Cunningham’s photo of Editta Sherman in period dress on a 70s graffiti-covered subway car going to a shoot at the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens

Uber-fashion documentarian Bill Cunningham had a great idea in 1968, just as NYC was sliding toward financial crisis, crime, and (goes without saying) neglect of architectural sites, like Grand Central. Why not celebrate two centuries of NYC fashion and splendor on the street?

What were people wearing when some of the City’s most iconic homes, churches, and public buildings were built? Was it possible for a black-and-white photograph to reveal some new insight about the City from combining fashion, architecture, and a little fashion flair and attitude?

Editta poses for Bill in embroidered frock coat and breeches in front of St. Paul’s Chapel, the oldest church building (1766) in Manhattan

Results of Bill’s eight-year project are on display through July 15 in the Bill Cunningham: Facades photo exhibition on the second floor of the New-York Historical Society.

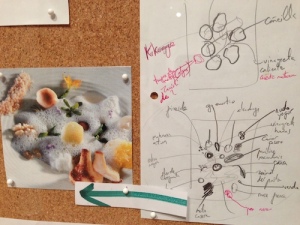

Without the aid of Wikipedia, he researched the years that some of his favorite historic places were built, and began scouring thrift stores for get-ups from the matching decade. He enlisted his muse, Editta Sherman, a fellow photographer and neighbor at the Carnegie Hall studios. For the next eight years, Editta and Bill went on weekend odysseys throughout the City, modeling and documenting over 500 historic outfits in front of interesting but sometimes forgotten facades.

In 1976, Bill gave 88 of his silver-gelatin prints to NYHS – the core of the current show, which is hung to emphasize the chronology of fashion and architectural style. The show was jammed with fashion lovers last weekend, soaking in the details from Bill and Eddita’s journey back in time.

Editta dresses for Bill in Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s own Callot Soeurs at the 1904 Harry Payne Whitney House

It starts with Editta dressed in an 18th c. embroidered coat and breeches in front of the 1766 tower of St. Paul’s Chapel at Broadway and Fulton – the oldest church building in Manhattan that was considered “suburban” when President Washington lived here. Remarkably, they discovered this satorial gem in a Ninth Avenue second-hand store.

The visual treats just keep coming – a diaphanous Empire muslin on a model in front of City Hall (1803), Civil War-era frocks at Sniffen Court in Murray Hill, bustles and parasols at the 1884 Villard Houses (Helmsley Palace), and many spectacular gowns from the Gilded Age. Consider Eddita channeling “Diamond Lil” in front of 1891 Delmonico’s, the first modern American restaurant that innovated a la carte dining, private dining rooms, Lobster Newberg, and Baked Alaska.

In two photos, the team managed to borrow some historically relevant gowns – Gertrude Whitney’s Callot Soeurs frock for the shoot at the 1906 Payne Whitney home by Stanford White (Fifth & 79th) and Mrs. J.P. Morgan’s Worth gown at the gazelle gates of the Apthorp.

The curators note that although women’s fashion in the early 20th century was fairly liberating, the public architecture of New York remained tightly classical. The show’s final shots soar with the optimism of the modern – the “New Look” in front of the Paris Theater (1948), full-skirted flair on Park Avenue by the Lever House (1952), Givenchy at the Guggenheim (1959), and mod looks at the GM Building (1968).

You will savor every minute of your journey with these creative geniuses. Check out a few photos on the NYHS web site, find a copy of the 1978 book Facades, or get to the show.

If you didn’t see the film about Bill, rent it from iTunes or Netflix or buy the DVD. You can glimpse Eddita (a.k.a. The Dutchess) in the movie trailer below:

![Timothy O’Sullivan’s 1865 photograph, High Bridge, Appomattox, Va. from Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War [c1866] Source: Library of Congress](https://itsnewstoyou.me/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/highbridge2.jpg?w=300&h=229)