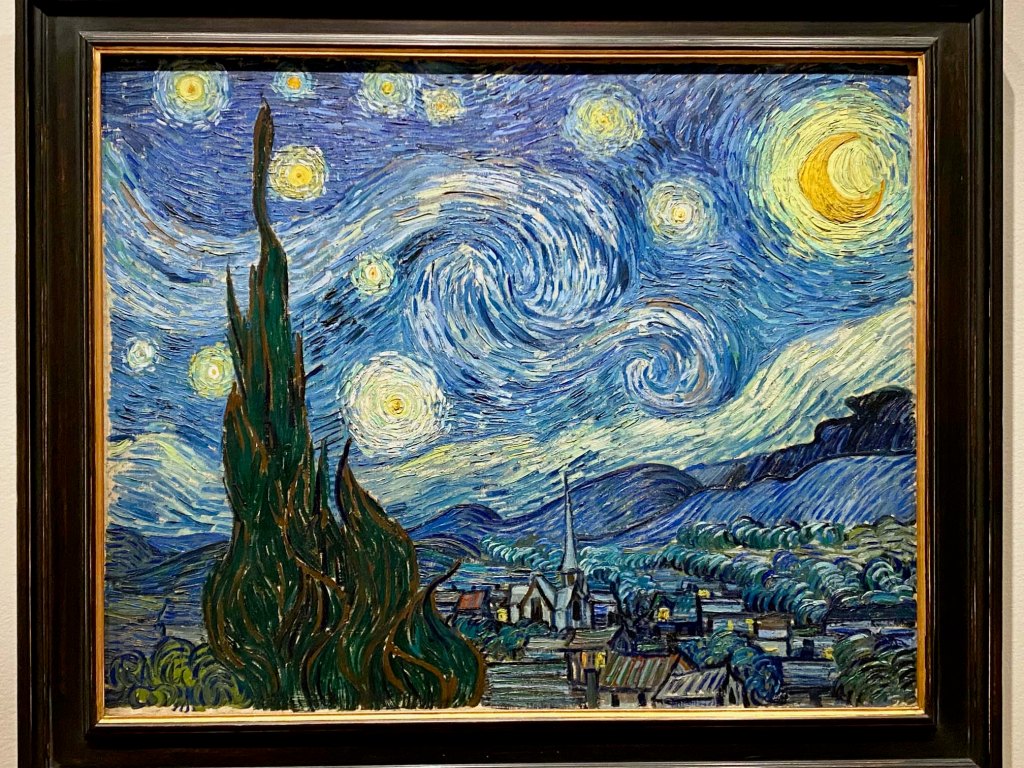

When you peek into the second-floor MoMA exhibition, you’ll see where Van Gogh’s The Starry Night has been holding court for the last few months.

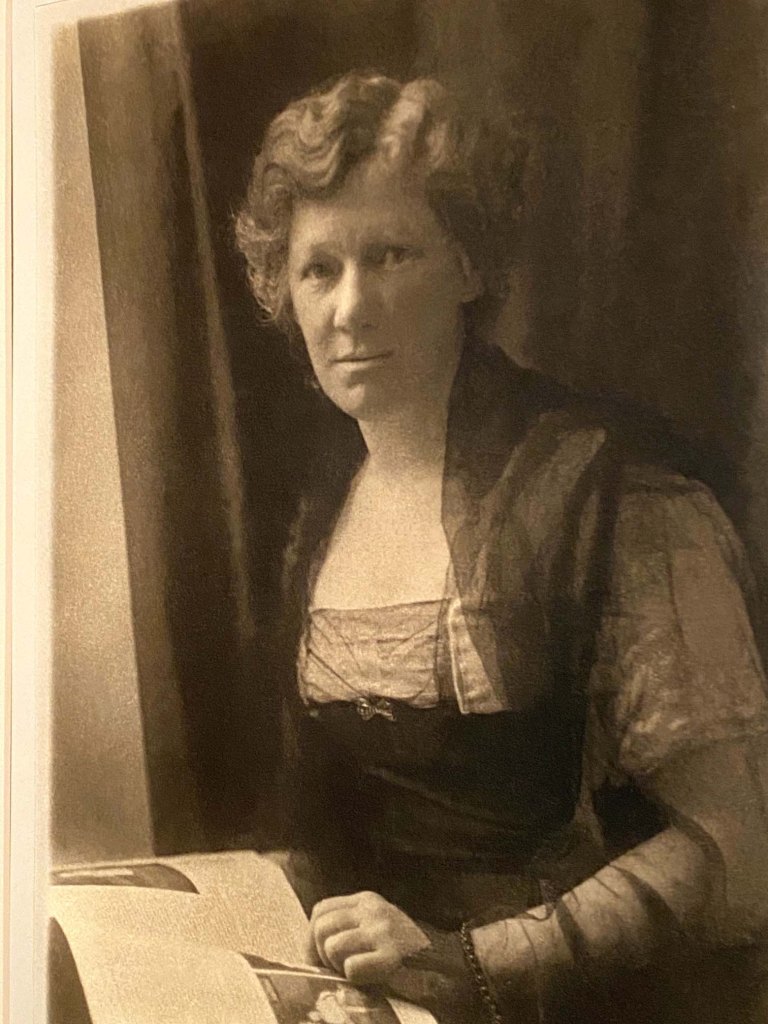

Lillie P. Bliss and the Birth of the Modern, on view through March 29, tells the story of how one woman’s passion for modern art over a century ago formed the basis of the MoMA collection and MoMA itself.

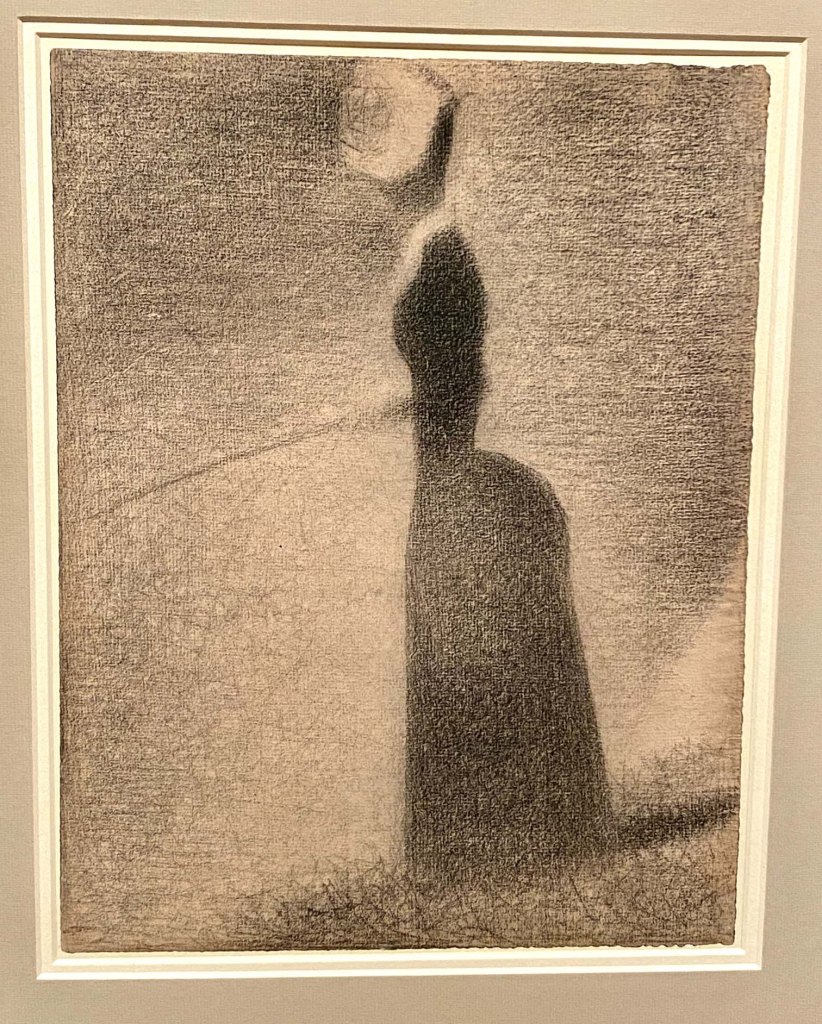

Bliss was an early American patron of Cézanne, Seurat, Picasso, and Redon at a time when New York society looked askance at modern art’s tilted tables, fractured still lifes, and stippled surfaces. She even contributed to getting the 1913 Armory Show off the ground as a sponsor, art lender, daily visitor, and new-work buyer.

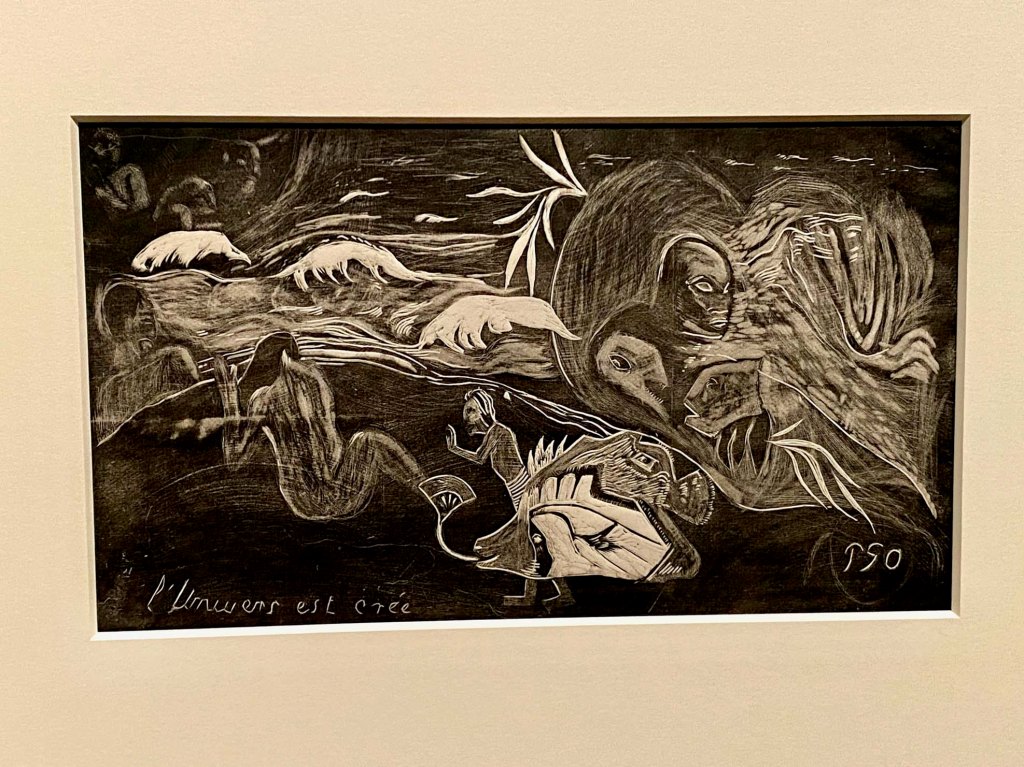

Maybe the constraints of growing up female in the Victorian era gave her an appreciation for the lack of inhibition Picasso’s and Matisse’s colors, Gauguin’s wild Tahitian woodcuts, and Redon’s ethereal woodsy fantasy figures.

Endless modern-art discussions with art-world friends and mentors Arthur Davies and John Quinn gave her a sophisticated view of all the latest artists and trends. She joined a small group of modern-art lovers to lobby the Metropolitan Museum of Art to show the latest breakthroughs from Europe.

In 1921, the Met acquiesced and borrowed enough art to mount an exhibition of French impressionist and post-impressionist work. Bliss anonymously lent twelve pieces. People came to look, but the Met still resisted acquiring work that it considered too far-out.

When Bliss came into her inheritance in 1923, the pursestrings were unleashed. At age 49, she began to assemble the collection of her dreams via annual European buying trips and estate sales. Where could she show it?

In 1928, she bought a lavish uptown triplex with a two-story gallery. She hung her favorite Cezanne over the grand piano and arranged a “who’s who” of avant-garde masters. Check out The Bather front and center, surrounded by Picassos, Seurats, and Gauguins.

The next year in a brainstorming session with Abby Rockefeller and Elizabeth Parkinson, the trio decided that New York needed a special place that was devoted exclusively to modern art. MoMA was born!

MoMA’s first exhibition – Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, van Gogh – was mounted in rented space at 730 Fifth Avenue, and crowds came. The exhibition was a huge popular success, even though it coincided with the historic 1929 market crash.

Lillie’s health crashed, too. On the heels of MoMA’s test run, she was diagnosed with cancer, and started drawing up a will to ensure that her beloved collection would carry on when she could not. She gave a Monet and a few gems to the Met, but bequeathed 150 works to the new Museum of Modern Art – forming the core of the collection we know today.

When Lillie died in 1931 at age 66, there was only one last thing. She was never able to acquire a Van Gogh. But in her will, she did give the museum permission to sell or exchange most of the paintings she bequeathed.

A few years later, MoMA sold one of Lillie’s Degas to acquire Picasso’s epic Demoiselles d’Avignon.

And in 1941, Alfred Barr made her dream come true. He heard that a dealer possessed a very special Van Gogh, and traded three of Lillie’s paintings for The Starry Night.

See our favorite works in our Flickr album, and enjoy other stories about this visionary MoMA founder by listening to the audio guide for the exhibition here.