Fancy neck ruffles, gilt-framed portraits, sleek suits, flowing trousers, and bold plaids and stripes pop from every corner of the Costume Institute exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 27.

It’s a 12-chapter journey through Black men’s style that emphasizes how superb tailoring, style, and fashionable precision has been used successfully by newly emancipated slaves, Revolutionary political leaders, activists, sports and pop stars, and high-style travelers from the 17th-century through today.

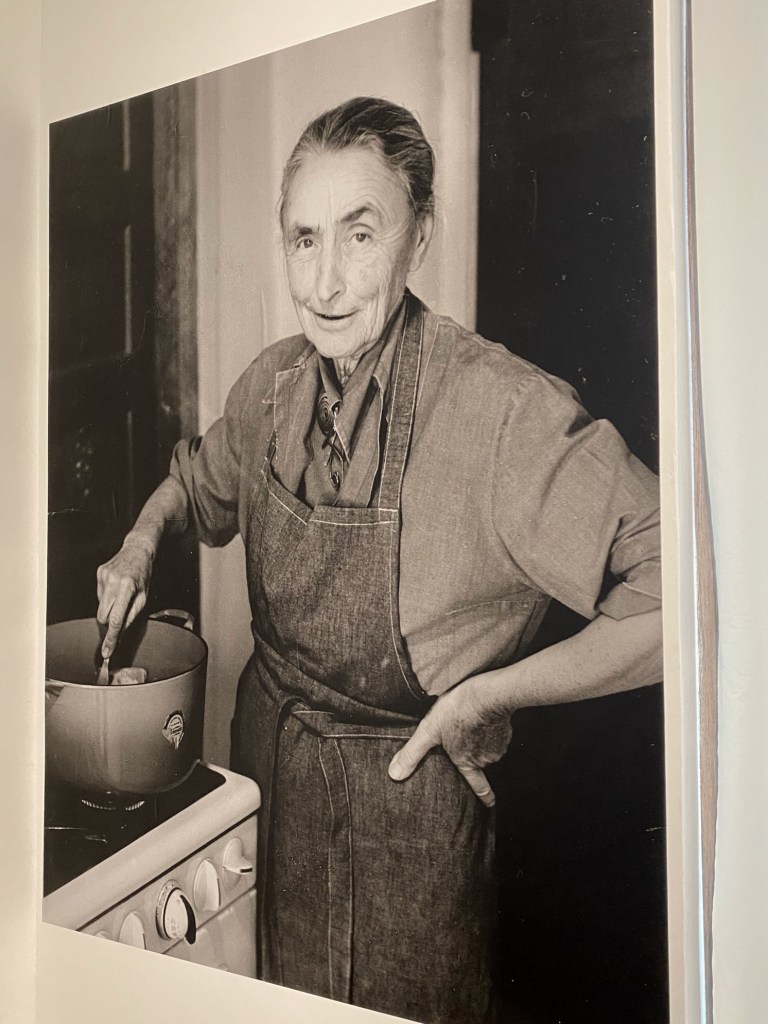

Each section provides a deep dive into history to explain how Black men (and a few daring women) adapted high-fashion menswear in the 17th and 18th centuries to reinvent themselves as authoritative, free, cosmopolitan high-achievers. Themes include Presence, Distinction, and Cool – based on co-curator Monica L. Miller’s acclaimed 2009 book, Slaves Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity.

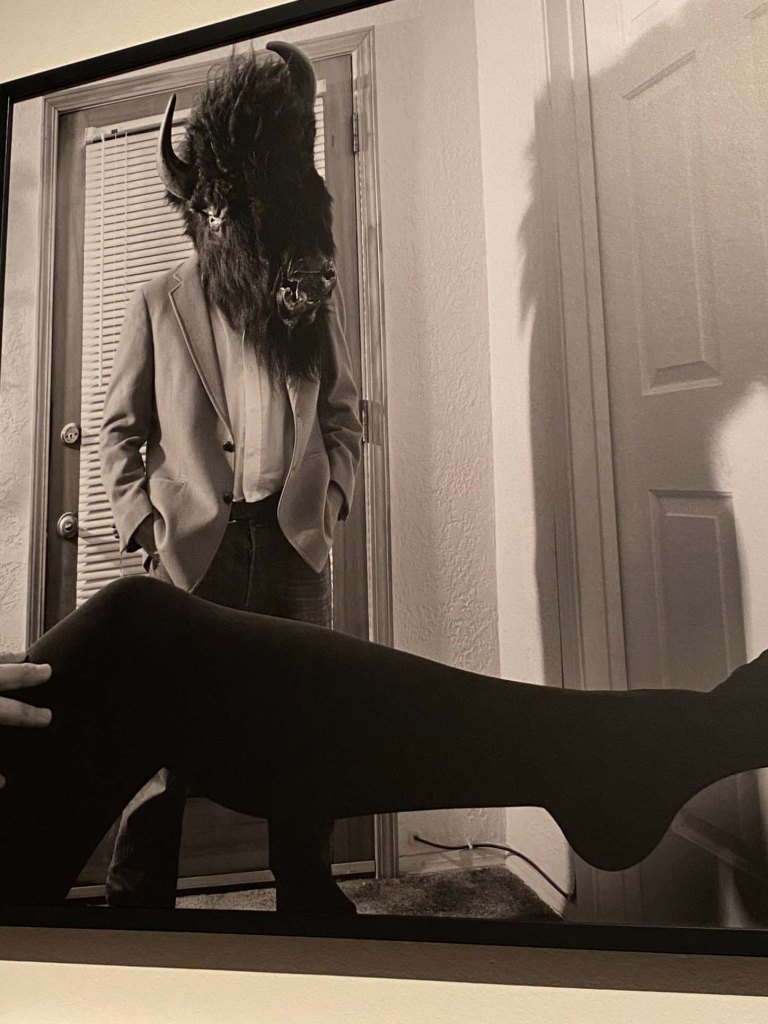

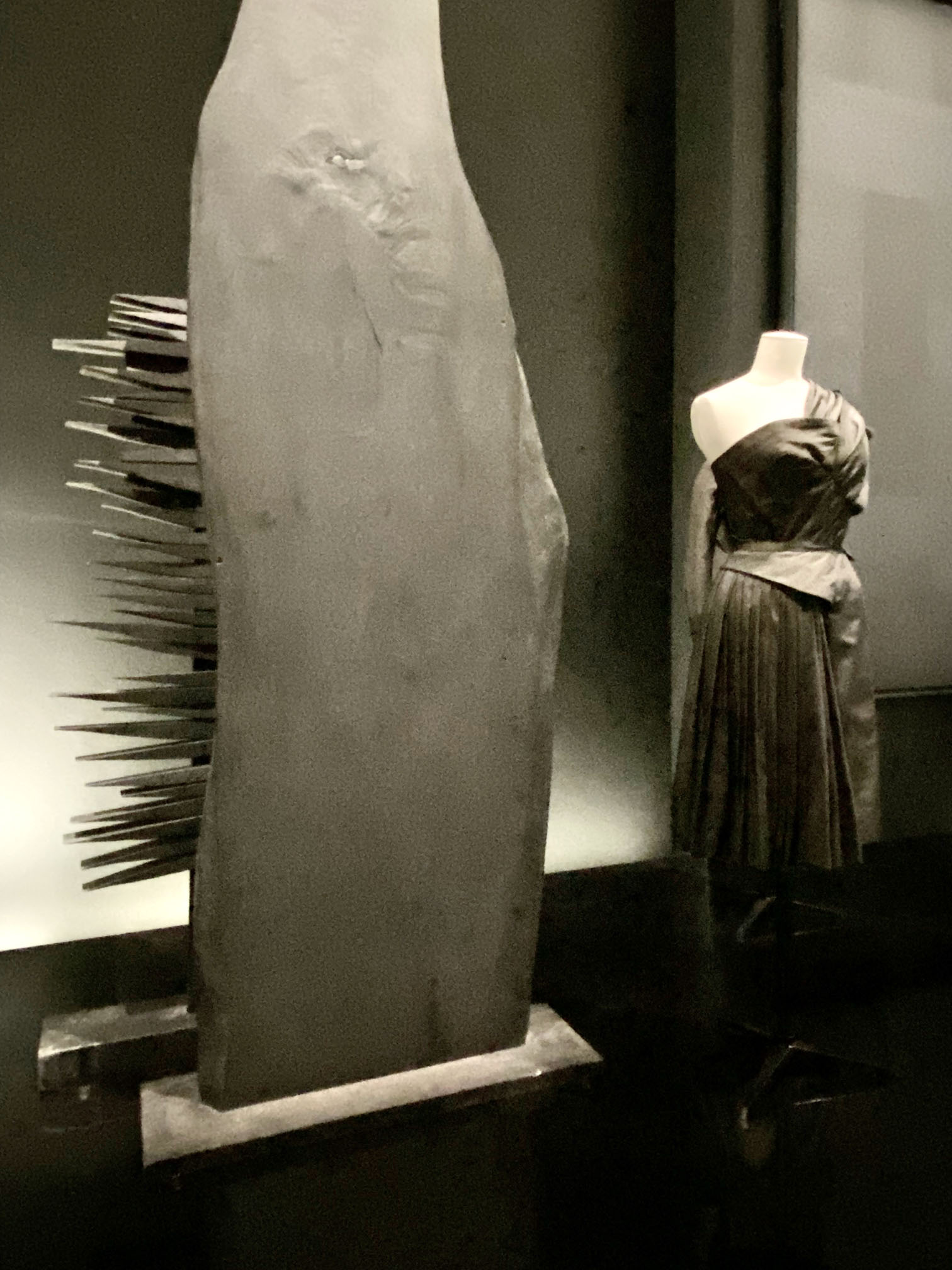

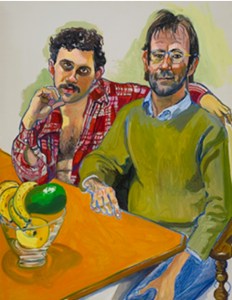

The curators leverage the Met’s extensive collection of photos, books, magazines, fashion, and accessories to provide visitors with the full visual story of each of the angles of Miller’s treatise. Plus, they’ve assembled loans from recent collections of cutting-edge contemporary Black designers who themselves are pulling inspiration from these same pages of history.

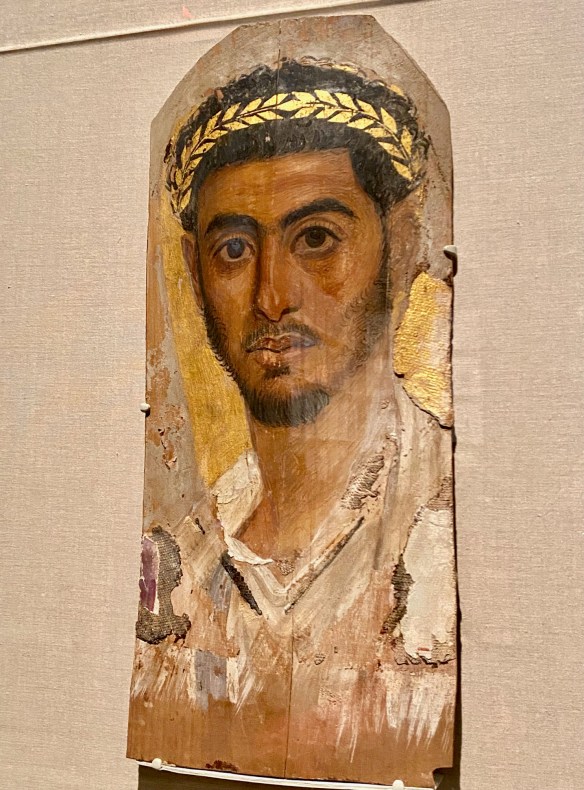

The Distinction section, for example, has a wall of impressive portraits and bedazzled swords of the first leaders of the Hatian revolution dressed in military finery – emphasizing their commitment to Englightenment ideals in the first successful slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere.

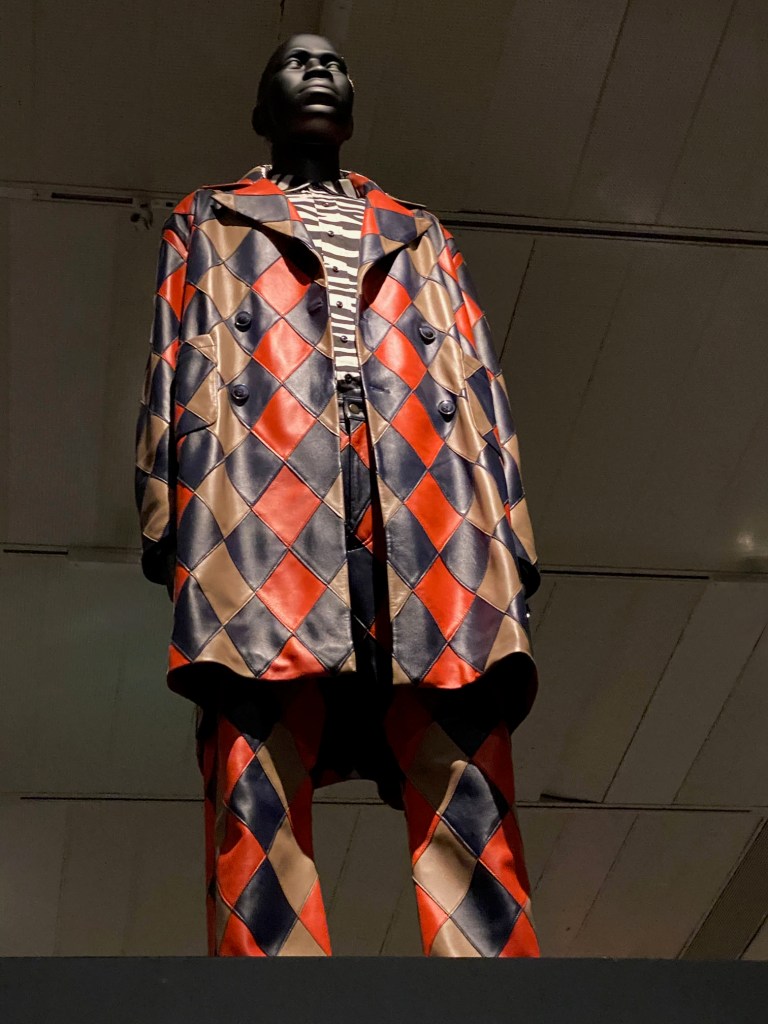

The brilliant multi-level exhibition design features contemporary menswear inspired by 18th-century revolutionary and military style, including a swaggering great coat designed for the ever-magnificent Vogue editor-at-large, Andre Leon Talley.

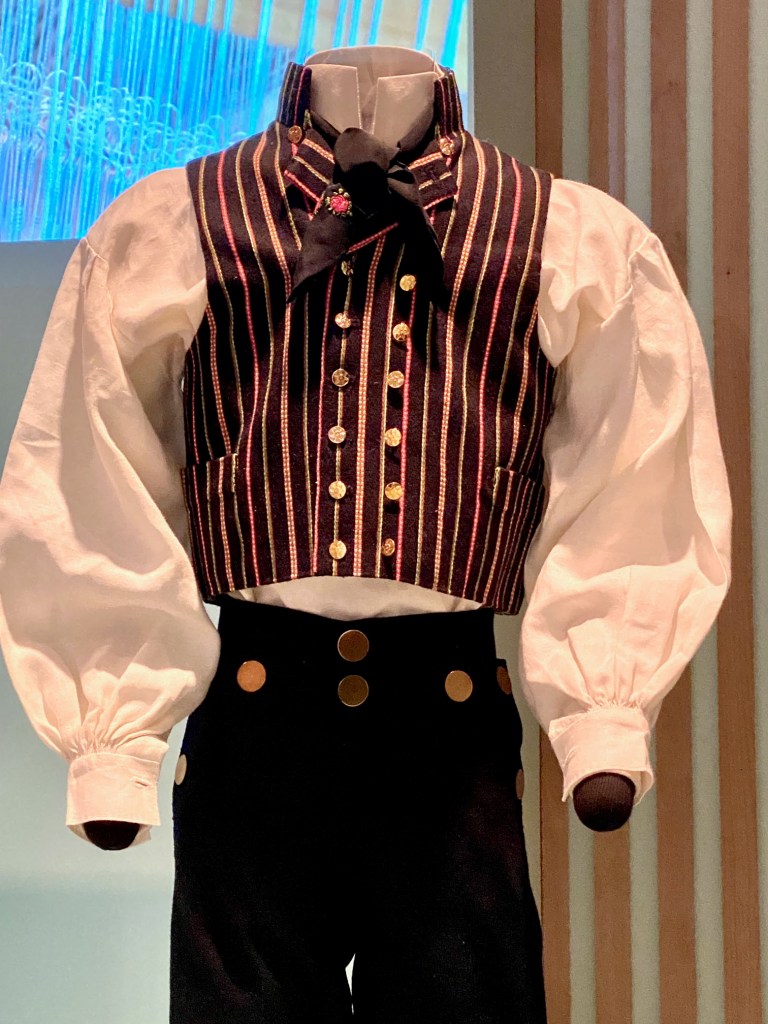

The Freedom section tells the story of the rise of the Black dandy in the 19th century and how the entrepreneurial class of African Americans dressed to impress. Historic portraits, photos, a fancy tailcoat, and a book on how to tie fancy neckwear – evidence of social upward mobility – are shown alongside cutting-edge contemporary menswear.

The Champions section focuses upon how successful Black athletes – such as Jack Johnson, Walt Frazier, and Mohammed Ali – used fine clothing and style to make a statement, and how althetic wear transitioned into upscale runway fashion.

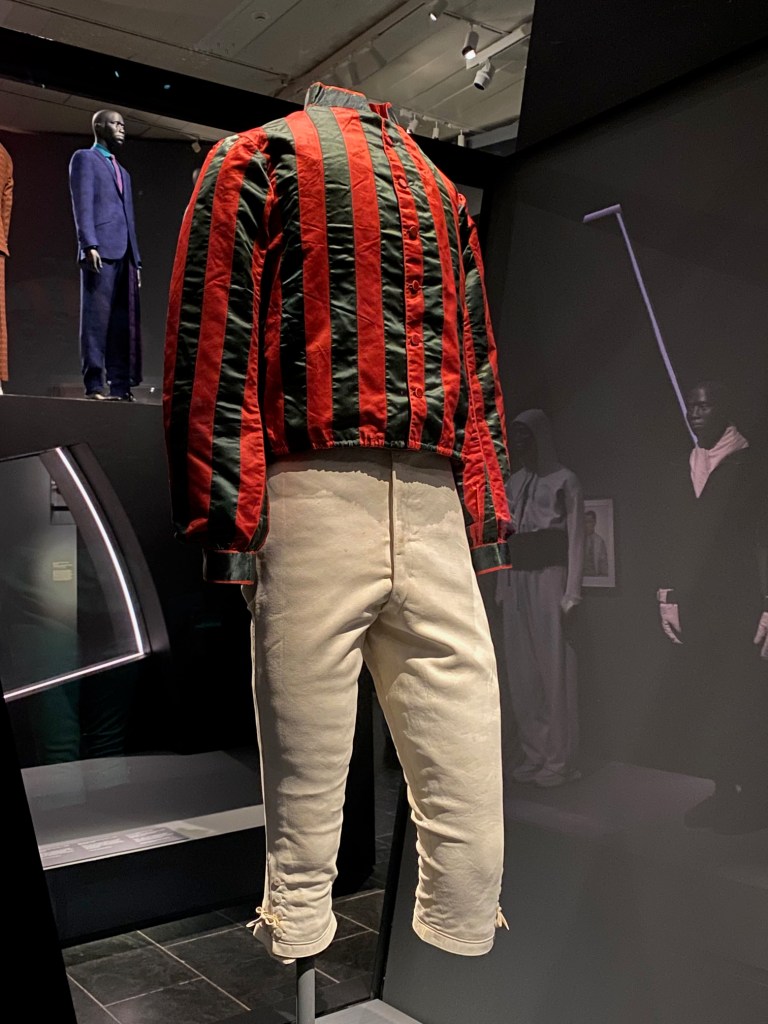

The story of Black jockeys is told – how 19th-century sports superstars got pushed out of early 20th-century racing when racial discrimination was at its peak, and how contemporary designers are incorporating this story into their designs.

The Respectability section explains how social-justice icons D.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass used their perfectionist style to draw a crown and make a statement, but it also discusses (and shows) the tools of the trade used by legions of Black tailors. There’s also a beautifully cut in-process example from Saville Row tailor Andrew Ramroop.

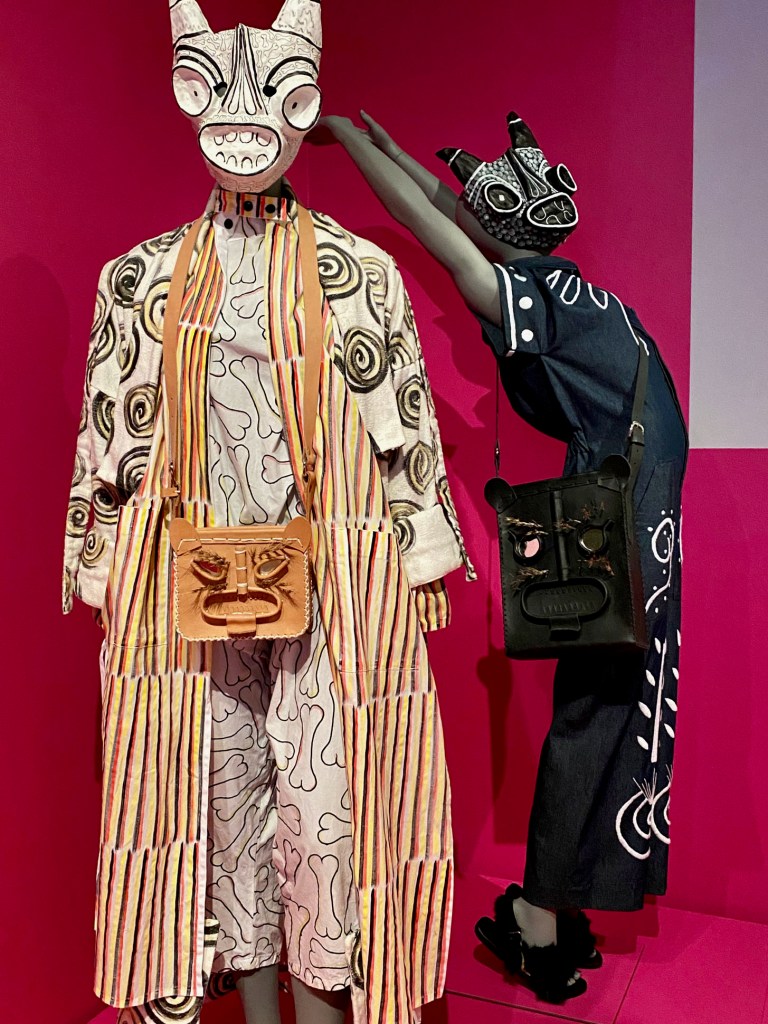

Of course, hip-hop takes its bow, too, with a tribute to Dapper Dan and other designers honoring the cool, ever-evolving style of Black musicians and performers.

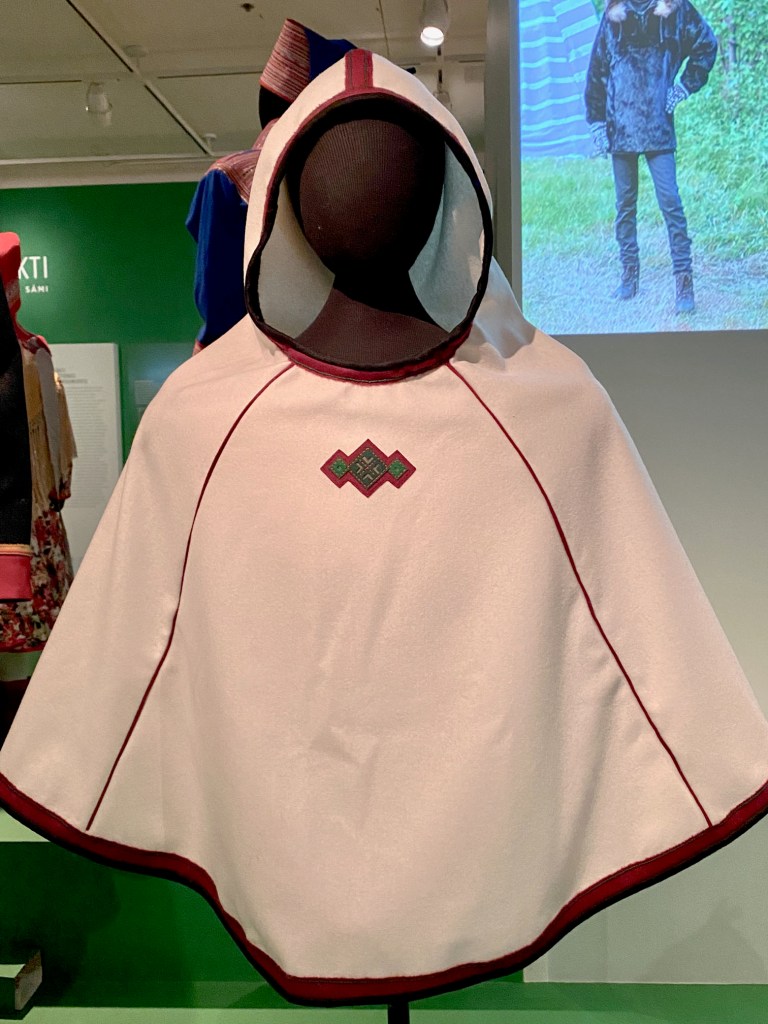

Take a look at some of our favorite features of the exhibit in our Flickr album – upwardly mobile campus-inspired fasion, zoot suits from the hep cats of the Forties, beautiful fashion flourishes flaunted by pop superstar Prince, and nods to African heritage.

For more, walk through this stunning, insightful, memorable exhibit with co-curators Monica Miller and Andrew Bolton: