Ascending the ramp inside the Guggenheim Museum to enjoy Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910-1930, European optimism and color abound. The exhibition, on view through March 9, 2025, showcases the exuberance and innovation of artists living in early 20th century Paris, who felt exhilarated by the profusion of modern forms of music, dance, and architecture and used abstraction and prismatic color to translated their enthusiasm.

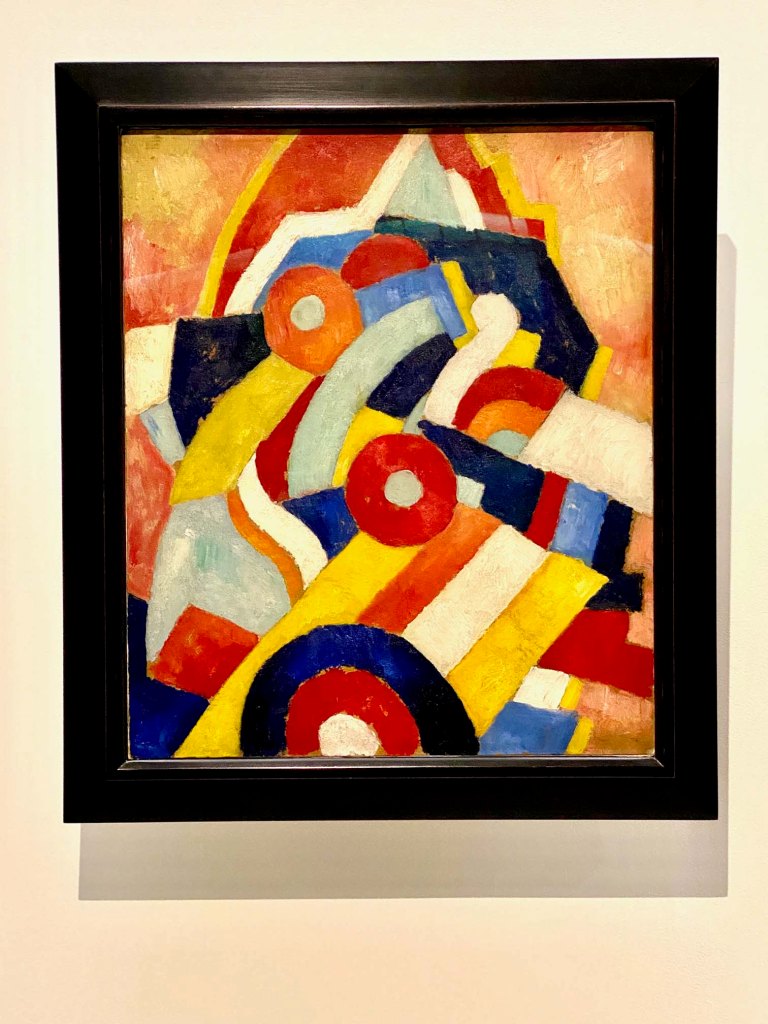

Avant-garde power couple Robert and Sonia Delaunay broke from analytic cubism’s monochromatic approach and injected pulsing color into the art-scene conversation in Paris.

Inspired by 19th century color theory (wheels demonstrating complimentary and dissonant colors), they painted swirling orbs pulsing with harmonies and contrasts to show optimism about the future.

Modern buildings like the Eiffel Tower, electrification of city streets, and the syncopation in dance-hall music created a pre-war energy in Paris that motivated these “orphists.” Everything seemed to be happening simultaneously. Harmonious and dissonant colors and whirling shapes on large canvases seemed a good way to represent it, as shown in the Guggenheim’s fun musical promo:

The style was named “orphism” by none other than Apollinaire himself. Robert Delaunay’s works in the exhibition include some of his early experimentation with abstract oval “windows,” his abstract riffs on the cosmos, and canvases still showing a hint of the real world. All convey the simultaneous push-pull of Paris, modern life, and larger scientific forces.

Many of Sonia’s orphist paintings are featured, including a gigantic horizontal color work inspired by the dynamic movement of tango dancers at a popular Parisian club. No doubt the massive 2024 Bard Graduate Center Gallery show about her forays into fashion and other creative fields (Sonia Delaunay: Living Art) influenced the Guggenheim curators to include her painted toy box and her celebrated super-tall accordion-book painting representing her collaboration with poet Blaise Cendrars.

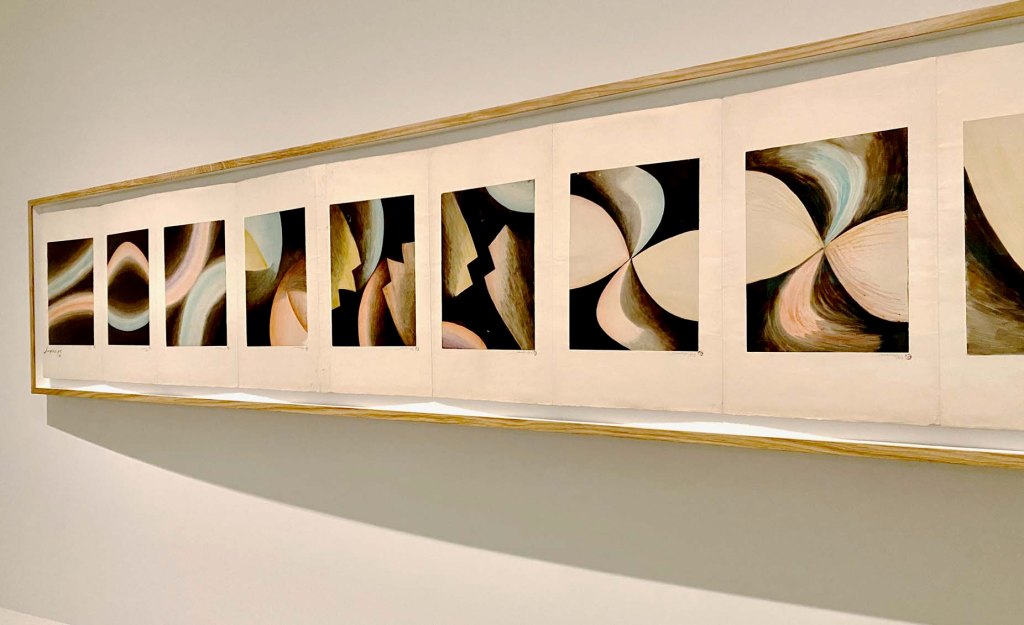

Innovations by the Delaunays are placed alongside other artists’ works that reflect the artistic breakthroughs of the early Twentieth Century – Kandinsky’s abstraction, the Blue Rider group’s symbolic use of color, and the synergies that artists felt between abstraction and music. In 1912, Leopold Survage intended to create the first fully abstract film, but the project was halted by World War I. Fortunately, we can envision his plan from his series of dynamic color drawings.

The music that inspired the Orphism is referenced throughout the exhibition – the improvisation and free structure of jazz, the dissonance of cutting-edge experimental music, and the staccato of the latest Parisian dance-hall craze – Argentine tango. The curators have even provided musical tracks to underscore this influence.

The Italian futurists Balla and Severini are also featured. Speed, modernity, and simultaneous city sensations were their bread and butter, too, even though they argued in the press and art journals that Futurism and Orphism were totally different.

In pre-war Paris, American modernist painters Marsden Hartley, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, and Morgan Russell picked up on Orphism, although the latter two rebranded their work Synchronism when they wrote their manifesto.

Even after the War, the Delaunays continued to represent orphism even if they occasionally incorporated real-world elements. Early orphism adopter Albert Gleizes also continued in this style throughout his career, and inspired students like Mairnie Jelett to explore color theory and its potential.

Take a look at our favorite works in our Flickr album here, and enjoy a syncpated strut through the colorful side of Modernism in this catalog preview: