Detail of Elijah Burgher’s The Pattern of All Patience 1 (2014), featuring magical symbols, installed on the second floor

It’s the last time the Whitney Biennial is holding its big, expansive, colorful, and provocative shindig on the Upper East Side, since it will decamp to its new riverside home at the foot of the High Line next year. Go before it ends on May 25.

It’s amazing to think that this is the 77th time that the Whitney has hosted either an annual or biennial show to showcase the best of American art, as controversial and impossible a task as that may be. This year, the Whitney threw in the towel in trying to showcase “the best” of what’s going on in contemporary art coast to coast. It just wasn’t possible given the expanse, diversity, and barrier-breaking works that American artists are cranking out right now.

Instead, the Whitney invited three innovative curators to choose what should be shown on each of three floors and around town. (Yes, there are offsite works, too.)

The divide-and-conquer approach works, resulting in a fun variety of media, installations, paintings, sculptures, textile art, performance, and collections-as-art. The team pulled it all together in only 18 months while still doing their day jobs at Chicago’s Art Institute, London’s Tate Modern, and Philadelphia’s ICA.

Visit our Flickr album and walk through the press preview with us, where several artists were on hand in the galleries with their work.

It’s a happier, lighter show compared to past Biennials, but that doesn’t mean that the artists ignore social commentary or darker sides of human nature. It just means that you won’t feel as though you need a graduate degree in Conceptual Art to enjoy and ponder the work you’ll encounter.

Highlights: Charlemagne Palestine has created a surprisingly spooky installation in the stairwell that features sonorous sounds emanating from speakers adorned with stuffed animals. LA painter Rebecca Morris has two bright, gigantic delightful paintings on the second floor, curated by Philadelphia’s Anthony Elms, which features several satisfying collections-as-art installations by Julie Ault, Richard Hawkins, and Catherine Opie.

Fans of NYC’s 1970s art scene (when Soho was still industrial) will be captivated by The Gregory Battcock Archive, peering at the ephemera collected by one of the decade’s most prominent art critics who died under mysterious circumstances in 1980. Amazingly, it was all found by artist Joseph Grigley wafting around garbage bins in an abandoned storage facility. Grigley’s created a disciplined, loving, and intimate installation of reclaimed Battcock mementos, memories, and letters with Cage, Warhol, Moorman, Paik, Ono, and other 70s superstars.

The top floor takes a down-home approach to some very enjoyable paintings, sculptures, installations, and ceramics. Midwest curator Michelle Grabner said that she wishes she could just camp out there for the run of the show. You’ll enjoy it, too — a dreamy installation by Joel Otterson, a monumental yarn pillar by uber-fiber-artist Sheila Hicks, a witty desk and bookcase by master woodsman-sculptor David Robbins, and shelf of delicate and whimsical ceramics by Shio Kusaka.

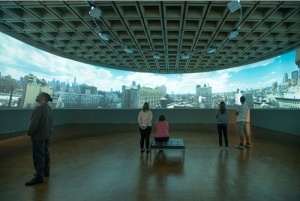

The third floor, curated by Stuart Comer (who’s recently moved to MoMA), features a lot of screens and digital media, essentially making you think about art in the age of the iPhone. As you step out of the elevator, you’ll encounter Ken Okiishi’s series of painted panels. Oh, wait! They’re actually abstract paintings on upended flat-screen TV displays – sort of like what would happen if Kandinsky’s Seasons were done at the Samsung plant.

The mixing of media keeps morphing in room after room of clever installations by Triple Canopy (antiques meet 3D printing) and Lisa Anne Auerbach (knitting meets social commentary, and zines meet the Giant in Jack and the Beanstalk). See Lisa’s work and listen to her explain her knitting:

There are dozens of other videos and audio guide stops posted on the Biennial web site (click on “watch and listen”), as well as bios of all the artists.

Alert: MAD’s own design biennial opens July 1.