The first-ever adult Night at the Museum sleepover at the American Museum of Natural History last night was a hit, thanks to the enthusiasm and star power of Dr. Mark Siddall, the curator of the fantastic exhibition, The Power of Poison, closing August 10.

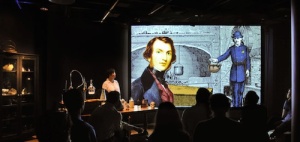

Early in the evening, Siddall mingled with sleepover guests at dinner in the Powerhouse and later in a series late-night talks from the Victorian theater inside the Poison show where costumed performers normally show visitors how to gather clues to solve a period murder mystery involving poison. (Think “I’ve got poison in my pocket” from A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder.)

After dinner, the adventurers, some in costumes themselves, made quick trips with their stuffed animals to the cots under the Blue Whale and bounded up the stairs through the low-light galleries to reach the shark IMAX, live animal demos, fossil tours, and Siddall’s Poison briefings.

You had to pass through the always eerie Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians (hello, Komodo dragons!) to enter the magical kingdom of the Poison galleries.

Once inside, you were transported to a tropical rainforest, with golden poison-dart frogs under a dome, huge models of dangerous insects, and a toxin-eating Howler Monkey lurking on a branch.

Beyond the tropics, the show morphed into a land of make-believe…or was it? Tableaux with a sleeping Snow White, the witches of Macbeth, and the Mad Hatter were captivating, with the label copy bringing you back down to earth by explaining the role played by poisons and toxins in these scenes and what exactly witches’ brew contained.

A Chinese emperor (the one with the terra cotta army, no less!) ingests mercury in one diorama, thinking it’s going to give him immortality. Wrong move. Glancing down, you find out that as recently as 1948, mercury-laced teething powder was still being used on babies in the United States.

A spectacular illusion along the way is a magical set of Greek vases whose painted figures came to life to tell stories of how poison helped Hercules and doomed Ms. Medea.

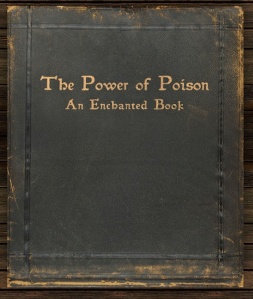

The lively vases are a prelude to the exhibition team’s greatest wonder – the Enchanted Book – a gigantic tome where ancient illustrations leap to life as you turn big, think parchment pages. Visitors could not get enough of that magic book. Somehow the AMNH digital team replicated it on the website, so click here to take a look at The Power of Poison: An Enchanted Book and turn the pages on line.

The lively vases are a prelude to the exhibition team’s greatest wonder – the Enchanted Book – a gigantic tome where ancient illustrations leap to life as you turn big, think parchment pages. Visitors could not get enough of that magic book. Somehow the AMNH digital team replicated it on the website, so click here to take a look at The Power of Poison: An Enchanted Book and turn the pages on line.

Here’s a glimpse of one story from the belladonna page, providing the backstory on how witches fly:

A lot of Siddall’s spectacular, magical, immersive, theatrical exhibition explains the science behind venoms, the “arms races” in the natural world, poison’s role in children’s stories, and how to analyze clues in solving murder mysteries.

Check out the Victorian-style introduction to Poison with Dr. Mark Siddall, its creator, and get a little taste of what the sleepover guests saw and heard.

To ward off any bad dreams about toxins or creepy crawlers, a lot of the late-nighters nestled in to watch vintage Abbott and Costello and Superman films and post Instagrams from the cozy, pillow-lined pit in center of the Hall of Planet Earth.

See the Today show’s recap (video after the commercial).

PS: If you can’t get to this show before August 10, download the iPad app, Power of Poison: Be a Detective that allows you to experience the last portion of the show. It’s been nominated for a 2014 Webby Award in the Education and Reference category.