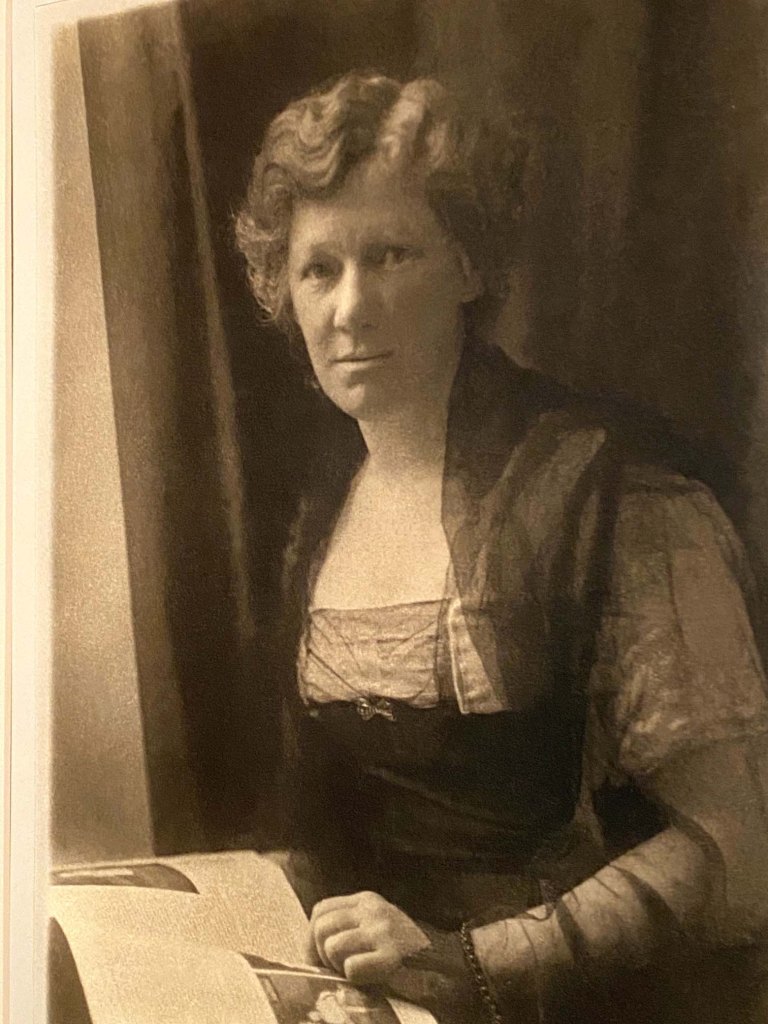

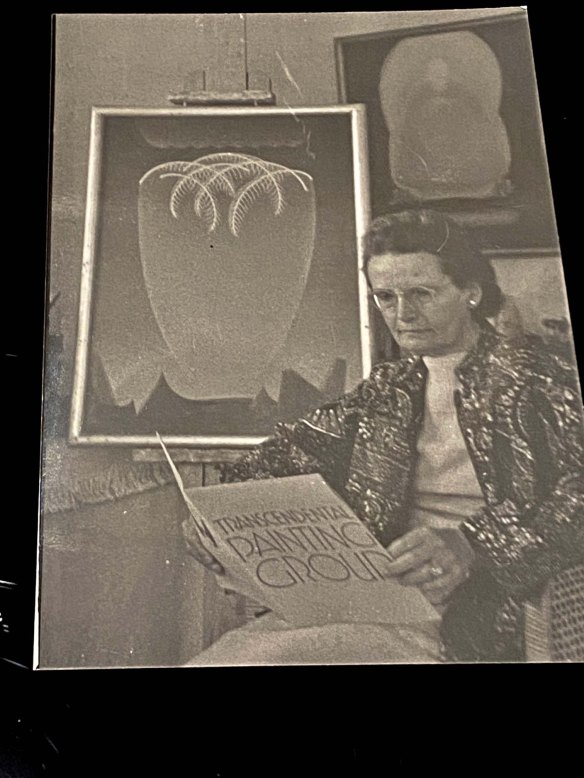

Do you wish you could travel back to Taos in the Thirties and Forties to experience the quiet, small, out-of-the-way place that inspired so many artists? Take a walk through this two-site exhibition, Legacy in Line: The Art of Gene Kloss, on view through June 8, 2025 at the Harwood Museum of Art and through May 31 at the Couse-Sharp Historic Site just off the Taos Plaza.

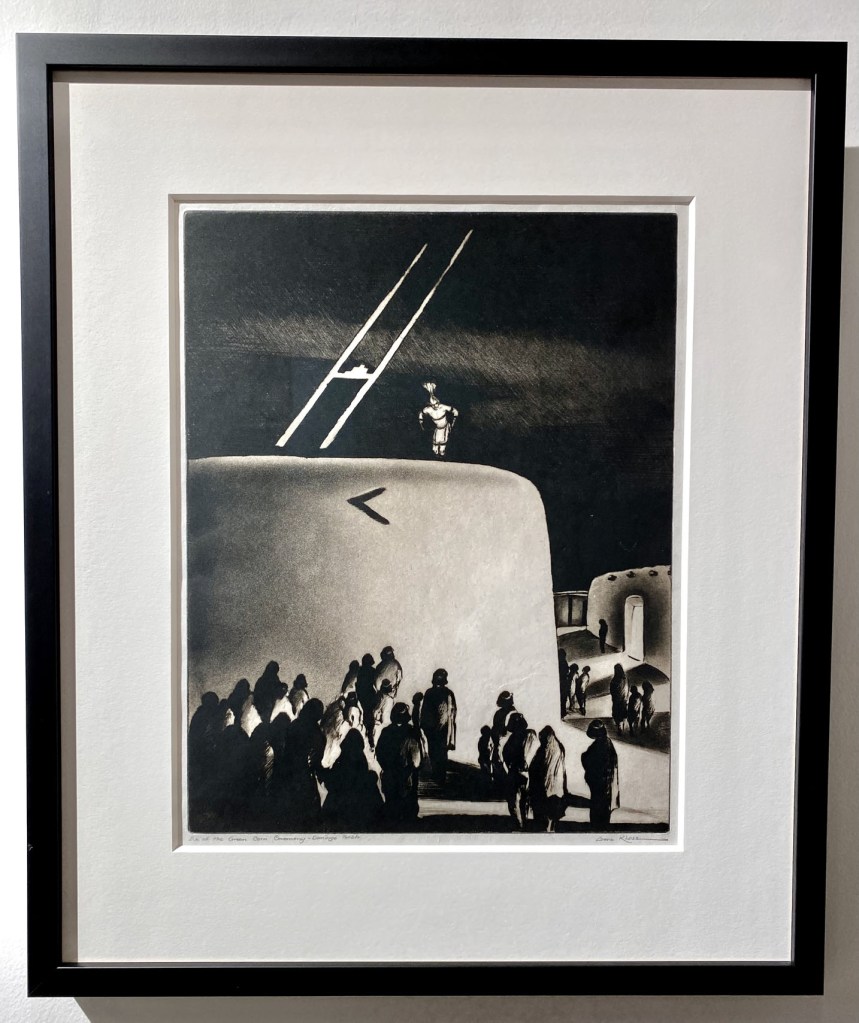

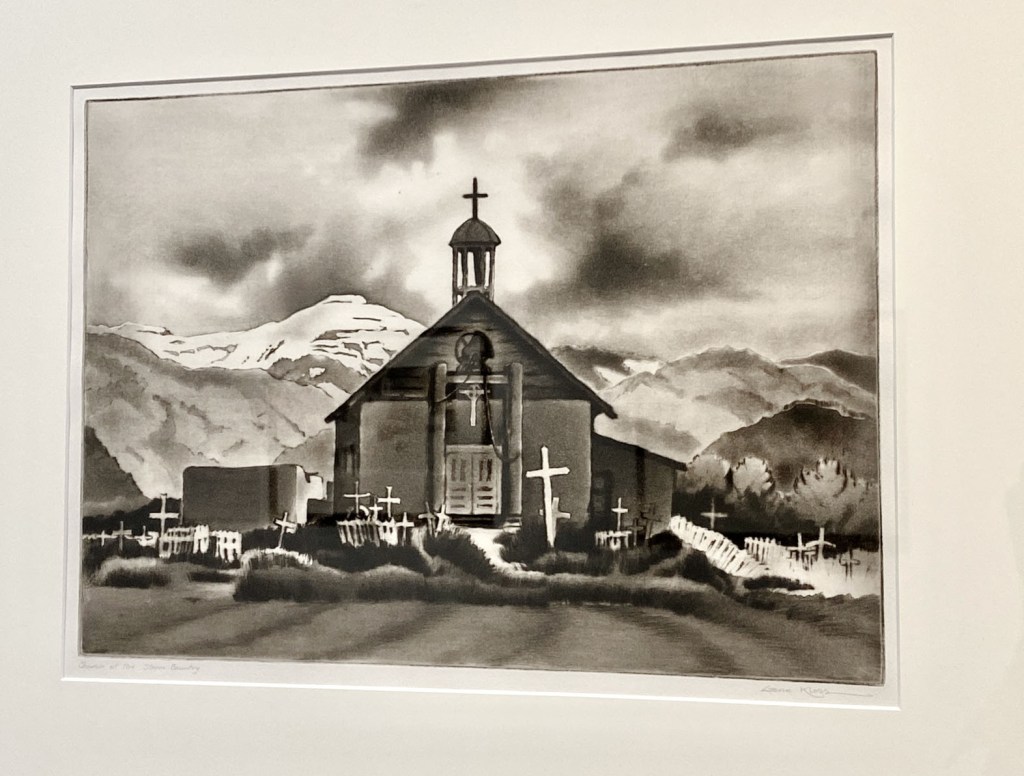

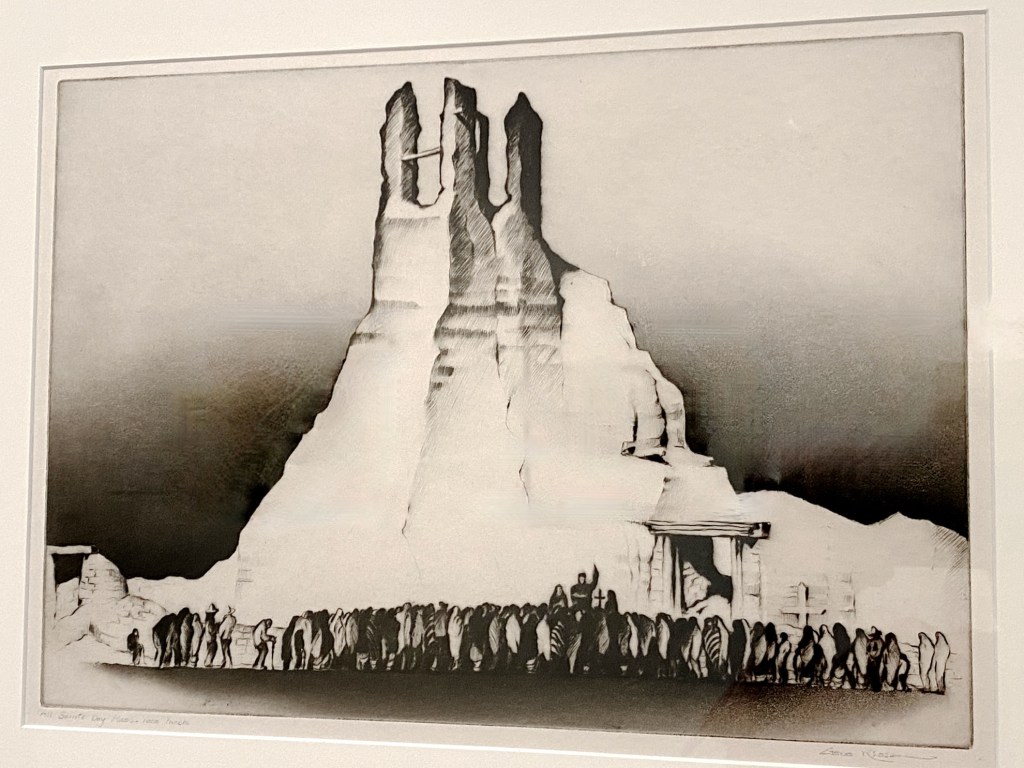

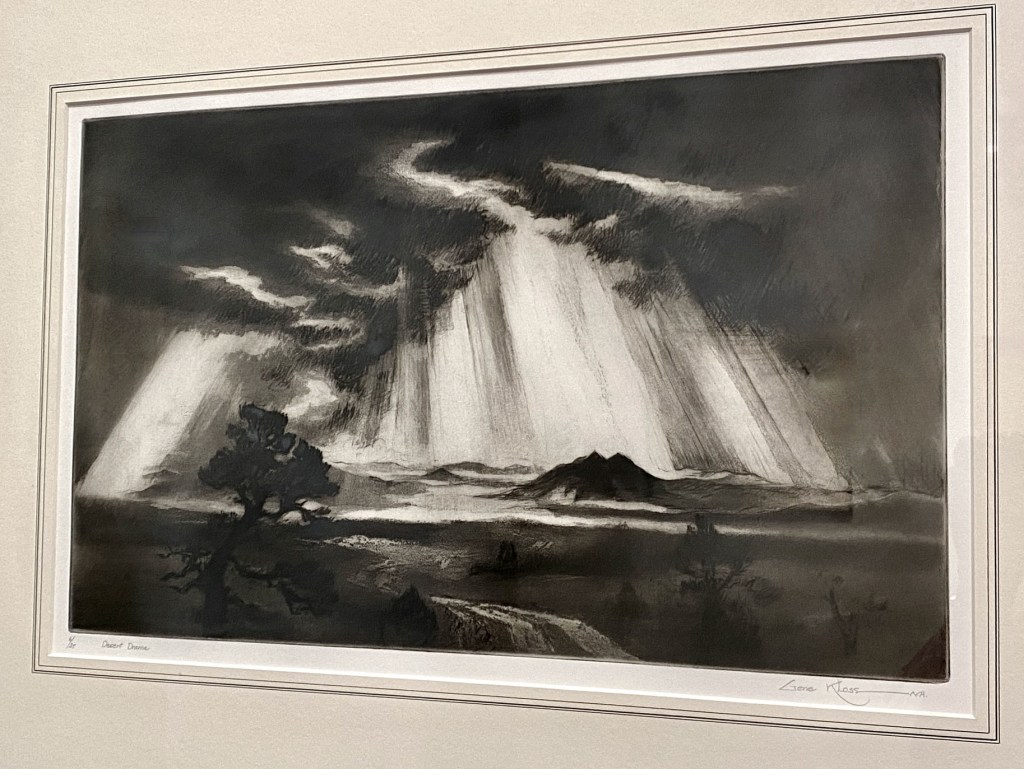

Kloss, whose artistic style was honed in the 1920s and 1930s, is arguably one of New Mexico’s favorite artists. Kloss specialized in printmaking, creating an immediately recognizable style – a landscape, village, or pueblo scene with dramatic contrasts (often at night). Look at some of our favorites in our Flickr album

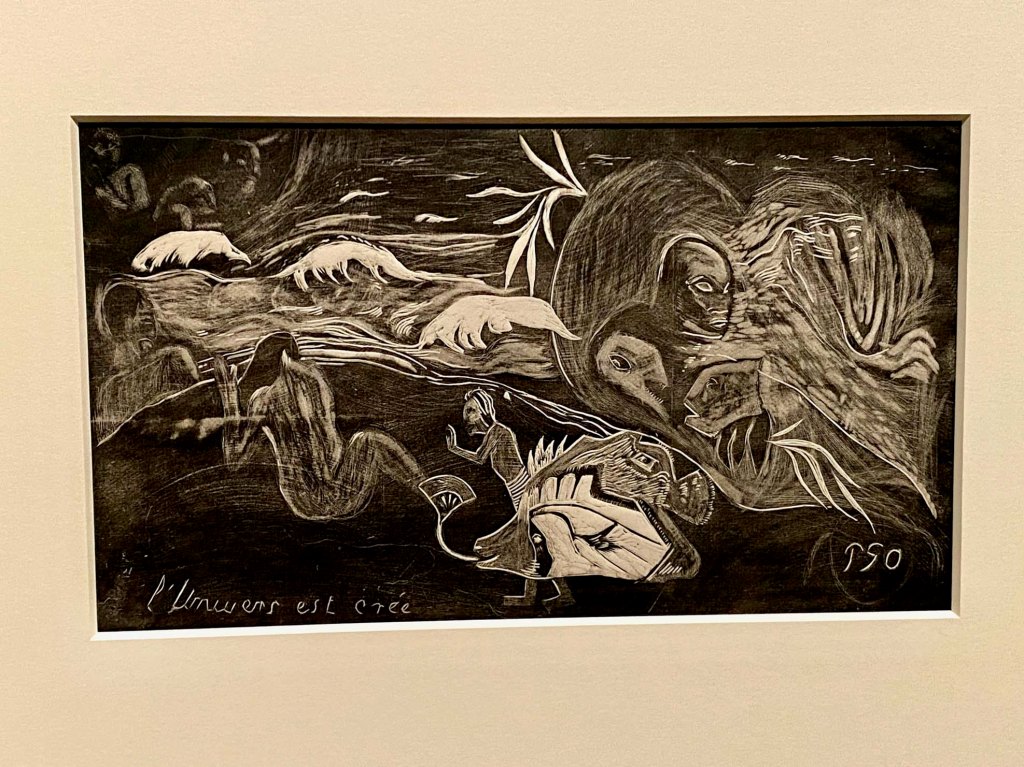

Kloss fell in love with plrintmaking as an undergraduate art student at UC-Berkeley. She was captivated by the printmaking revival that swept Paris and Britain in the mid-19th century. Artists owned their own presses and produced affordable prints of landscapes and small towns that encouraged everyone to collect art.

A lifelong resident of the Bay Area, she first came to Taos on a car-camping honeymoon in 1925 with her writer-composer husband. She fell in love with the landscape, the culture, and the pueblos of Northern New Mexico. Did I mention she brought along her 60-lb. portable printing press?

Kloss was prolific, and the next year showed over 100 of her paintings and prints – including Taos subjects – at a wildly successful solo show in Berkeley. She and her husband were hooked on the inspiration Taos provided, and soon rented a getaway home, where they would spend two to four months per year.

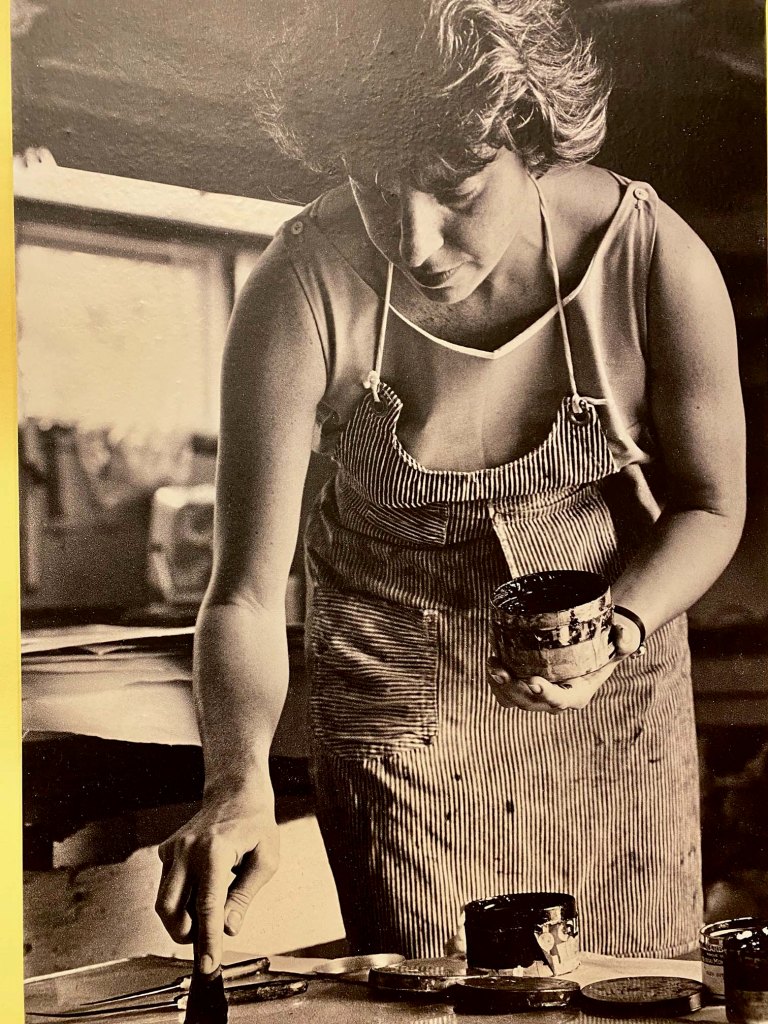

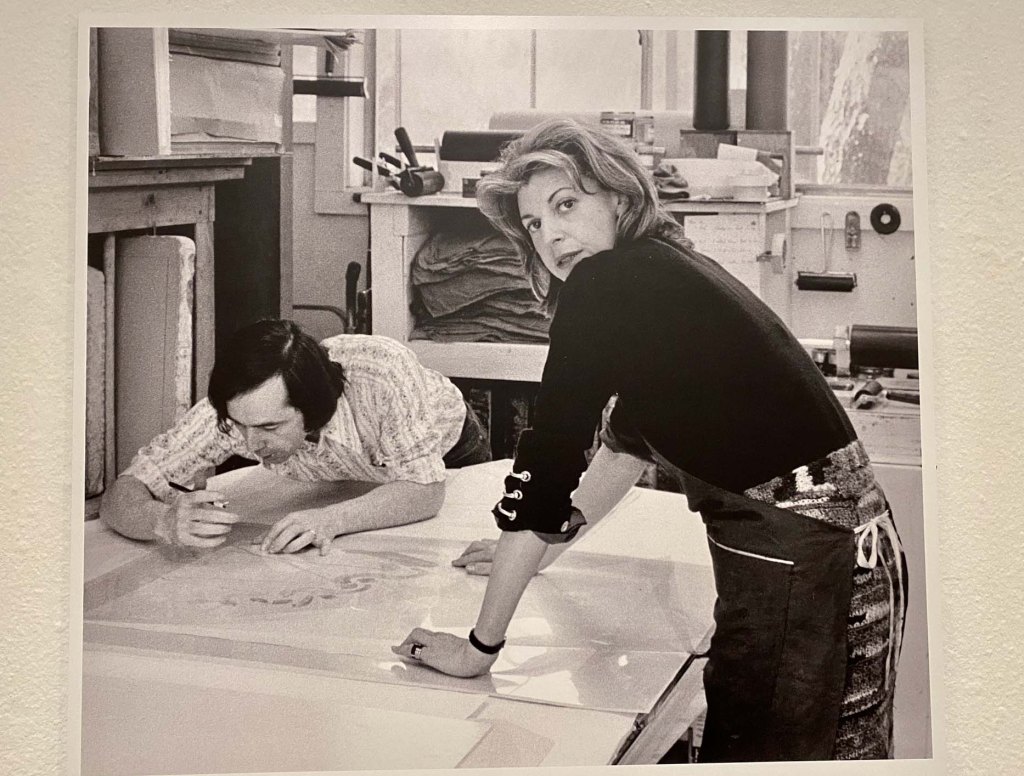

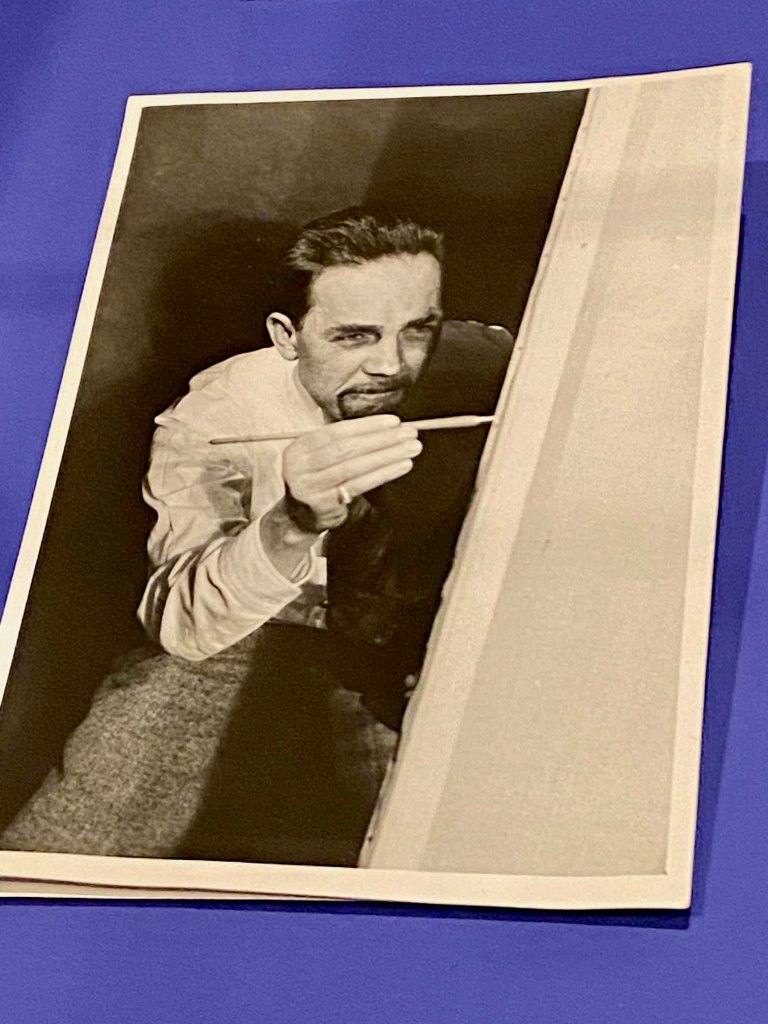

Kloss developed her images from quick sketches and from memory, bringing the drama as she precisely worked her impressions into the copper.

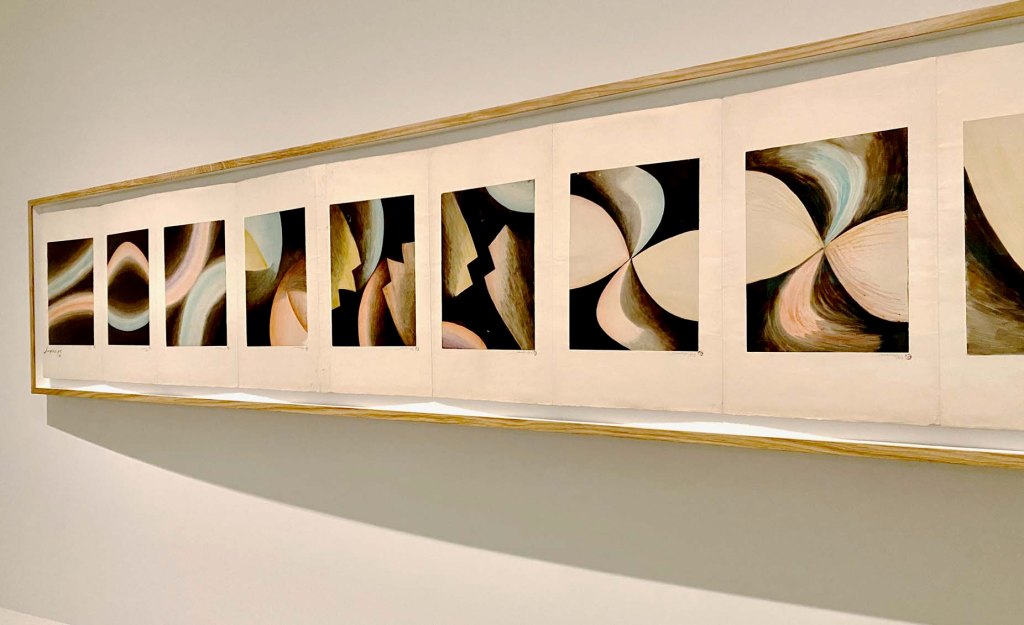

In the Thirties, Kloss did artwork under several New Deal programs and produced a nine-part series on New Mexico that was gifted to public schools in the state.

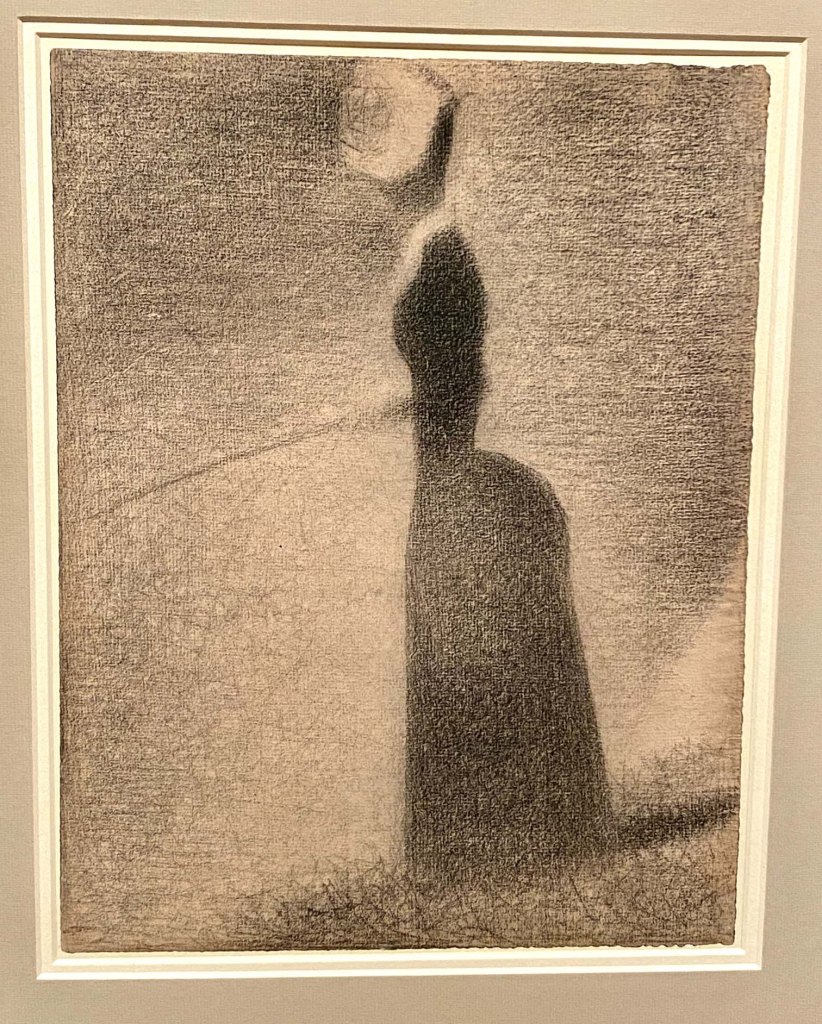

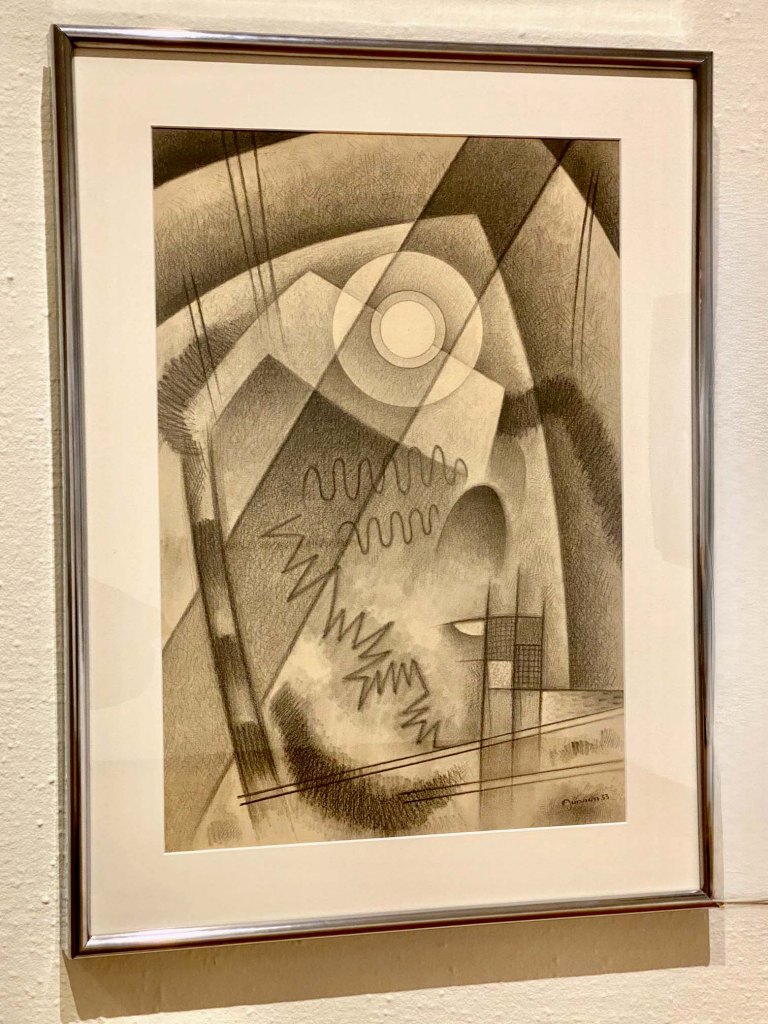

As a master of intaglio, drypoint, and aquatint, she developed an innovative technique in which she painted acid directly into the ground with a brush or pencil that allowed her to create super-deep tones, gradations, and atmospheres in her prints.

Few others could create scenes like hers – dramatic nighttime scenes at the pueblos, tiny pilgrims making their way at dusk among the mountains, or aerial views of old Spanish valleys.

Over her lifetime, Kloss would create over 18,000 signed prints, show in New York and Europe, and be honored with membership in the National Academy of Design. She always pulled her own prints in the studio, and kept on working through the Seventies, until the quality of commercial copper and ink that she had always used became unavailable.

The Couse-Sharp Historic Site (where the Taos Society of Artists was founded) and the Harwood Museum have mounted this fantastic show to honor a gift bestowed upon them by Joy and Frank Purcell, Taos residents and Kloss collectors that ultimately amassed over 130 of her works.

To see more of her work, watch this short New Mexico PBS documentary on Ms. Kloss with art historian David Witt, who talks about his friendship with her, her process, and unique interpretation of her Taos world: