To see the works by one of the top virtuoso portraitists of the 20th century, drop into the home that Nicolai Fechin designed and built for his family in Taos, New Mexico. Masterful oil and charcoal portraits created throughout his life are hung in quiet, contemplative corners of his spectacular 1920s home as part of Masterful Expression: Nicolai Fechin’s Portraiture, on view at the Taos Art Museum at Fechin House through December 31, 2025.

The house itself is a masterwork with all the doors, railings, and embellishments carved by Fechin’s own hand, but the portraits and small, carved wooden busts show why he is considered one of the greatest Russian artists ever to take up residency in the United States.

Fechin grew up during the time when Russia was ruled by the Czar, and thrived at the Higher Art School of the Russian Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, where he studied with the acclaimed Russian history painter, Ilya Rapin.

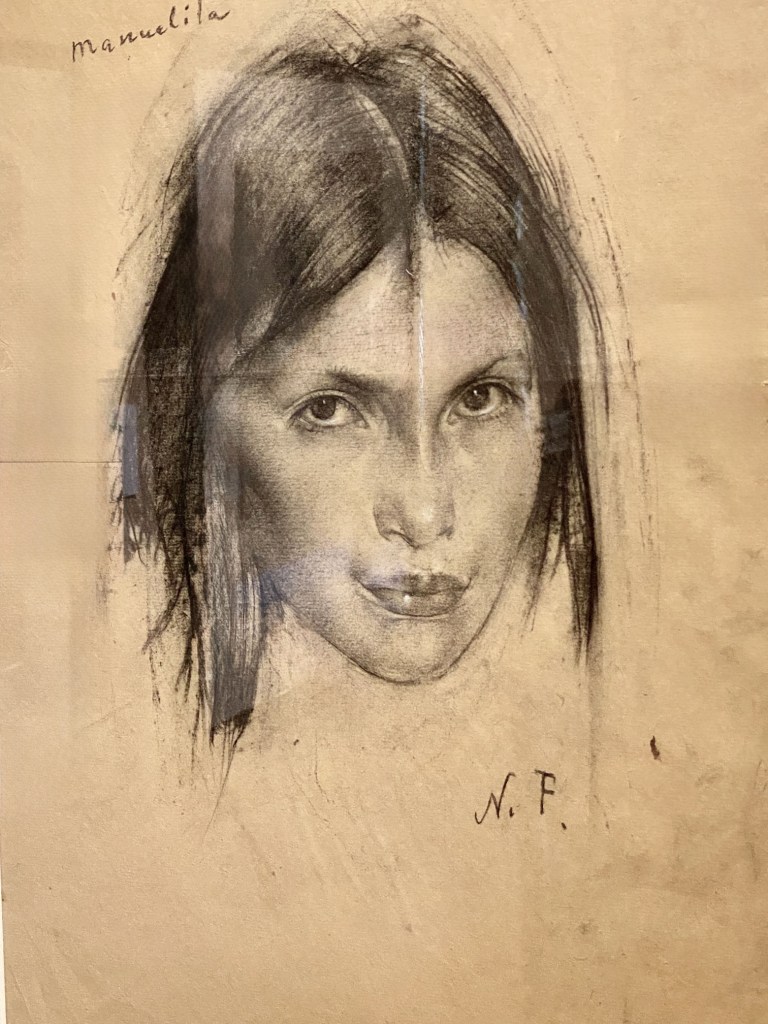

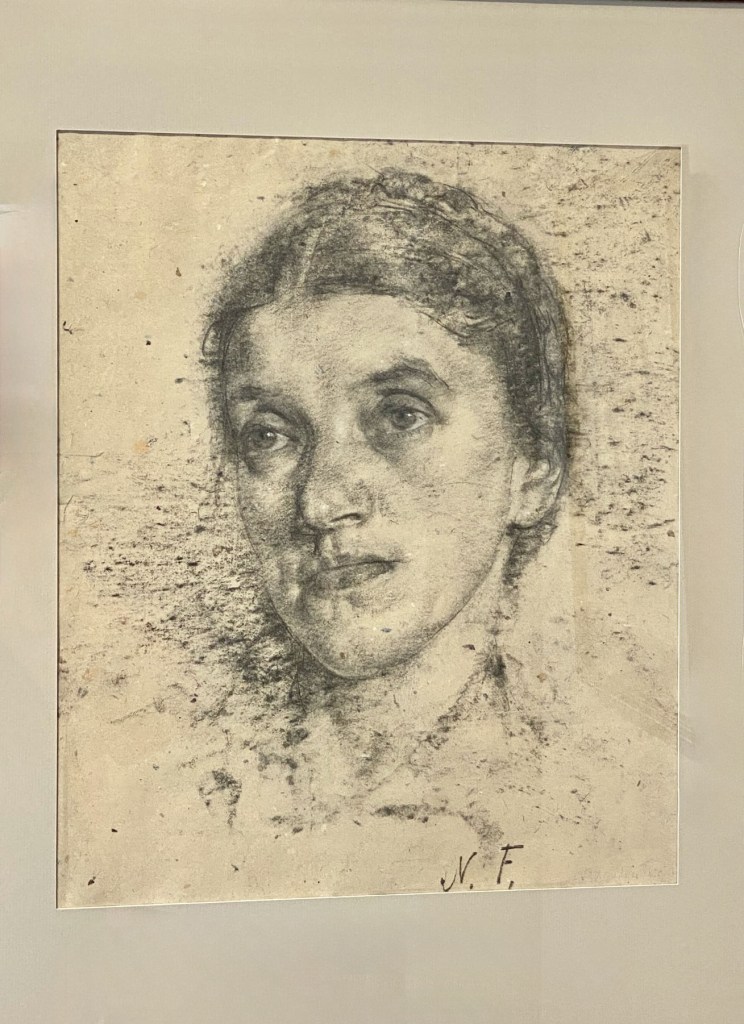

Fechin’s classical training followed the principles advocated by the French virtuoso, Dominque Ingre – subtle human expression, anatomical awareness, and verisimilitude that jumps right of the page (or canvas).

Fechin learned his lessons well and won national acclaim in Russia by 1908 for his grand, epic depictions of peasant life, which provided an opportunity for his work to be shown internationally and gain fans in the United States. But it was his reputation for portraits that captured the essence of human expression that cemented his reputation in the United States and provided him with continuing commissions.

When the Russian Revolution and civil war brought disruption to the domestic life he was starting to build with his new bride, Alexandra, an American benefactor arranged for them to emigrate to the United States. As soon as the Fechin family landed in the United States, the commissions began, largely due to the enthusiastic public reaction his portraits in shows at the Grand Central Gallery and the Brooklyn Museum.

For health reasons, Fechin and his family left the sophisticated steets of New York City during the high-flying 1920s for the high desert of Taos – a thriving art community anchored by Mabel Dodge Luhan. Fechin figured that when the tumult in Russia died down, he would return. But that never happened.

The exhibition, with many works drawn from private collections, provides a glimpse of the Fechin family over time, with portraits and sculptures of his wife early in their courtship (an oil), a bronze bust, and drawn portraits in their life in New Mexico.

His beloved daughter Enya – who ultimately saved and restored this unforgettable home and her dad’s studio – is shown as a baby in Russia, as an older child in carved wooden busts, and in paintings in her coming of age, as well as a portrait of her as a grown woman looking out for her dad later in his life.

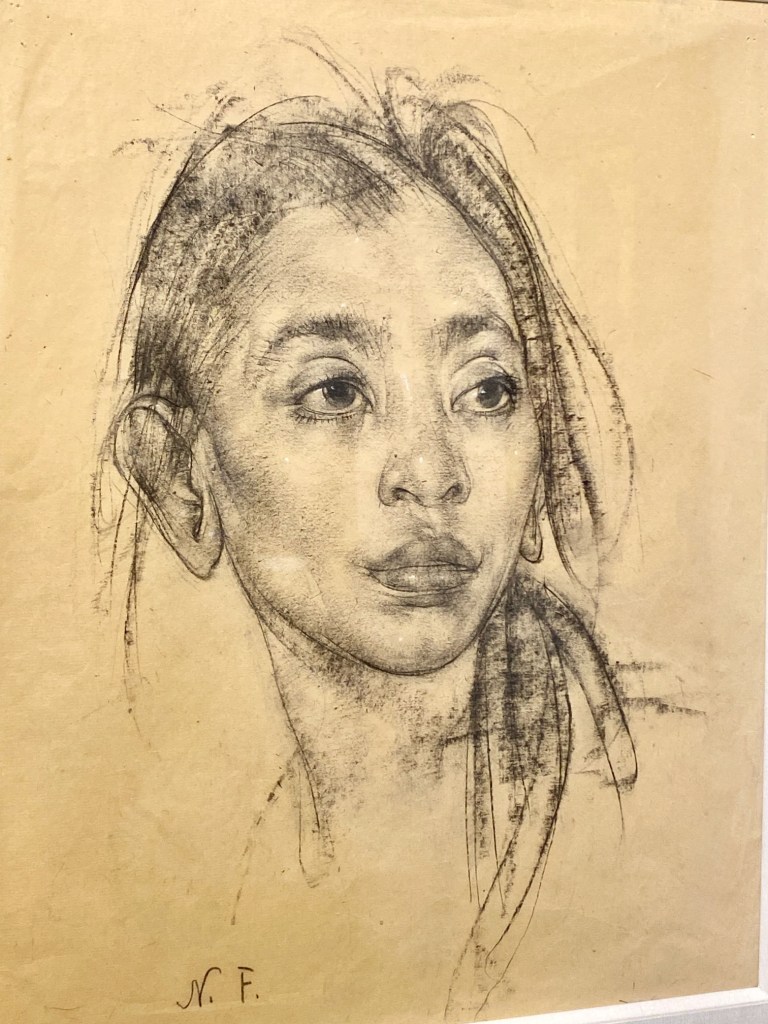

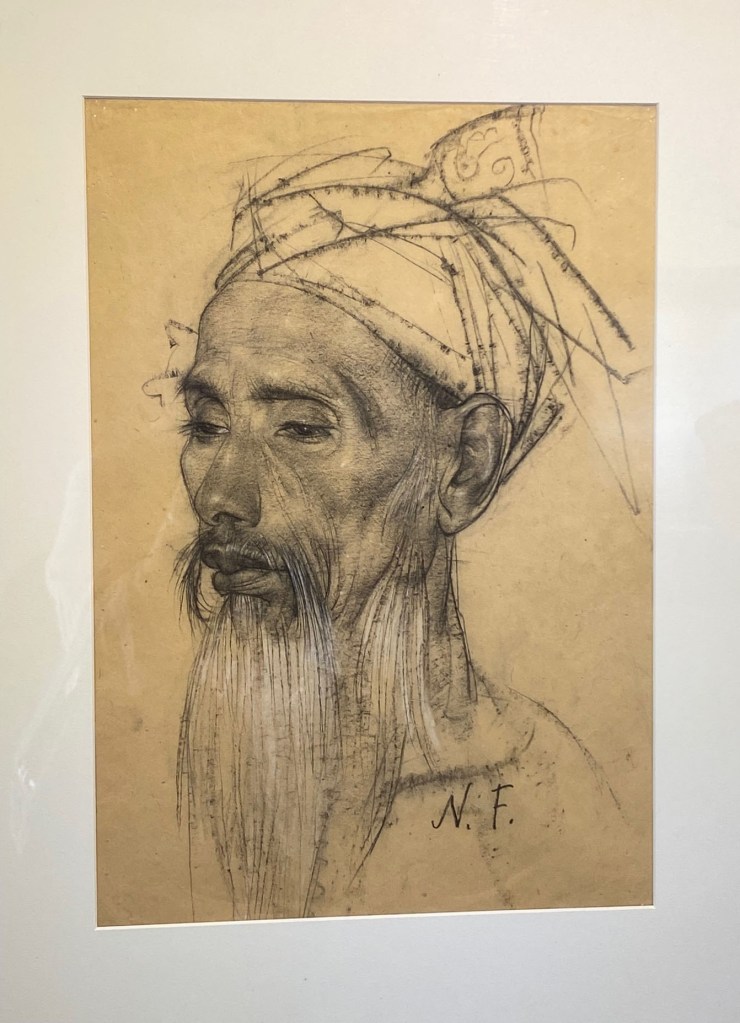

The exhibit also includes sensitive, gorgeous portraits and studies that Fechin created in his five-month stay in Bali in 1938 – delicate features of young models and reflective expressions of respected elders. All have clean, sure lines and carefully observed, personalized nuances.

This walk-through the Fechin home holds delight and awe at every turn – awe at the hand-carved interiors and delight at at the humanity and diversity of the faces greeting us in every room. Visit, if you can!

Take a look at more in our Flickr album.