Take a look at generations of 20th century craft mentorship in Craft Front & Center: Conversation Pieces, on view at MAD Museum through April 20, 2025. The exhibition shines a light on how innovators shaped subsequent generations of craft artists at schools and art colonies across the United States. The curators have pulled from the MAD collection to show us the work of student and teacher side by side in several disciplines – fiber arts, ceramics, and glass.

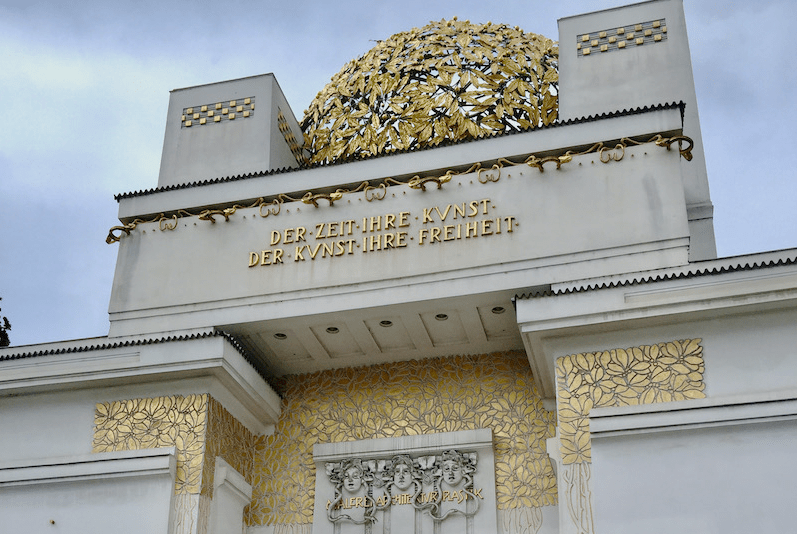

Many of the mentors either taught at or were influenced by the Bauhaus, the legendary early 20th century design incubator.

Bauhaus students could take classes in weaving, ceramics, typography, and metalwork alongside traditional fine arts classes. They were expected to excel in their applied-arts training and mix in aesthetics learned in their fine arts classes.

When the Nazis closed the progressive school in 1933, many German-Jewish refugee teachers and students fled, transplanting Bauhaus design and educational philosophies across the world.

MAD highlights several artists – including Anni Albers, Trude Guermonprez, Margeurite Friedlander Wildenhain, and Maija Grotell – who came to the United States and integrated Bauhaus practice into curriculums at Black Mountain College, the California College of Arts and Crafts, Cranbrook, and new craft workshops they began.

One of the best-known 20th century textile artists, Anni Albers is featured in the show by a fine-art “pictoral textile” made on a small handloom. At the Bauhaus, Albers she trained under master weaver Gunta Stölzl, and eventally took over as head of the textile workshop. Albers moved to Black Mountain College in North Carolina with her husband, painter Josef Albers, and was the first textile artist invited by MoMA to have a one-person exhibition.

Anni also designed commercial textiles for Knoll for years. Her influence on the next generation of painters and textile artists was profound.

MAD features work by two fiber-arts innovators (and Albers admirers) who pushed boundaries by crafting commanding, large-scale sculptures. Sheila Hicks (who studied with Josef at Yale) and Claire Zeisel (who studied with the former Bauhaus faculty at Chicago’s IIT) are credited as the leaders of America’s textile arts movement. Tufts burst from the wall in Hicks’ piece, and Zeisel’s hovers in the center of the gallery like a shaman.

Trude Guermonprez, an unconventional materials artist known for innovations in three-dimensional weaving once worked at Berlin’s textile engineering academy; later, she consulted with industrial textile firms, as did Anni Albers.

Next to Guermonprez’s dynamic 3D hanging woven sculpture, MAD shows us a piece by Kay Sakimachi, a student who met Guermonprez in 1951 at the California College of Arts and Crafts summer craft workshop.

Guermonprez encouraged students to use latest technology, and here we see how Kay used a 1959 invention by DuPont – monofilament that’s better known today as fishing line. Kay’s woven it into an ethereal hanging sculpture.

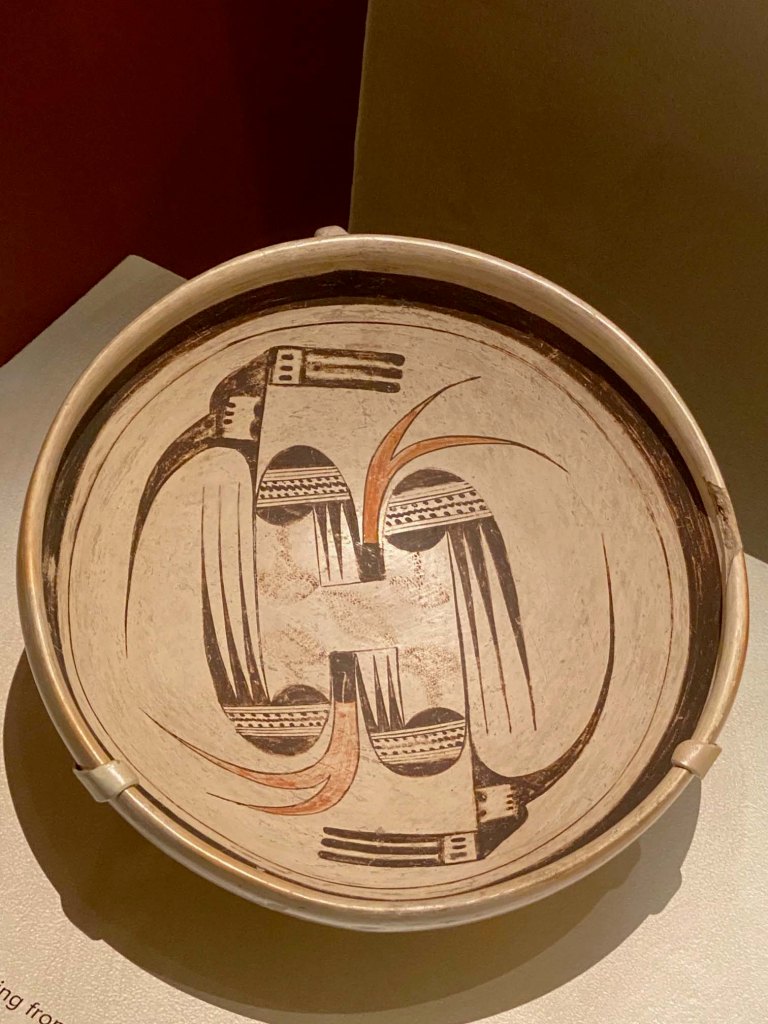

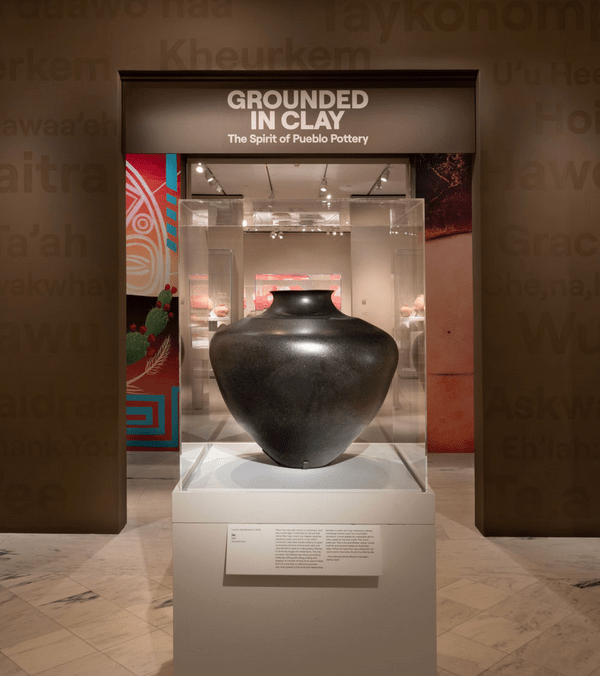

In ceramics, MAD displays a series of vessels that transform into sculptures, starting with a modest, contained piece by Margeurite Friedlander Wildenhain, one of the first Bauhaus students and the first woman in Germany to be honored as a master potter. After emigrating to the United States in 1940, Wildenhain founded Pond Farm Workshops in Sonoma County, California ad instituted a rigorous Bauhaus instructional approach.

Frances Senska, her ceramics student, applied Wildenhain’s instructional principles to her own classes at Montana State, where student Peter Voulkos learned how to breathe new life into clay. Voulkos shashed, prodded, and poked clay, vigorously transforming the humble medium into wild, dramatic expressions.

In turn, his UC-Berkeley student, Mary Ann Unger injected whimsey and improvisation into her sculptures, which allowed her daughter, Eve Biddle, to push it even further. MAD shows Biddle’s ingenious installation of creative ceramic geodes, trilobites, and spines crawling around the gallery wall.

Ceramics mentors even play a role in the development of America’s Studio Glass movement, which begins with Harvey Littleton, whose dad was a physicist on the first reasarch team at Corning Glass Works (he later developed Pyrex). MAD displays Harvey’s gorgeous glass arcs.

On weekends, Harvey spent lots of time with his dad in the Corning lab, assuming he would follow in dad’s footsteps as a physicist at the University of Michigan. But after Harvey experienced UM art classes, he switched major. Eventually, he was specializing in ceramics under Maija Grotell at Cranbrook Academy of Art (who also taught ceramic superstar Toshiko Takaezu).

Littleton’s travels to observe the Italian glassmaking masters at Verano inspired him to apply his kiln and physics skills to experimental glassmaking. Back home, e pioneered low-temperature glass-blowing techniques that enabled glass artists to create work in studio setting and not a factory.

Littleton achievement was established the first university-based glass-blowing program at University of Wisconsin-Madison. A lucky undergraduate, Dale Chihuly, learned from the master, and the rest was history for American glass making.

After receiving his MFA in ceramics at RISD, Chihuly traveled to Venice (like his mentor), and observed how the team worked together to create a finished work of glass art. In 1971, he founded Pilchuk Glass Works in Washington State, where he emphasized the collaborative, collective process. Chihuly’s own sculptural wonders emerged, plus the next generation of indigenous glass artist gained experience in collaborative expression – Tony Jojolla and Preston Singletary.

There are many more stories told in this illuminating exhibition from the MAD collection. Take a look in our Flickr album.