The scale and scope of the contemporary art on display is tremendous, but how often do art-seekers also get an opportunity to travel across ancient streets and landscapes, to meet real and fictional historic characters, contemplate fables and real-life stories, and see art of the past and present side by side?

It can take days to experience and fully absorb all of the history and potential futues presented in the films, paintings, sculptures, and installations in Once Within a Time: 12th SITE Santa Fe International, on view across 15 art spaces across Santa Fe through January 12, 2026.

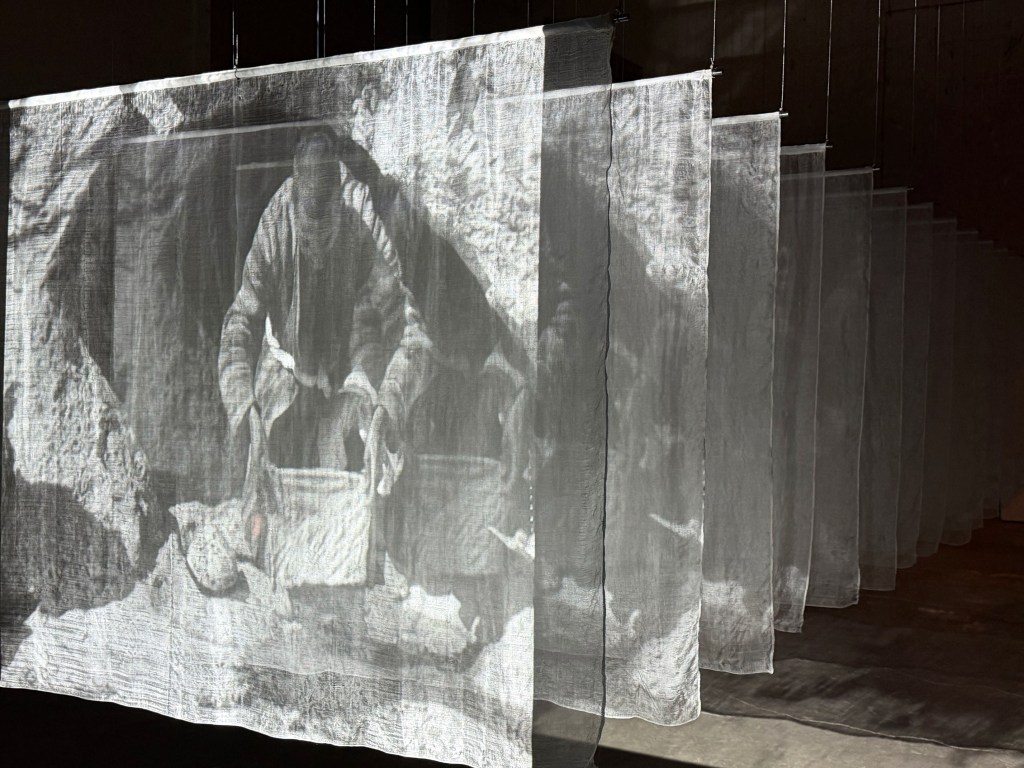

Besides the expansive white galleries and screening rooms of SITE’s museum in Santa Fe’s always-popping Railyard District, visitors can choose to contemplate giant abstract murals in a church-like auditorium, an innovative historical-object installation in a 400-year-old seat of power, or enter an old foundry to see an evocative installation by a Silk Road artist across farm fields adjacent to the Old Spanish Trail.

In every space and art encounter, visitors may reflect upon whether history is repeating itself and whether inspiration can be drawn from futures that artists imagined nearly a century ago. Each space is designed for visitors to look, read, encounter, and reflect.

The theme for the show – Once Within a Time – is inspired by Godfrey Reggio’s most recent film – a suggestive and wordless mix of innocence, nostalgic images, visual poetry, and the future facing the next generation. The film screens continuously inside SITE, with visitors caught up in Godfrey’s dream-like images, which highlighted in this mesmerizing movie trailer:

Like Godfrey’s film, each space and gallery presents a theme, story, historic character, and provocative contemporary art that pulls back in time, creates an unforgettable experience, and asks the viewer to go inward to contemplate the future.

SITE’s galleries, for example, present themes such as storytelling, technology and language, the power of spiritual energy, and New Mexico’s undeniable status as a natural Land of Enchantment.

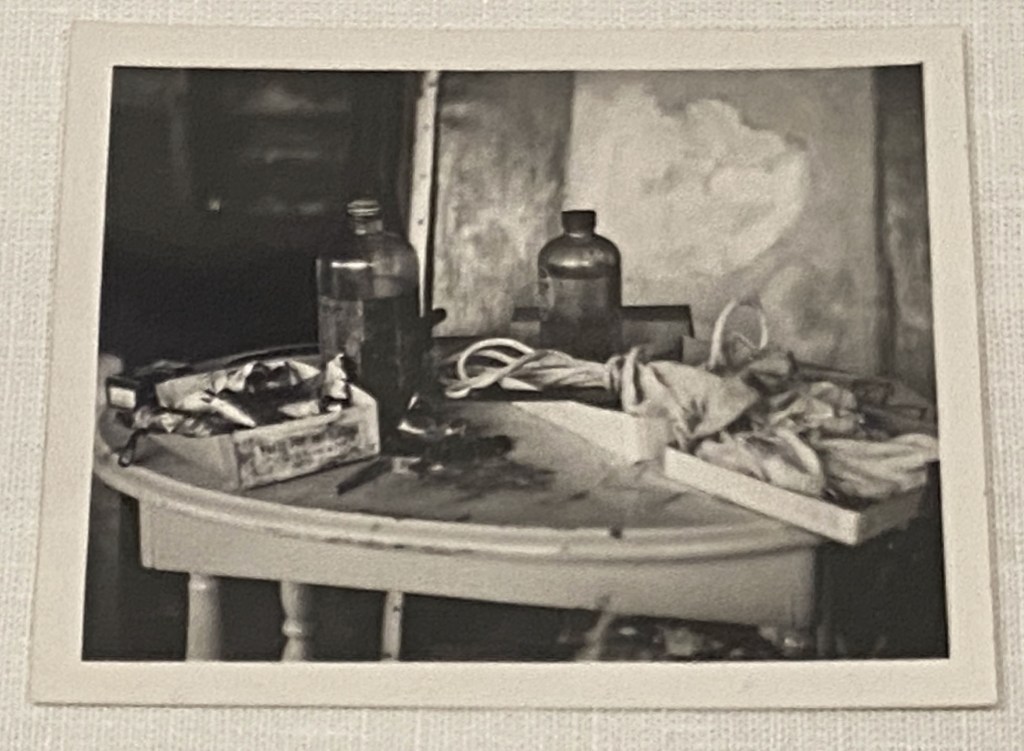

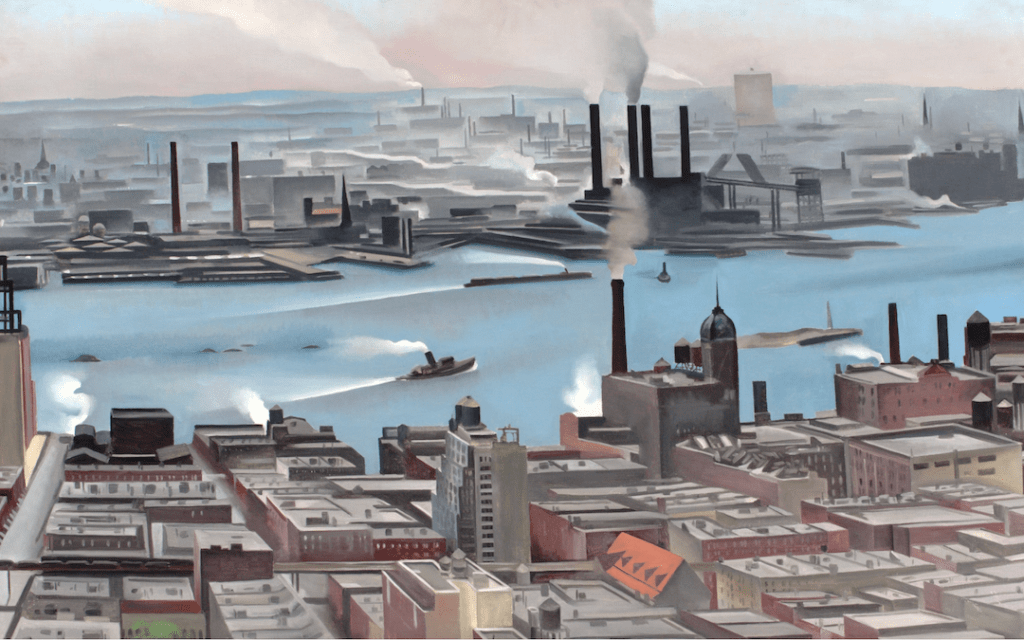

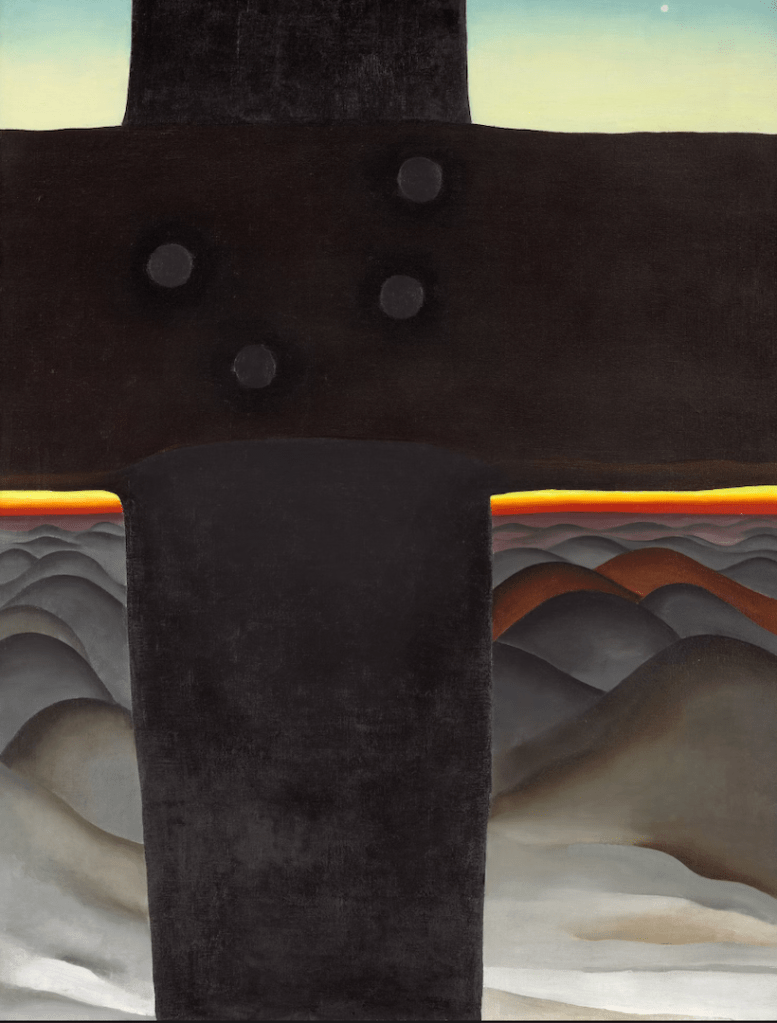

The exhibition presents traditional New Mexico superstars and inspirations – Awa Tsireh and Helen Cordero (San Ildefonso Pueblo), Agnes Pelton, Rebecca Salsbury James, Florence Miller Pierce, Pop Chalee (Taos), Pablita Velarde (Santa Clara Pueblo), and Eliot Porter – alongside artists who are breaking through on the international stage.

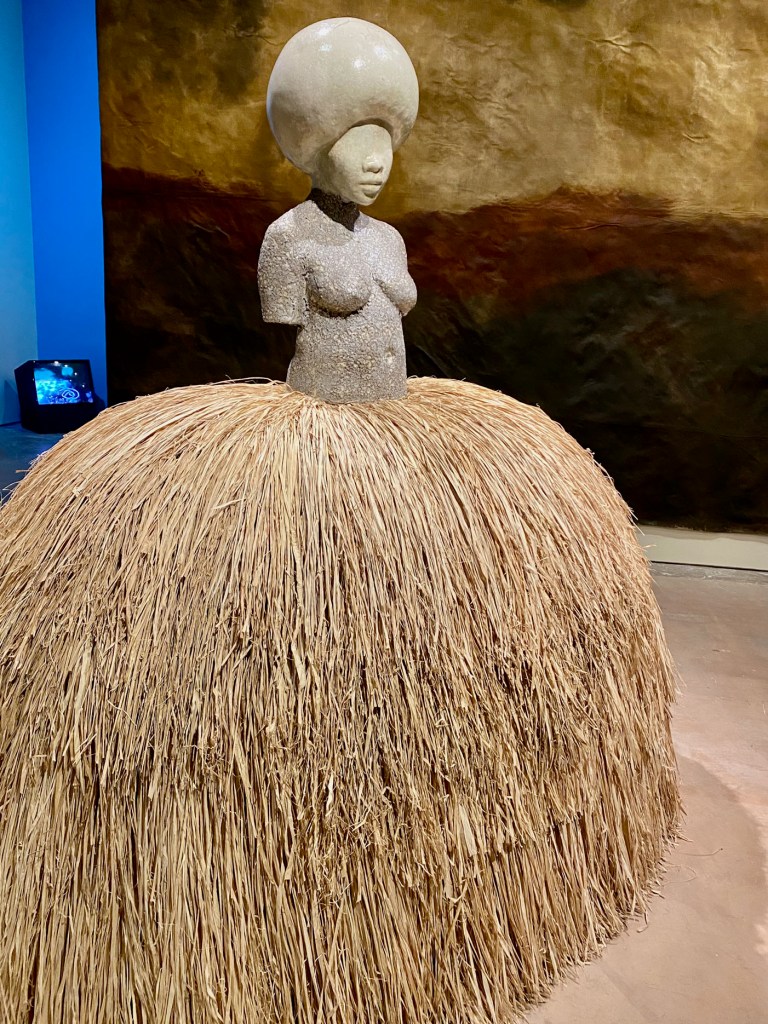

Cochiti pueblo ceramicist Helen Cordero’s storyteller figures are paired with Pablita Velardi’s storyteller illustrations (both are inspired by grandfathers and fathers) and Simone Leigh’s epic stone and raffia goddesses.

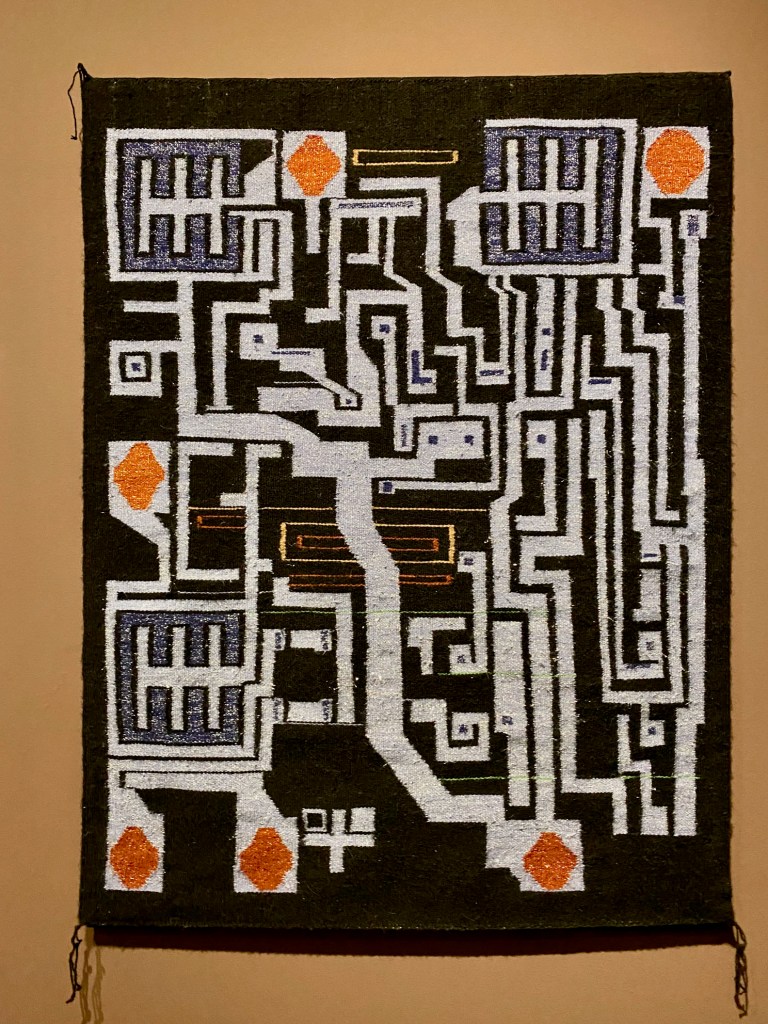

The story of the legendary WWII heroes, the Navajo Code Talkers, is featured in a gallery alongside Marilou Schultz’s weavings of chip technology using traditional Diné methods with Fred Hammersly’s ground-breaking IBM computer drawings at the University of New Mexico in 1968-1970.

Fred was given an opportunity to create the first mainframe-generated art in the form of drawings programmed by traditional IBM punch-card technology and the Art1 program. SIITE not only displays a selection of the 400 computer drawings that he generated over the course of 18 months, but some of the punch cards he used, which are now archived at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

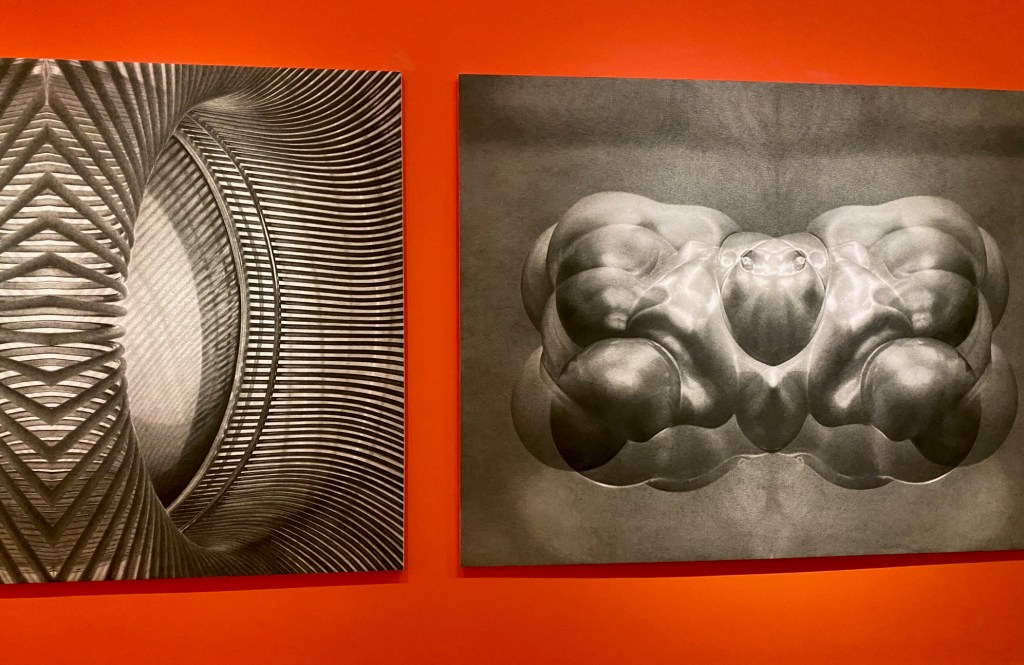

Sensual free-thinkers are represented by the story of Santa Fe gambling mogul Doña Tules (Maria Gertrudis Barceló) and her actual 1840s money chest, witty contemporary porcelain playing cards and magical paintings by Katja Seib (UK), and jaw-dropping drawings by Shanghai’s Zhang Yunyao.

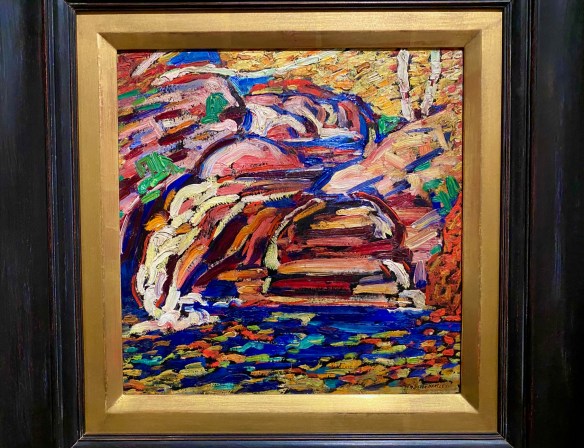

Around the corner from Agnes Pelton’s transcendental paintings are Diego Medina’s landscapes reflecting the Piro-Mansa-Tiwa spiritual power inhabiting ancestral lands of Southern New Mexico and also installations about a different type of New Mexico light – the impact of the nuclear energy tests on people living downwind and the legacy of uranium mining across native lands.

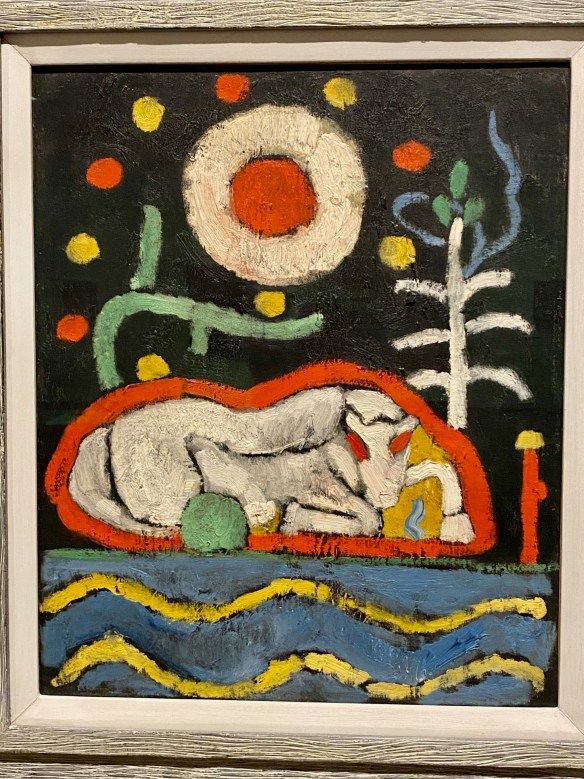

New Mexico’s natural world is paid tribute in stories and artwork by travelers and residents – watercolors of Pueblo spirits and wildlife by Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal) in the 1930s, Vladimir Nabokov’s sketches of butterfly wing cells (1940s-1950s), and Eliot Porter’s spectacular photos of Tesuque jays in the 1960s.

But these examples are just snippets of Once Within a Time – the entire show deserves multiple visits, and time to visit the other locations in the city, such as the hidden basement natural wonderland epic at the Museum of Internatonal Folk Art created by Taiwan ‘s Zhang Xu Zhan. It’s not only an immersive environment, but a film, animal-spirit sculptures, and selections from the MoIFA’s paper funerary object collection. Don’t miss the Day of the Dead altar, the 18th-century Pere Lachaise Cemetary tribute initially collected by Mr. Girard himself, and paper funerary fantasies made by the artist’s own family. Truly unforgettable.

The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian fills the Klah Gallery (in the shape of a traditional hogan) with a meditation on healing by Cristina Flores Pescorán, a wild organic sculpture by Nora Naranjo Morse, and a mini-retrospective of paintings by the incomparable Emmi Whitehorse.

The Tesuque location also features rooms with installations by Mexico’s Guillermo Galindo incorporating burned wood from the recent New Mexico fires (crossed with Picasso’s Guernica), David Horvitz’s tribute to the men incarcerated in Santa Fe’s Japanese internment camp (and a hat from one them), and Thailand’s Korakrit Arunanondchai’s room-sized contemplation that incorporates the ashes from the burning of Zozobra.

For more, take a walk through the main exhibit and five other sites in and around Santa in our Flickr album to see work by legendary New Mexican artists, and travel back and forth to see how contemporary art reflects epic histories and mystic systems of the Southwest.