An exhibition of dramatic, action-filled prints by legendary Abstract Expressionists shows how experts at the new printmaking workshops during the Sixties and Seventies gave art-world mavericks the tools to take their ideas to new dimensions.

Push & Pull: The Prints of Helen Frankenthaler and Her Contemporaries – on view at the University of New Mexico Art Museum through May 17, 2025, is a must-see journey into collaboration and experimentation at mid-century.

UNM recently received a gift of 20 magnificent artworks from the Helen Frankenthaler Print Initiative.

The main gallery shows them alongside prints by Elaine de Kooning, telling the story of how these remarkable abstractionists collaborated with different workshops, used their distinctive styles to create portfolios, and formed decades-long bonds with master printers.

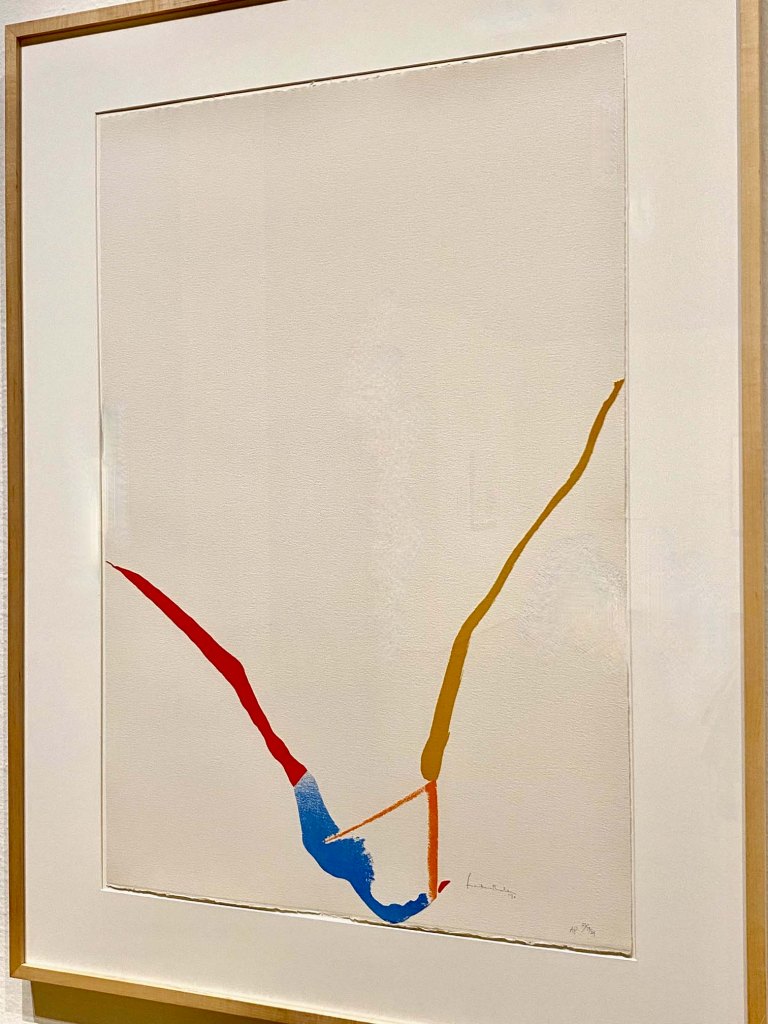

Helen Frankenthaler grew up and studied in the ever-evolving New York City art world. Her studies with Hans Hoffman – known for teaching abstractionists how to capitalize upon the “push pull” of color – and her technique of physically soaking and staining colors across canvases laid on her studio floor put her squarely at the intersection of the Abstract Expressionist and Color Field painting movements.

Frankenthaler had her first big solo painting exhibition in 1960, and began her printmaking experiments the following year. Some of her earliest works in the exhibition are silkscreens – some in the color-field direction, and some more gestural.

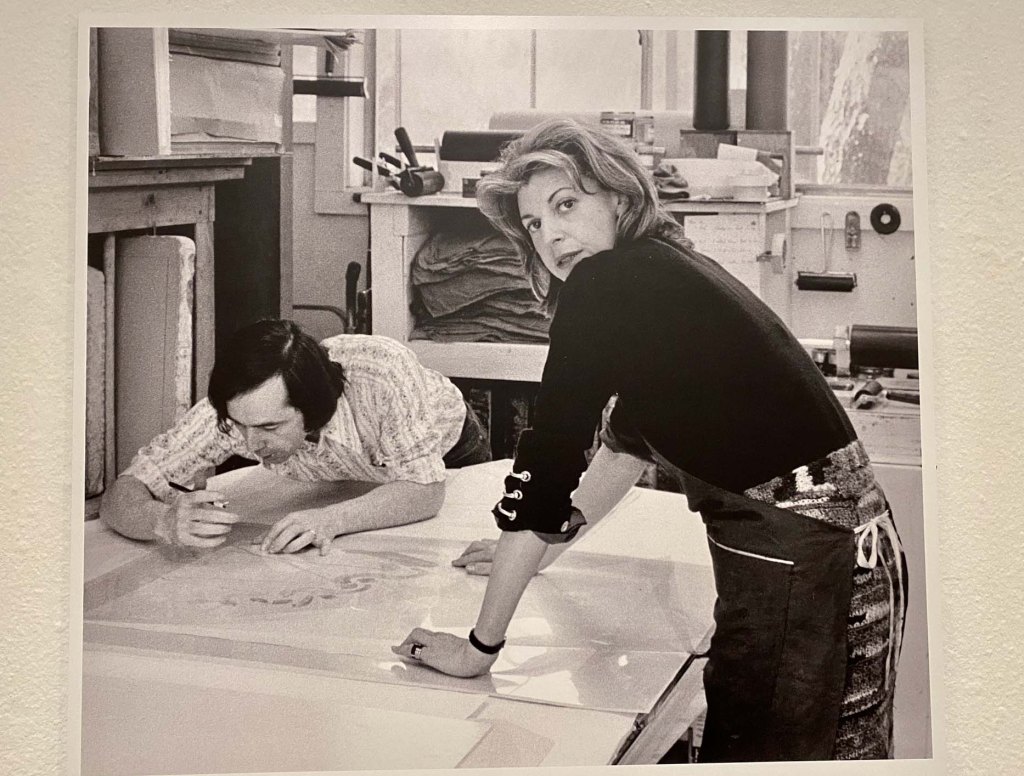

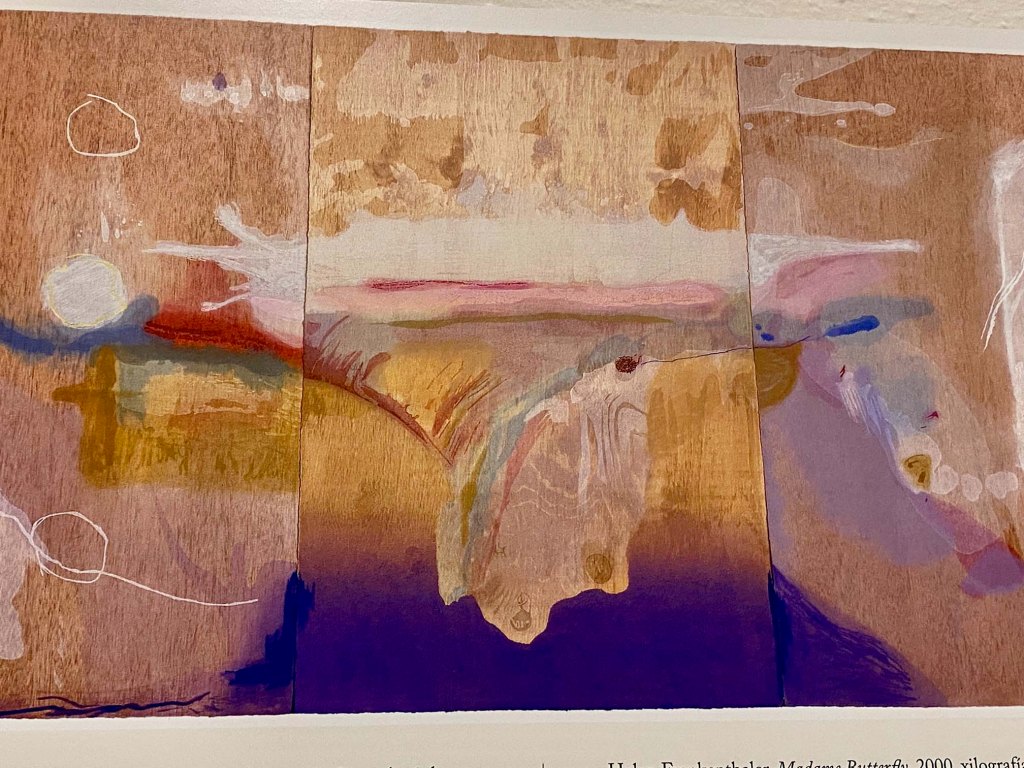

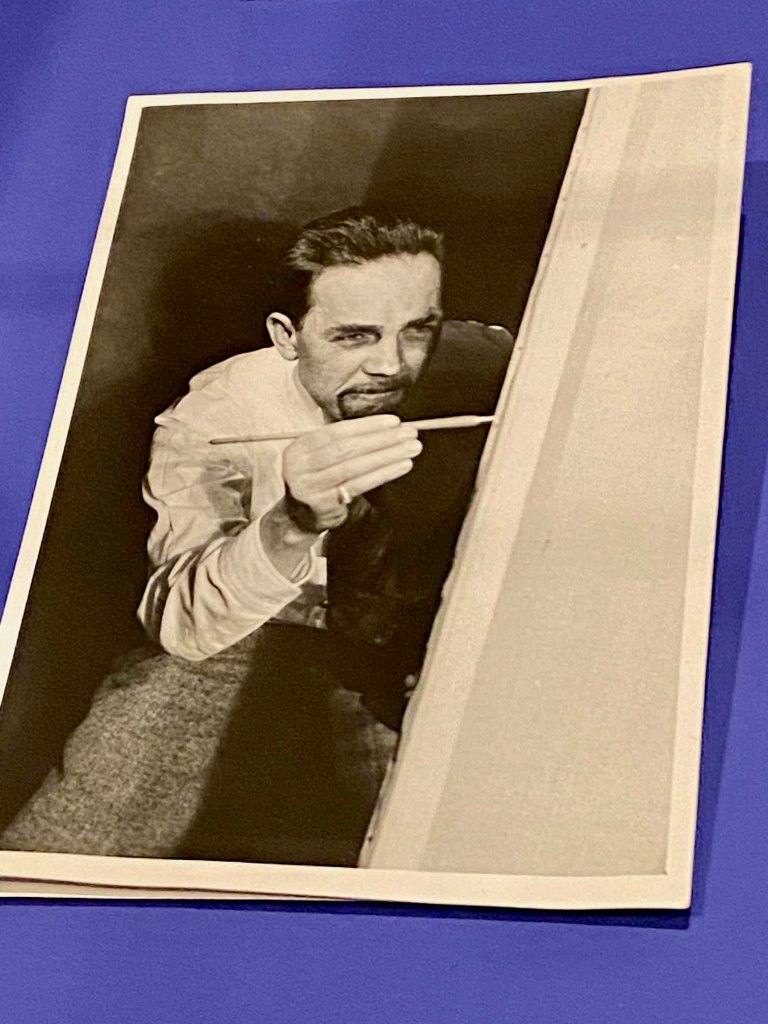

Frankenthaler’s prints are grouped according to her work with various presses, such as Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), Tyler Graphics Ltd., and Tamarind Institute. Often with the guidance of print masters, she experimented to see how her “soak stain” could be layered and pressed multiple times across the lithography stone.

The exhibition curators display a series of proofs and experiments at Tyler Graphics to demonstrate the artist’s creative process with the expert printmaking team.

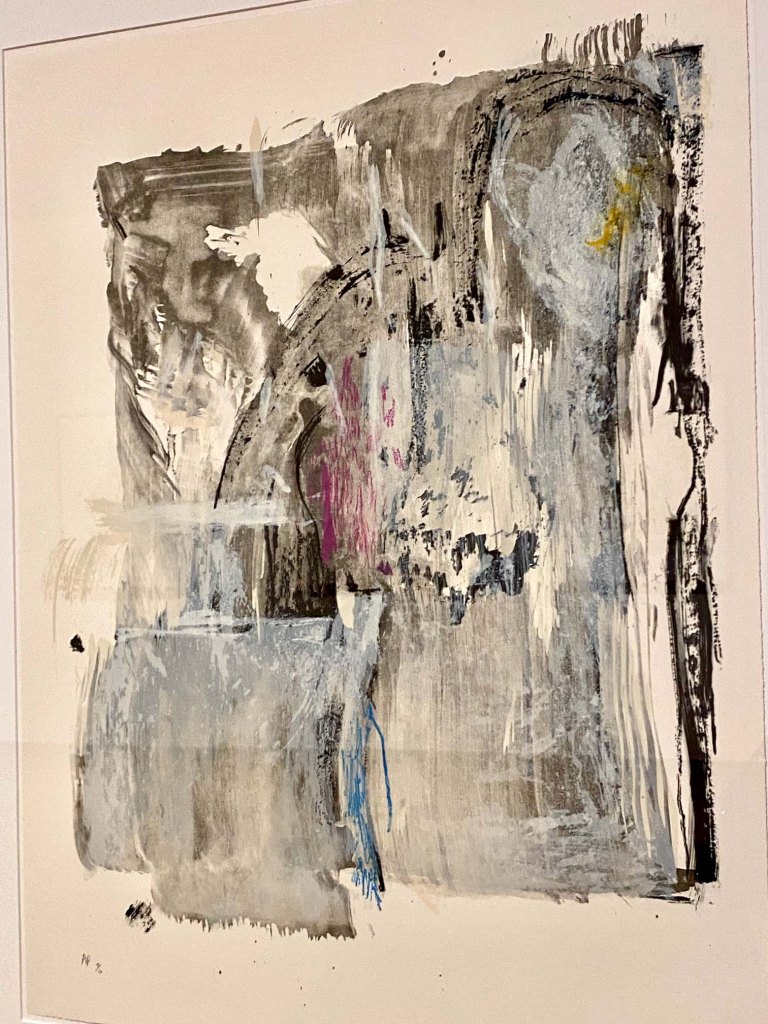

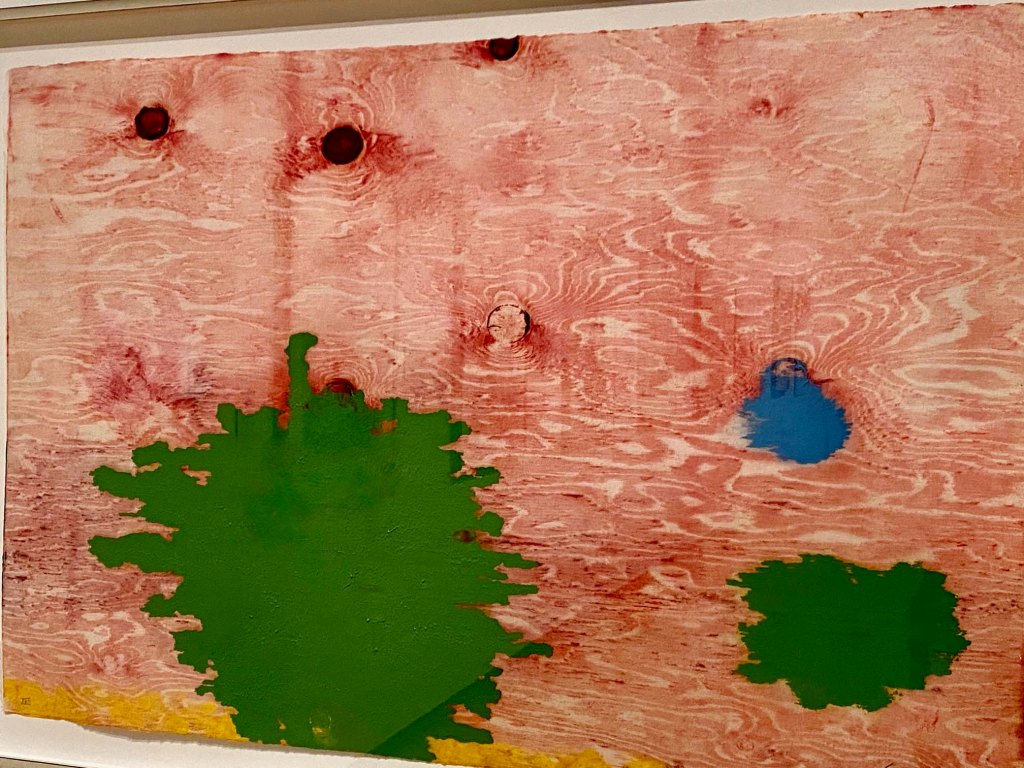

Later experiments show off Frankenthaler’s experimentation with woodcuts and monoprints. Here, she inked a woodblock and ran it multiple times to produce a “ghost print” of the wood, then applied bright red over the wood knots and added bright blobs of floating colors atop the natural backdrop.

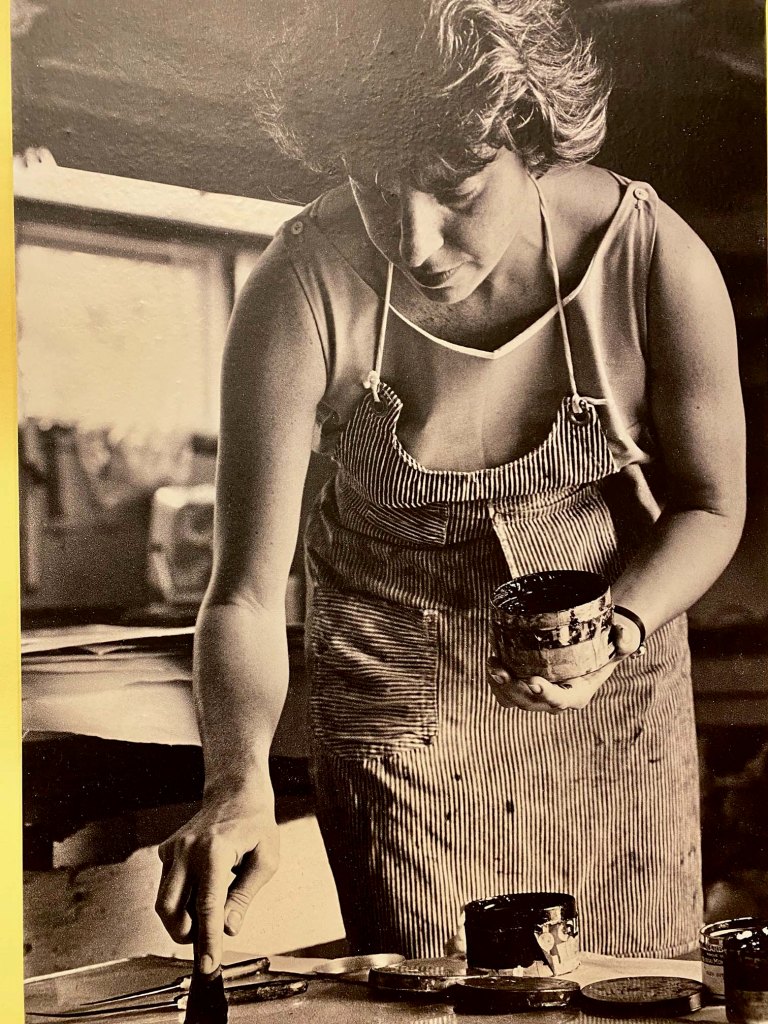

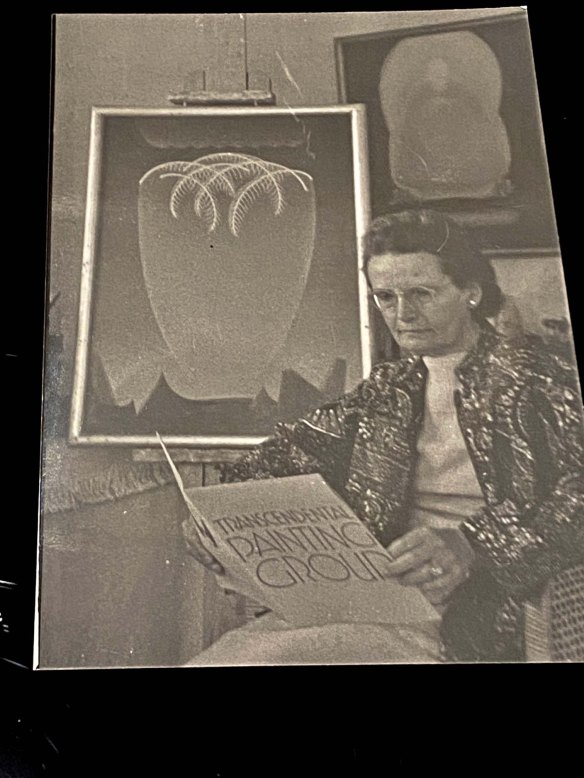

The exhibition also showcases two dramatic print series by action painter Elaine de Kooning made at the Tamarind Institute. Check out Elaine’s wild lithographs of bulls.

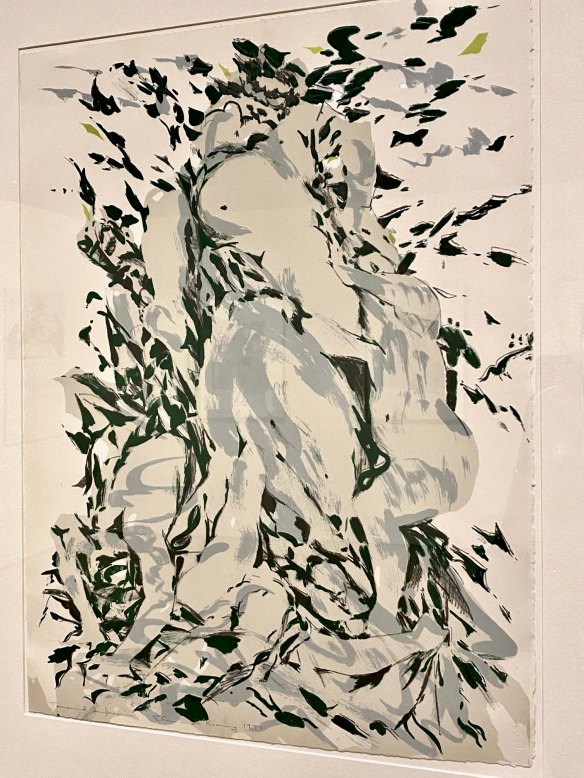

The curators also showcase Elaine’s multiverse interpretation of a famous Parisian sculpture in the Jardin de Luxembourg. The series mounted across the long wall gives gallery goers a close-up look at the intricate collaboration between Tamarind’s workshop masters and a midcentury mark maker.

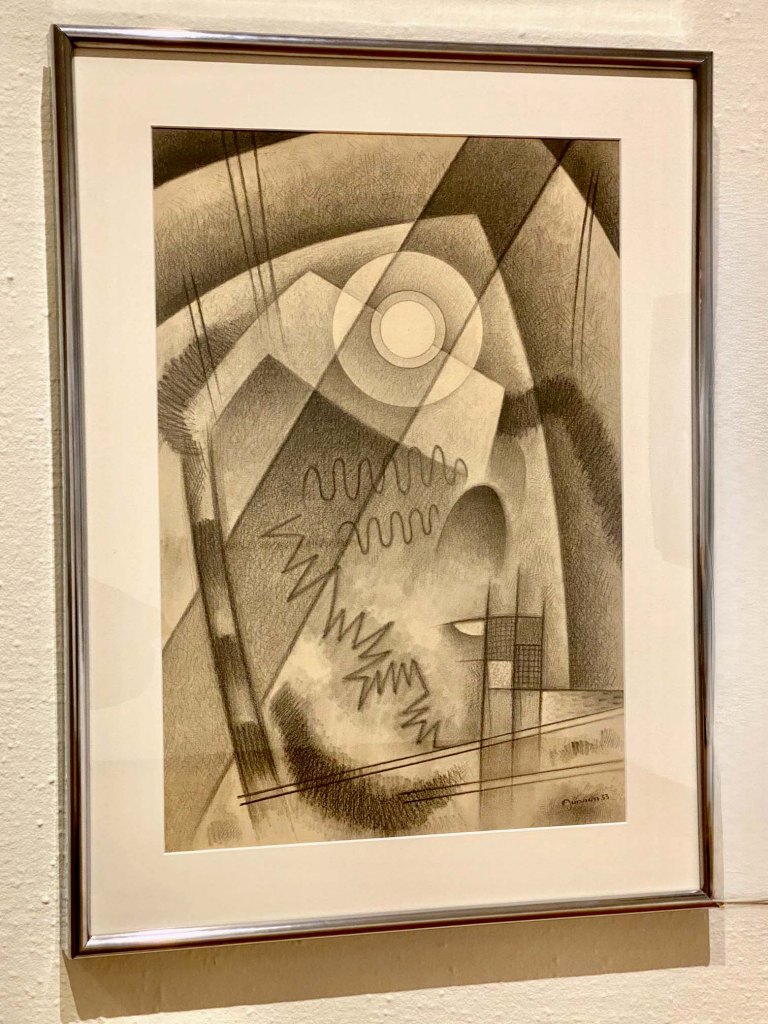

The exhibition also includes prints from plenty of other mid-century abstractionists from the UNM collection – Motherwell, Diebenkorn, and Lewitt – as well as prints by current UNM students who were asked to create art inspired by Frankenthaler and company.

Take a look at all of these action-packed prints in our Flickr album.