When you enter the exhibition American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection, on view at Lincoln Square through January 3, you may experience a nostalgic feeling seeing images of early Americans, spectacularly pieced quilts, and finely carved wooden relics of bygone eras.

But the purpose in bringing all of these small masterpieces together is to present the in-depth stories behind the creators and subjects, which adds a completely different, lively layer to the journey through the three galleries – tales of itinerant portrait painters, stagecoaches along America’s first turnpikes, independent women surviving husbands and adventures in the Wild West, and back-country singing masters making their own teaching tools from roots and berries.

The stories make each work come alive, taking you back to the founding of America, looking at how people moved around in the Nation’s early years, made social-justice and political statements through their art, and used their artistic skills to transform their lives.

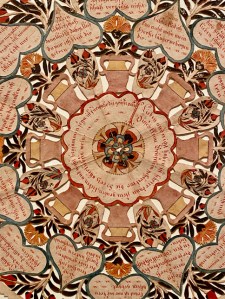

The first section of the show has several works with early German immigrants, many of whom came to America as Hessian mercenaries fighting for the British and stayed as citizens, using their artistic skills to pen intricate love letters and embellish important documents.

Portraits come alive as you see the fresh face of a 20-year-old mill worker (Eliza Gordon) who just arrived to take on her first independent job after leaving the family farm, portraits of new arrivals from the East Coast (the Bosworth siblings) who were starting new lives in up-and-coming Illinois, or a wife (Mrs. Bentley) committed to abolition who ran a famous spa in upstate New York in the early 1800s.

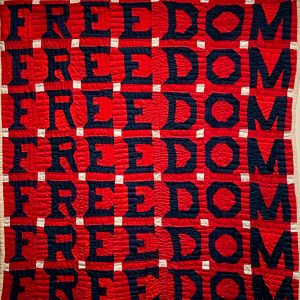

It’s not always easy to tell just from looking when works were made, and many come from the 20th century, often from a period later in the artist’s life – the drawing made by a Romanian immigrant (Ionel Talpazan) who used his art to work out his experience with a UFO as a child, the artist (Jessie B. Telfair) who made quilts in the Eighties to channel her feelings about being punished for registering to vote in Georgia in the Sixties, and a painter (Lorenzo Scott) whose portraits cast Atlanta beauties as Renaissance royalty whose style impressed him when he hung out at the Met in the years he lived in New York.

In the stories told about artworks involving far-away destinations, we learn that sea captain portraits were used as substitutes for husbands gone for years at a time, that many 18th-century students learned geography by copying intricate maps of exotic animal habitats, and that overhead rail was the magical mechanism that brought working-class people to the over-the-top fantasy destination of Coney Island.

The curators point out that the grand 1888 Grover Cleveland quilt was created by a woman who was a passionate political supporter. The quilt was her way of casting a vote for her favorite candidate, even though she did not yet have the right to vote. She even used the red-bandana campaign swag as the center!

Next to this, there’s a masterful “quilt” made out of wood by New Orleans artist Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, an Afro-Creole artist living in Treme.

Detail of 2014 wood “quilt” by Katrina survivor Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, Mother Sister May Have Sat in That Chair When She Lived in This House Before Me

The spectacular wall-sized work is pieced together from pieces of furniture that he salvaged from his home following his neighborhood’s devastation by Hurricane Katrina. Some of it pre-dated his residency, so the assemblage contains layers and layers of local history.

The final gallery contains works by people who used art to transform their lives – one of the thousands of abstract drawings made each night in West Virginia by Eugene Andolsek to relieve his workplace stress, and a large tiger with a personality carved and painted by Felipe Benito Archuleta, who was out of work in the Sixties and began carving animals to sell in Santa Fe.

His whimsical creations not only led to a wildly lucrative art career, but jump-started an entirely new direction for the New Mexico art market.

These tales are only a few of the 85 told by this exhibition. Download all the stories here, and enjoy some of our favorite works of art in our Flickr album.

Exhibition curator Stacy C. Hollander provides a virtual tour and shares some of her favorite stories about early-American artists and 19th-century travelers in this video below.

Stacy provides lots of background on Eliza Gordon and what her work was like in the textile industry. The video also tells the incredible story of Emma Rebecca Cummins (maker of the crazy-quilt trousseau robe), who was married four times, lived in five Eastern and frontier states (also Canada!), and worked as one of the first female Western Union telegraphers out West.

Enjoy getting to know the backstories of some of the incredible artists among the 85 featured in this tribute to American working artists, activists, and visionaries: