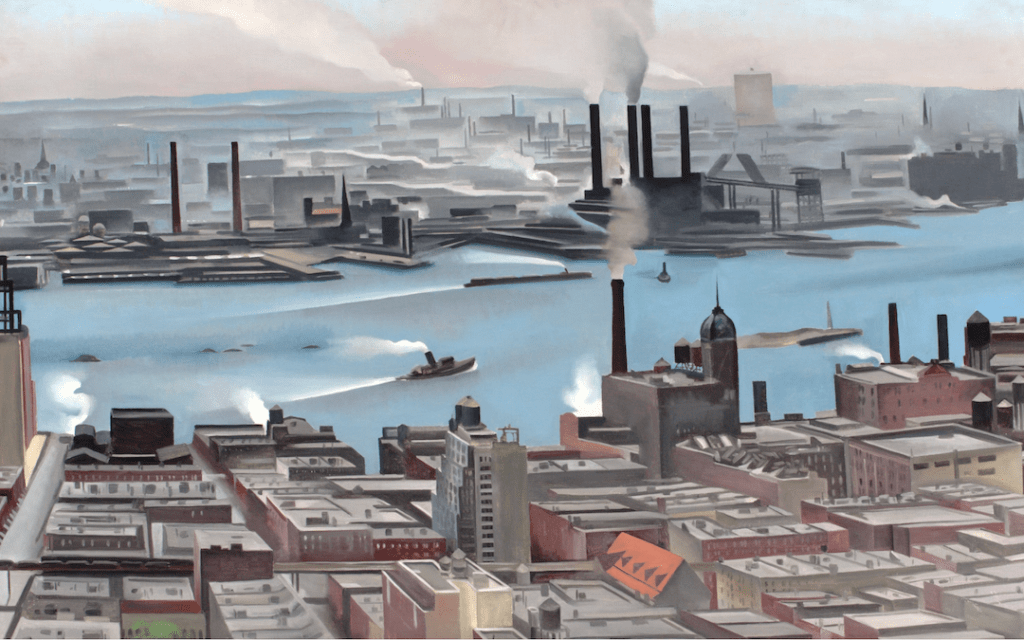

Fans have had a special opportunity to get up close to that iconic black dress and gaucho hat, OK Calder pin, denim apron, and Marimekko dress in Georgia O’Keeffe: Making a Life, on view in Santa Fe through October 19 2025 at the O’Keeffe Museum.

After you’ve walked through a somewhat chronological presentation of Ms. O’Keeffe’s paintings in the museum, the final two galleries allow you to take a close-up look at tools, cookbooks, and other stuff that she used to make things – sculpture, recipes, pastels, and clay pots.

Due to the overwhelming popular response to Living Modern, the traveling exhibition that featured O’Keeffe’s wardrobe and chronicled how she portrayed herself for the greatest photographers of the 20th century, the museum curators decided to give visitors a little taste of the woman behind the art.

See some of our favorite things in our Flickr album here, and listen to the museum’s audio guide here.

It’s the first time that the O’Keeffee Museum has itself presented her clothing. To emphasize the “making” part of her life in New Mexico, they’ve included a case showing how Santa Fe artist Carol Sarkasian moonlighted as Georgia’s seamstress. There’s a case with sewing notions and cut pattern pieces for another version of Georgia’s always in-style black wrap dress. She totally believed in multiples!

She also believed in wearing her clothes for a long time, and so they showed they had years of life.

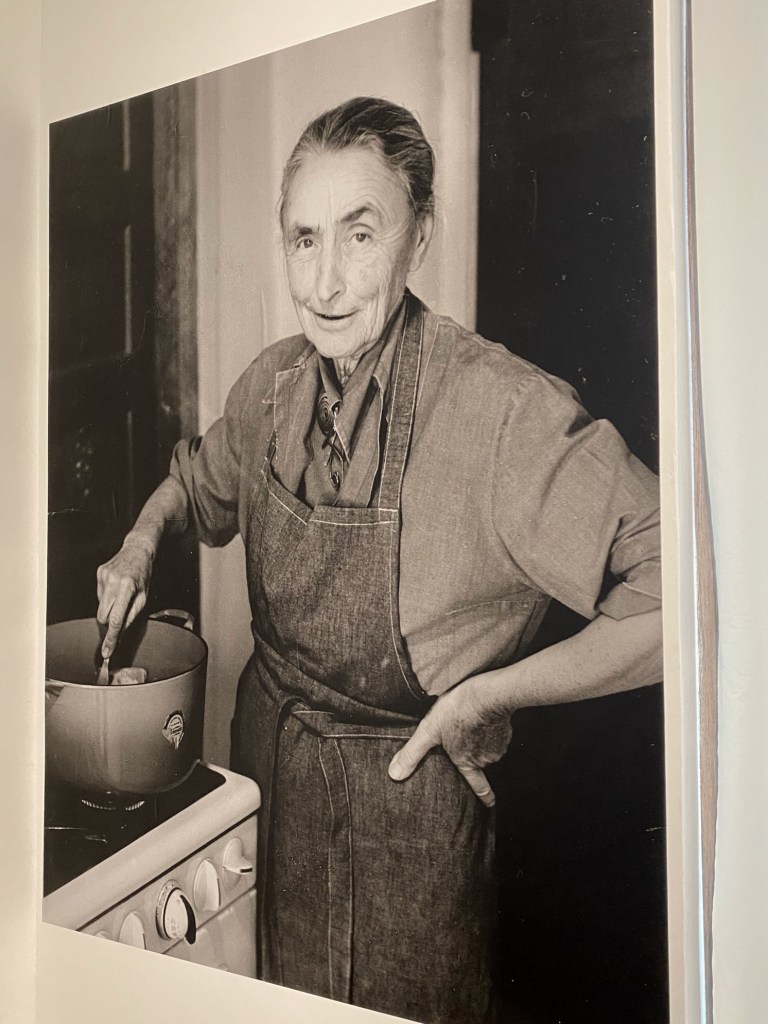

The most popular feature of her Abiquiu home tour is the kitchen and pantry, and learn about Georgia’s farm-to-table approach with her garden, recipies, and day-to-day lifestyle. Here, you get a glimpse of the modern and traditional appliances used for her daily coffee ritual (yes, she loved Bustelo!) and get to peruse a sampling of her cookbooks and hand-written recipies.

One of her unrealized dreams was to write a cookbook, and it shows. She was all about healthy eating and living, and in her later years she relied upon her trusted Abiquiu team to assist with gardening, cooking, and putting out a spread for the constant stream of visitors. (No recluse, she!)

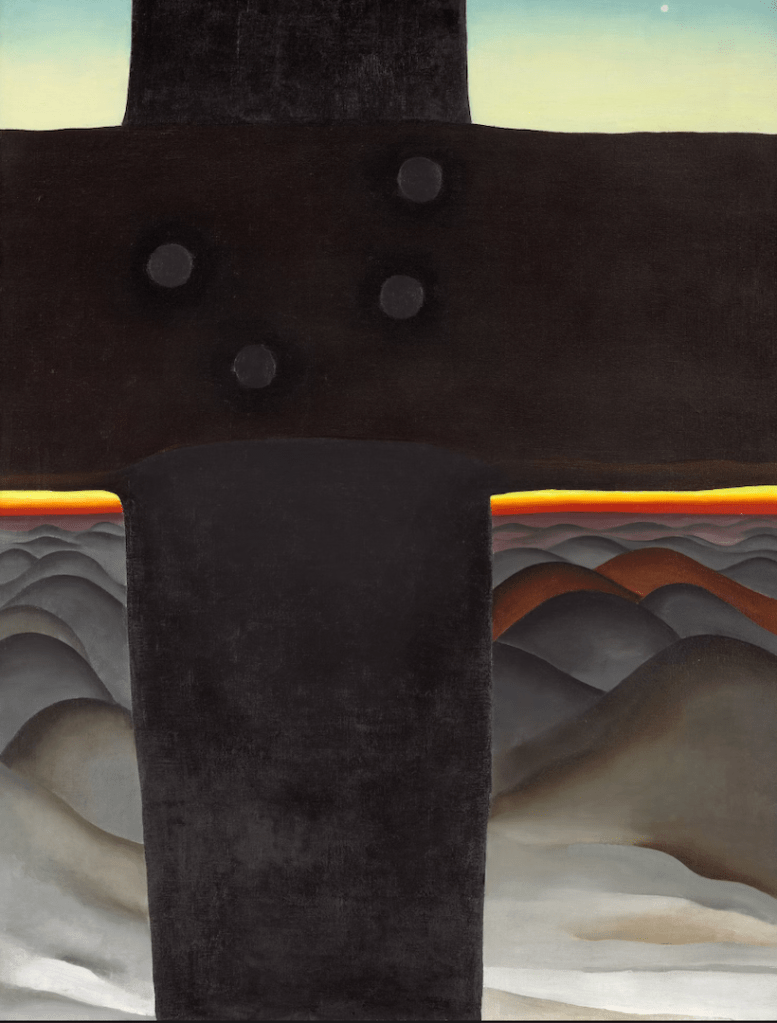

The final room shows the process and tools she used to create her paintings, pastels, and sculptures.

There’s a dramatic photomural of Georgia standing in front of her largest sculpture – temporarily housed nearby at the New Mexico Museum of Art until the new GOK museum is built. Beneath, you see several prototypes – a wax spiral made in 1916 and bronze maquettes from the Forties.

Cast when she was in her nineties, the case demonstrates that she kept making versions of this her whole life and finding inspiration from stuff found on her New Mexico wanderings.

There are things from her travels to Japan, an unfinished work on an easel, and a case showing the pot she made when her assistant, Juan Hamilton, convinced her to keep making shapes, even when her macular degeneration made it impossible for her to paint.

The round, smooth shape echoes the rocks that she liked to collect, so it’s fitting that the museum paired her tools and pot with a beautiful oil painting done of one of her favorites.

For more on Georgia and her life, listen to Pita Lopez, who worked as a companion and secretary for Miss O’Keeffee from 1974 to 1986 and later oversaw maintenance and preservation of her Abiquiu and Ghost Ranch homes.