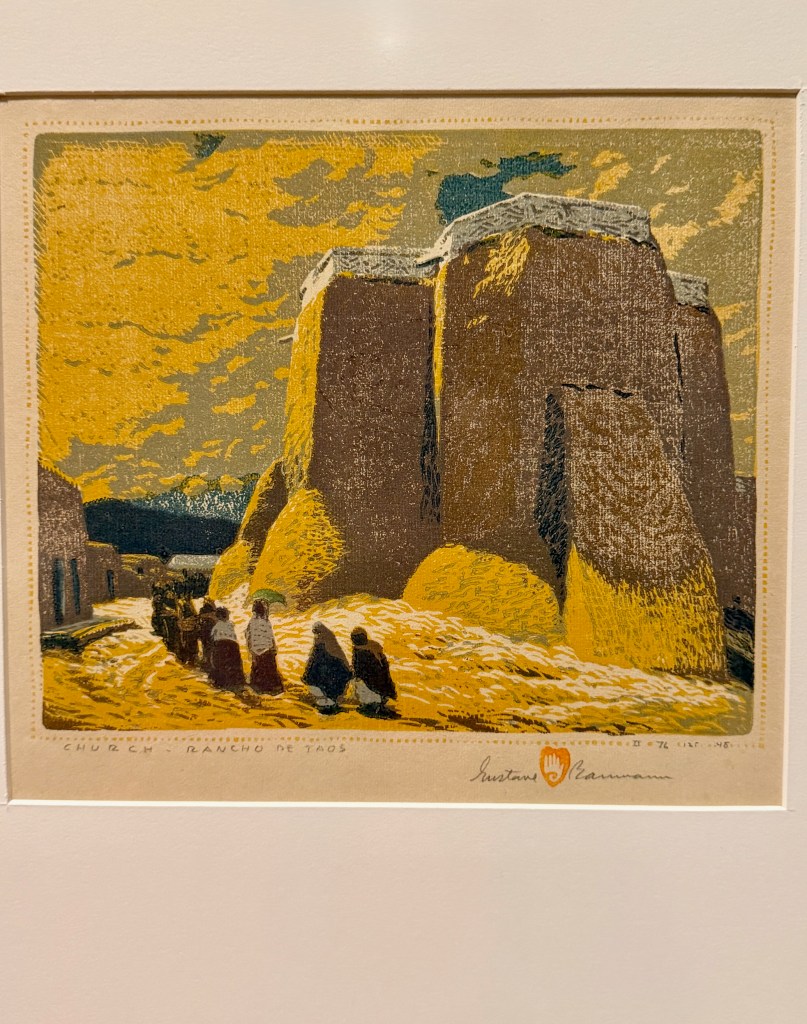

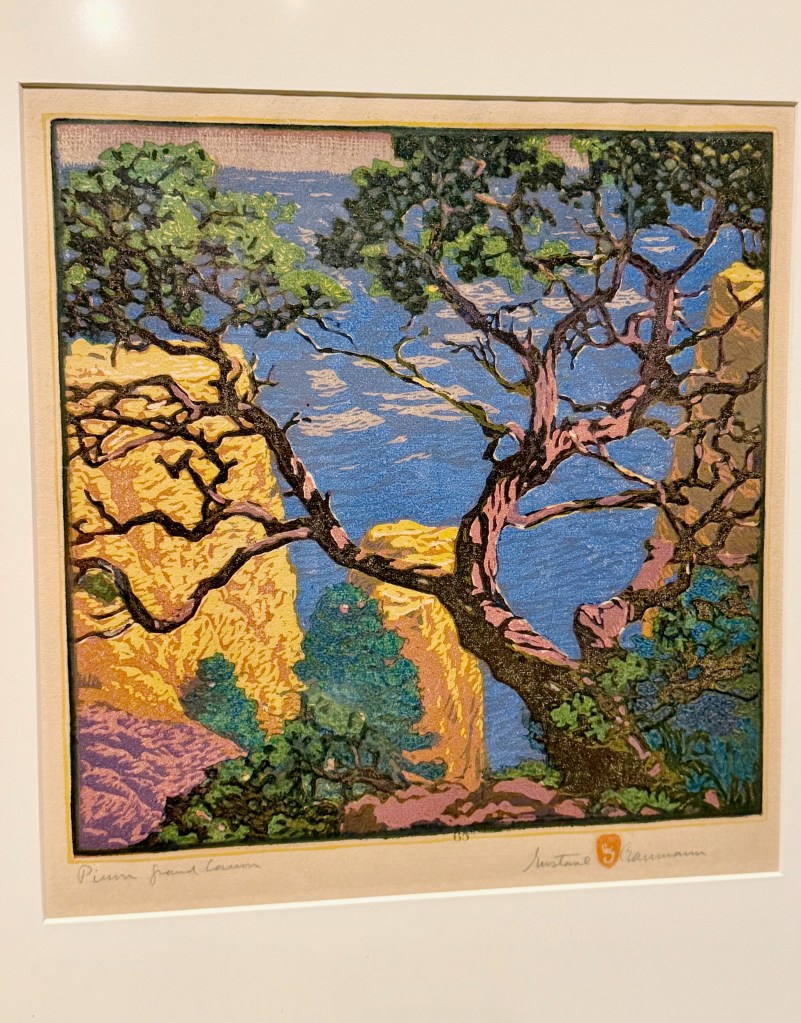

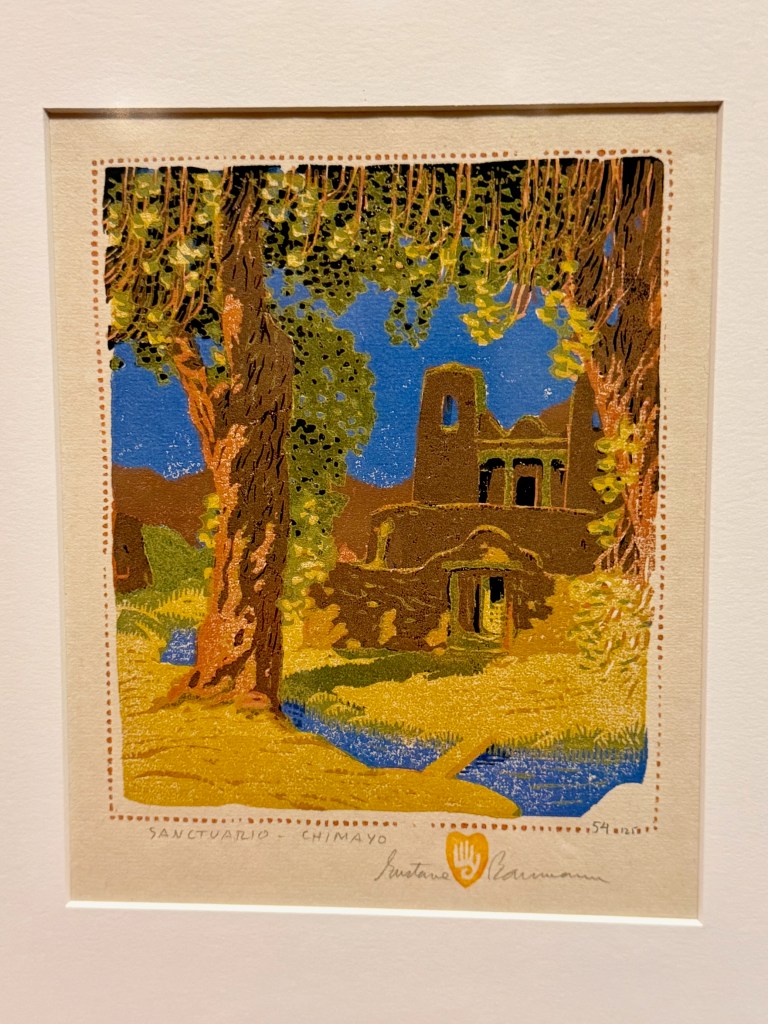

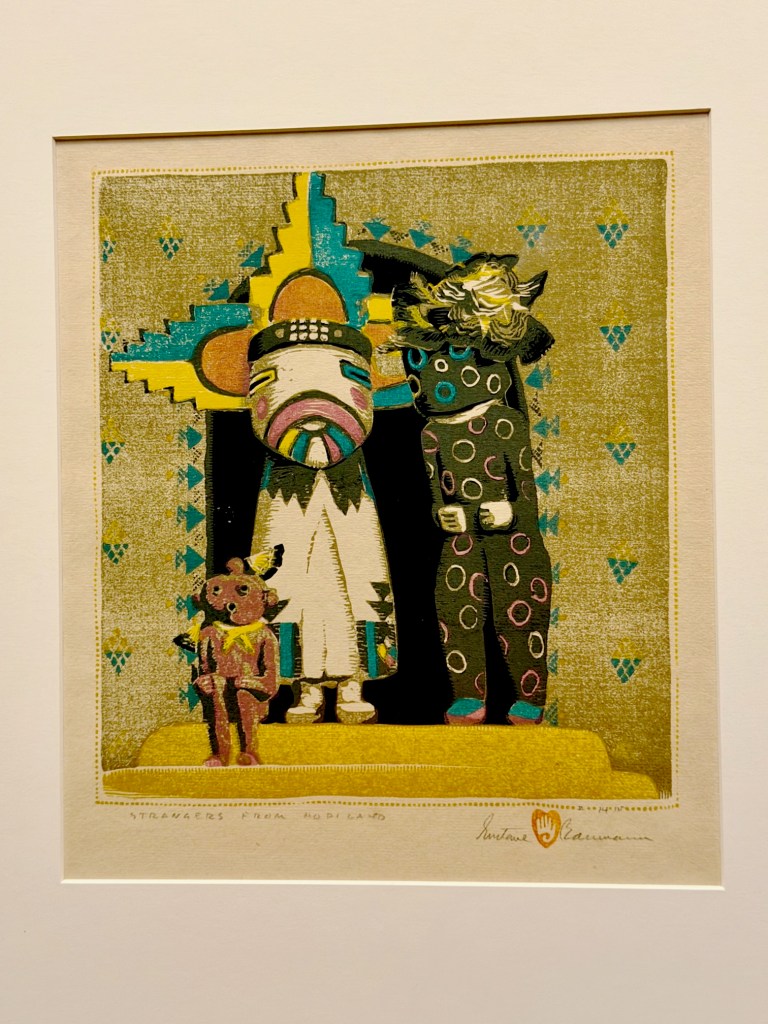

But his life would change forever when he traveled West and landed in New Mexico in 1918. Due to his reputation as an award-winning printmaker, Santa Fe welcomed him with open arms. Gus was struck by the unique Hispanic and Pueblo ways of life, the beauty of the Southwest, and the growing art colony in Santa Fe.

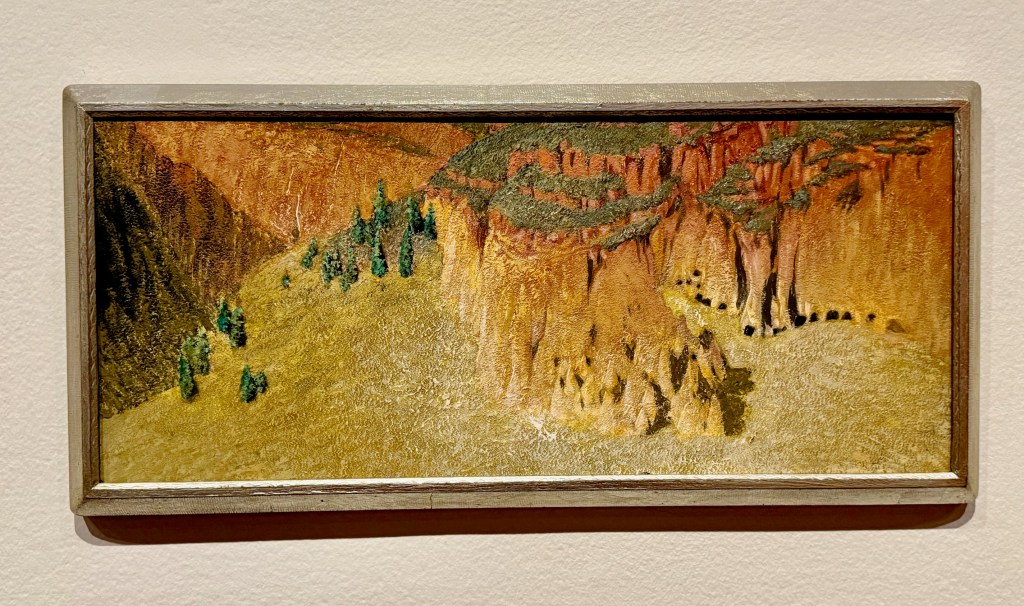

Before long, Gus was making and selling gorgeous prints, traveling to archeological sites, attending dances at the pueblos, soaking up the ambience of ancient Spanish churches, and putting brush to canvas, and partying with his new artist friends. And he met Jane, the love of his life, and started a family – creating a life full of fun, art, play, and community service.

Since Jane and Ann Baumann donated so much of Gus’s work to the New Mexico Museum of Art, the curators were able to display finished prints alongside drawings and wood blocks that give visitors insight to his process. One long wall dissects his multi-color printing process for his famed Old Santa Fe – the initial drawing, the separately carved color blocks, single-color proofs, multi-color runs, and the finished six-color print.

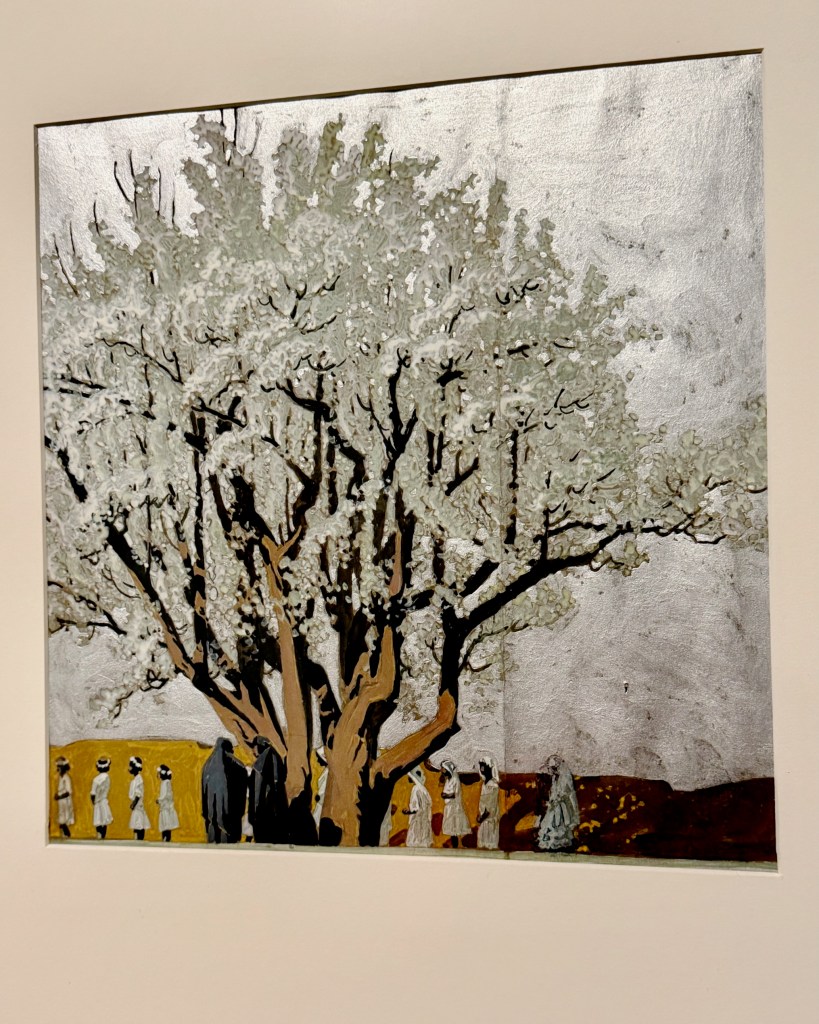

Nearly a half-dozen example of Gus’s watercolor paintings and finished prints are displayed side by side. Visitors are delighted to stand, look, compare, and wonder how he conceptualized steps to carve blocks for each color and achieve images of such depth and vibrancy.

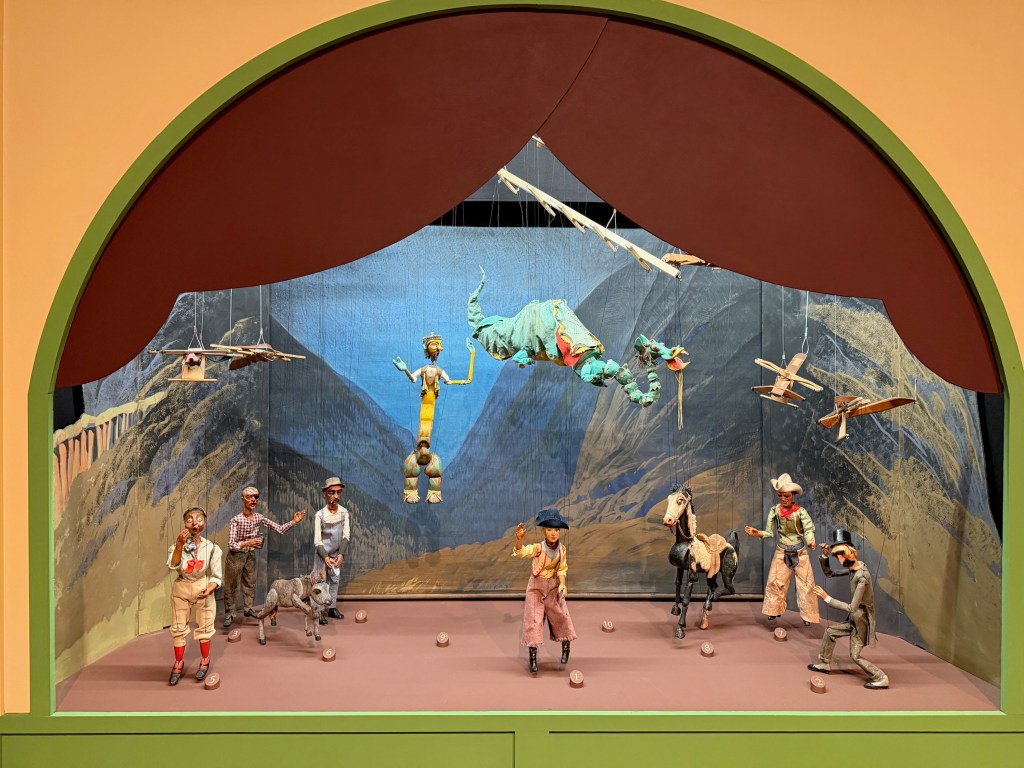

The final gallery “An Artist by Accident” displays an array of intricate color woodcuts, experimental paintings, satirical works, paintings Spanish religious icons, whimisical wood carvings, and everyone’s favorites – Baumann’s marionettes.

It’s the first time Gus and Jane’s marionette casts have been displayed in decades, complete with hand-painted backdrops – scenes representing just a few of the couple’s scripted shows that they performed at home, in venues around Santa Fe, at world fairs, and on tour.

Whimsey, delight, innovation, social commentary, and fun are all there, with surprises unfolding around every corner. And this is all just a fraction of Gus’s creative output from his coming-of-age in the horse-and-buggy era to the Atomic Age.

No, he didn’t follow the traditional academic path, but he did leave his creative touch on America’s printmaking traditions, the foundation of many Santa Fe cultural and historical institutions, and the care and feeding of a state full of artists as head of New Mexico’s New Deal artist programs.