After more than 55 years, the camel herd is back at the Whitney. When they first appeared in 1969, the dromedaries were a media sensation. Who could resist the delight of seeing the life-sized camel sculptures by 28-year-old science nerd Nancy Graves nonchalantly going about their business in the pristine, white Breuer building?

At the new Whitney, the camels are welcoming everyone to Sixties Surreal – a superb exhibition (on view through January 19, 2026) that pulls out an array of engaging, cheeky work from that tumultuous decade. The show presents work by over 100 artists who chose to remain on the fringes of the big-time art world, creating pieces that poke at the Establishment, consumer culture, and social norms.

The Whitney makes the case that American artists of the Sixties were not echoing the themes of European Surrealism (dreams, subconscious desires); but they did adapt a few of that group’s visual techniques to reflect and critique what was happening in America in off-center, slightly surreal ways.

The Sixties was a decade when cultures were clashing, TVs were showering a kaleidoscope of images into people’s living rooms, nuclear catastrophes loomed, and people were landing on the Moon.

The exhibition shows how artists who didn’t belong to trendy “isms” still managed to create work that has stood the test of time – the Hairy Who of Chicago, the funk-and-pun artists of California, the downtown post-minimalists of New York, emerging Native American modernists, and social-justice artist-advocates.

Take a look at some of our favorites in our Flickr album.

At a time when hard-edged minimalism and Pop Art ruled, the curators want us to see and experience (again) artists whose work was featured key exhibition showcases like Lucy Lippard’s 1966 Eccentric Abstration show at Fischbach Gallery in New York and Peter Selz’s 1967 Funk show at the Berkeley Art Museum. Each were full of work that defied contemporary art-world conventions.

The Whitney’s chosen to showcase several pieces of one of the artistic godfathers of the funk movement – H.C. Westerman. His satiric “minimalistic” shag carpet sculpture sits next to a William T. Wiley painting, but it’s wonderful to contemplate two virtuoso carved pieces – The Big Change and Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea.

The first gallery presents disquieting creations that present strange, out-of-context juxtapositions, weird images, and out-of-proportion everyday objects that seem to reflect the feeling that we’re living in an off-kilter world. A large Rosenquist hovers over the gallery, but its muted tones and dissonant images evoke a far different mood than his famous, epic, over-the-top F-111.

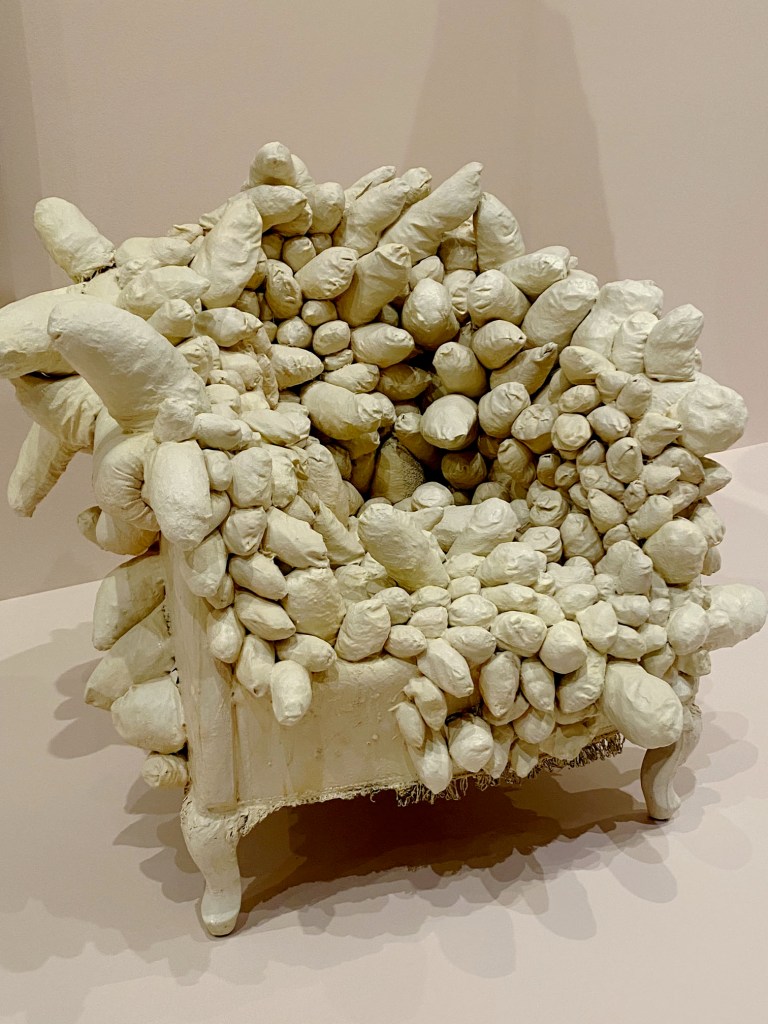

Another section presents work – many from repurposed or recycled material – with sensuous forms that suggest – but not directly depict – the human body. It’s nice to see such an array of soft, draped, and biomorphic work by artists like Kusama, Eva Hesse, Kay Segimachi, and nearly forgotten Miyoko Ito.

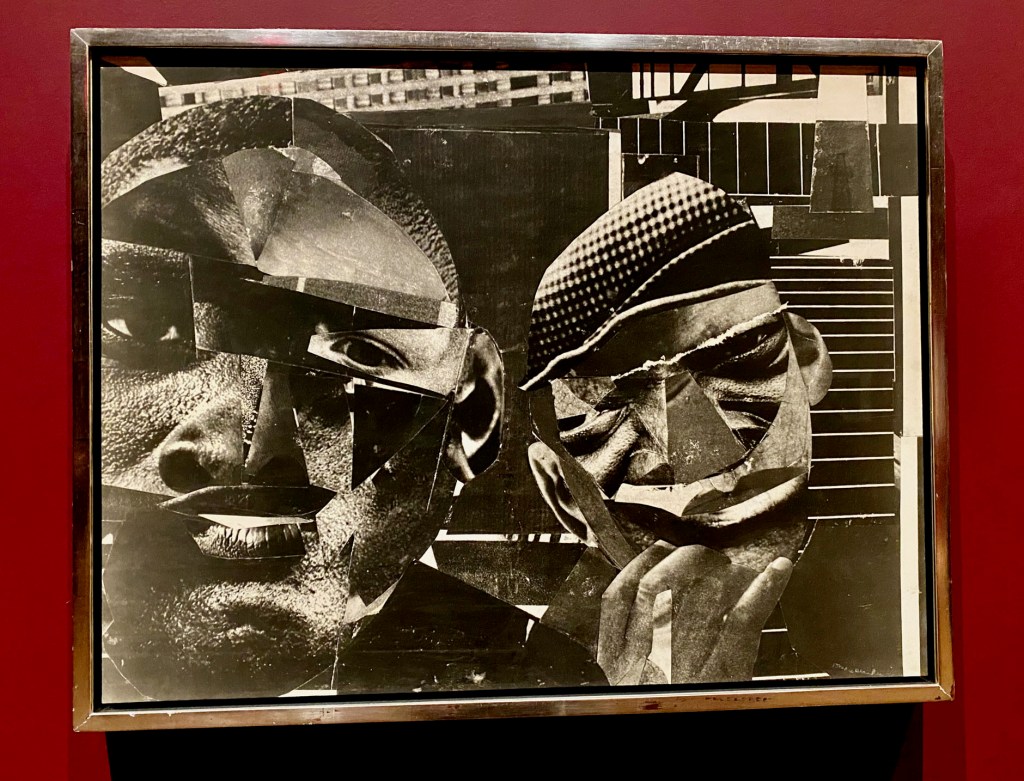

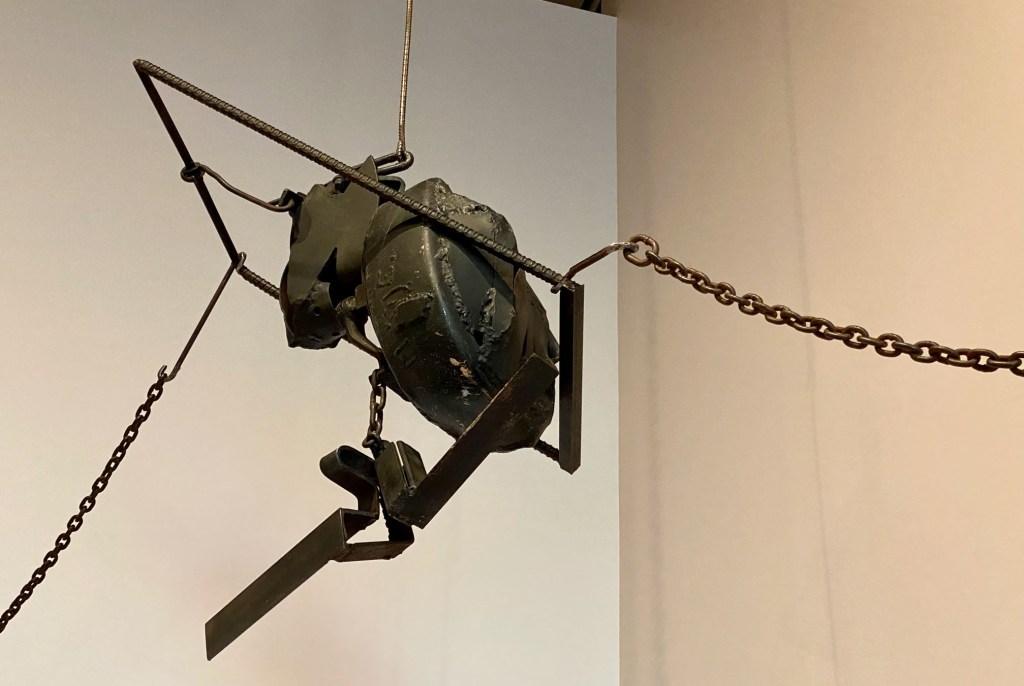

The far end of the exhibition presents works that take a stand to push for change in the world. Jasper Johns and Fritz Scholder let their paint do the talking. But others use a dada tactic to get the point across – hard-edge collages and assemblages.

Works by Romare Beardon, John Outterbridge, Ralph Arnold, and Melvin Edwards create surreal dissonance that still packs a punch decades later.

The show concludes with a selection of works by artists reflecting alternative spiritual practices and beliefs. At a time when organized institutions and religions were being questioned, why not turn inward?

Have fun strolling through the Whitney’s Sixties Surreal galleries to a totally throwback Sixties soundtrack:

To hear more about specific works, listen to the curators talk about individual works in the audio guide here.