A big, red blob on the fifth floor at MoMA is the welcome sign to one of the most engaging exhibitions in New York – the come-hither array of modern artworks in the latest Artist’s Choice show, Amy Sillman: The Shape of Shape, on display through October 4.

But here’s the catch for MoMA visitors – the show has more than 75 works but no labels, no identification, no dates. Just the clue that Amy chose works to explore the role of “shape” in modern art. Small artworks are arranged knee-level on risers (kind of like stadium seating), with larger paintings tilted against the wall. A few are hung in the traditional way, but it feels as if MoMa’s collection is looking at you and hankering for a conversation. Check it out in our Flickr album.

Rectilinear frame conversation between 1989 Albert Oehlen painting and 1935 “Construction” by Gertrude Green

In our first visit back to the re-opened MoMA, visitors circulated through the room, looking intensively, talking about what they saw, and discussing how pieces might be connected. Although the gallery guide was available via QR code, no one during our visit appeared to seek it out. Everyone seemed quite content to parachute into 110 years of modern visuals and just go for the ride.

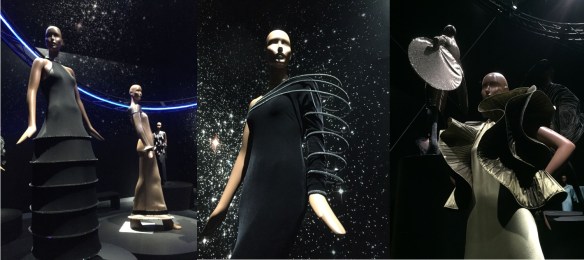

What did Amy choose? Abstracted forms, organic shapes, human bodies, and not-bodies – all arranged in a way that makes you feel that one is somehow related to its neighbor. You can’t quite describe why the entire room felt like a tight ensemble, even though one piece might feel like fun and the next a little scary.

It was interesting how unsettled visitors felt by 1970s works by Christina Ramburg and Julian Schnabel. This is exactly what Amy was going for, according to what we overheard her tell students in the gallery yesterday. She wanted to evoke the anxious feelings that most artists experience as they paint, draw, and sculpt and to reflect the times today without being didactic.

Along the east wall – 2008 acrylic by Charline von Heyl, 1920 Arp sculpture, and 1976 drawing by Jay DeFeo

Shadowy Black figures in a dark painting by Zimbabwean artist Thomas Mukarobgwa are echoed by a shadowy figure in a work by Leger. The tiny 1920 stacked Arp sculpture seems to be playing a “Mini-Me” role next to the large, layered 2008 Charline von Heyl acrylic.

Shadows also play key roles in a Lois Lane painting paired with a Kirschner wooduct. See for yourself and make a connection. Download Amy’s zine here to learn more about the works she chose and how she installed them. (She designed it during the quarantine months when the show was shut down.)

Here’s a short overview of the show hosted by MoMA painting/sculpture curator Michelle Kuo:

But you should really dig into the in-depth conversation (with over 10,000 views!) between Amy and Michelle, if you’ve ever been to art school or painted. They talk about art making, art history, Amy’s inspiration from Munch’s little-known litho of a woman hugging a bear, and the way she chose lesser-known works that could have a conversation with you in 2020:

More on MoMA’s reopening

MoMA on 53rd Street is open every day with timed ticketing, and now that the free-ticket offer has concluded, it seems easy to find a time to visit. The Queens outpost at P.S.1 is open until 8:00pm Thursday through Sunday, and is currently showing the acclaimed (and long-anticipated exhibition) Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration through April 4.