How does it feel to have the eyes of 200 years of art history upon you, peering out from portraits, history paintings, and scenes of everyday people? What stories do they have to tell you? And who gets to tell the history and make the story?

Find out by contemplating works by over 100 artists nurtured and celebrated by PAFA in Making American Artists: Stories from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1777-1976, currently on view at the Albuquerque Museum through August 11, 2024…but coming soon to a museum near you (see below)!

While renovations are happening at the Academy in Philadelphia, the curators have chosen some of PAFA’s most iconic works to be shipped cross-country and installed “in conversation” with works by PAFA artists who may not be household names but were nonetheless ahead of their time.

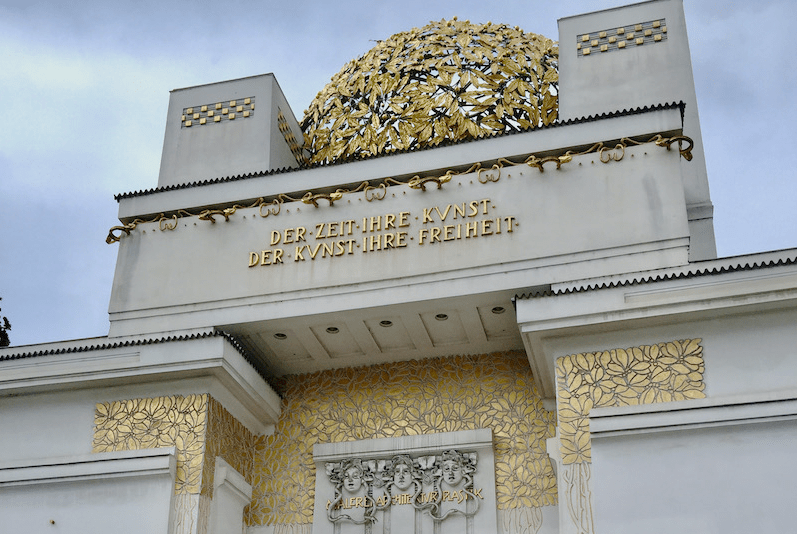

It’s all a tribute to legacies preserved in the oldest art museum + art school in the United States, founded in 1805 by the dynamic duo of William Rush and Charles Willson Peale, both Continental Army militia (and artists!) during the American Revolution.

Mr. Rush carved the bow figures on most of the ships for America’s first Naval fleet. All of those ships are now long gone, so it’s nice to see that we can admire his majestic Eagle in this exhibit.

Mr. Peale, one of the Sons of Liberty who served under and painted General Washington, later founded America’s first natural history museum on the second floor of Independence Hall. He also passed his talent on to the next generation through his very large family of artistic prodigies.

These two artists of the Revolution walked the walk and talked the talk and passionately felt the young nation needed an art academy.

PAFA’s first hundred years had some ground-breaking firsts – the first exhibition that included both male and female artists (1811), admission for Black artists (1857), and first female instructor (1878).

The show kicks off with a masterful history painting by Benjamin West, a Pennsylvania painting genius who landed in England in 1763, helped to found the Royal Academy, and somehow remained best friends with both King George III and Benjamin Franklin at the same time. He revolutionized history painting by depicting contemporary subjects and taught (in London) a who’s who of Americans artists – Peale, Stuart, Sully, Morse (who invented the telegraph and code), and Fulton (who invented steamships).

In addition to masterworks by West and Gilbert Stuart, the exhibition showcases many works by female and African-African artists associated with PAFA – Patience Wright (America’s first professional sculptor), Cecilia Beaux (first female teacher), Henry O. Tanner (first successful African-American painter), and superstar Mary Cassatt.

In the day, grand history paintings were primarily the work of men, but the exhibition emphasizes that many enterprising 19th century women still found ways to make it in the art world. They specialized in “lesser genres,” like portraits, still lifes, and scenes of everyday life. Check out our favorites in our Flickr album.

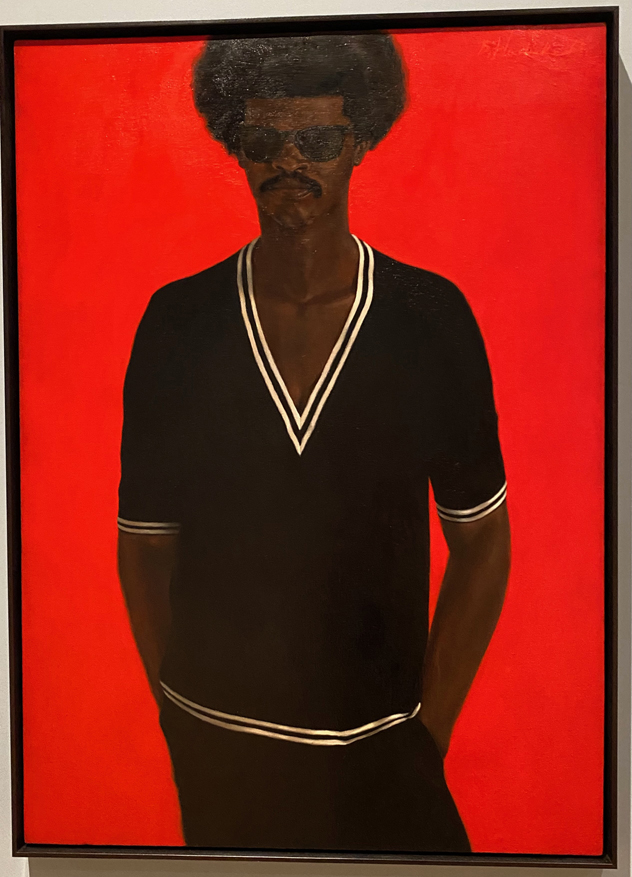

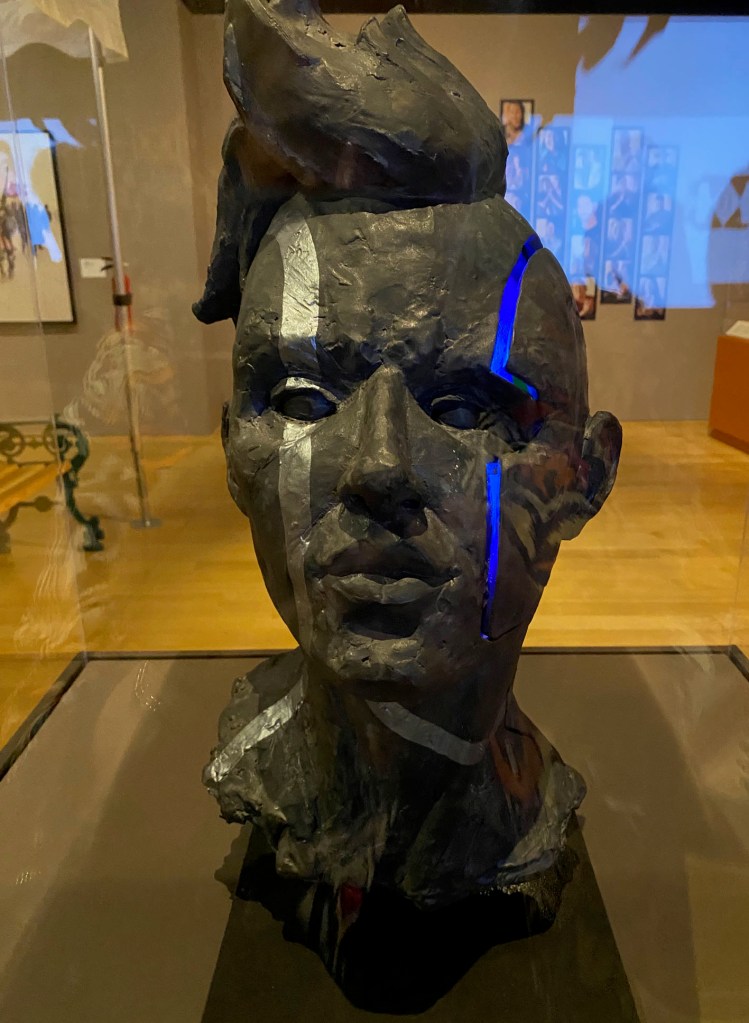

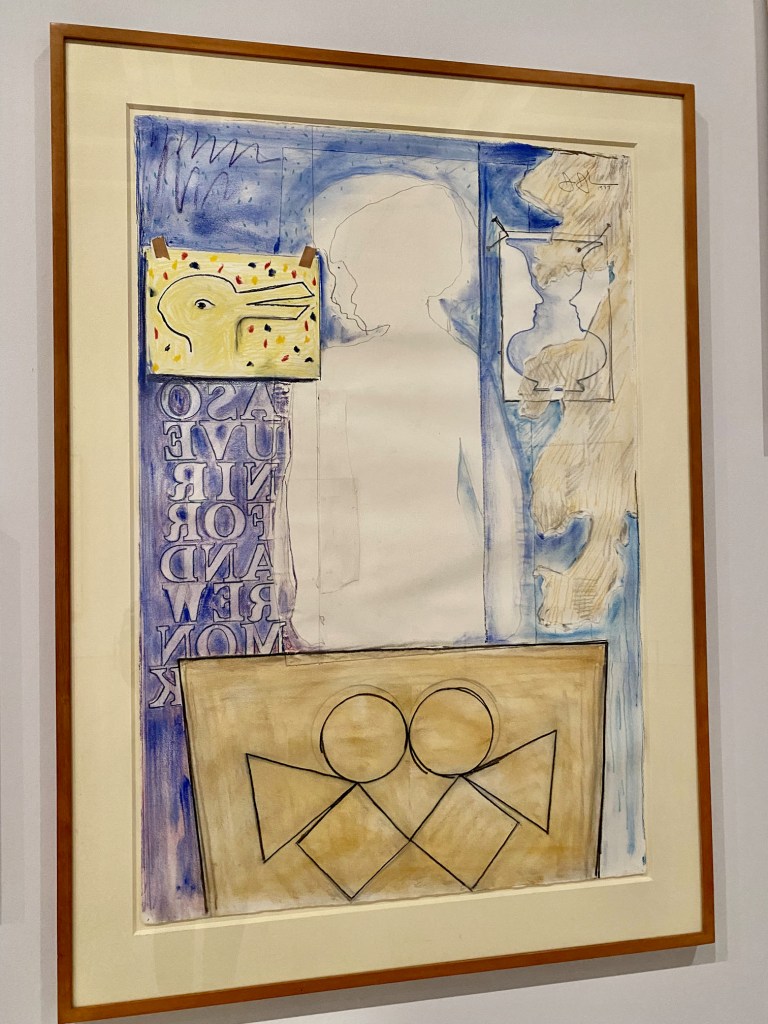

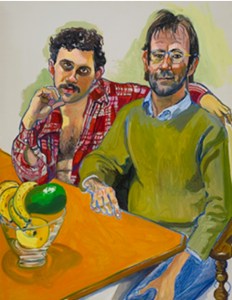

Making American Artists really comes alive by adding 20th century works on the walls. Alongside the Founding Fathers, the portrait section features liberated women, bohemian artists, and proud Black artists with attitude.

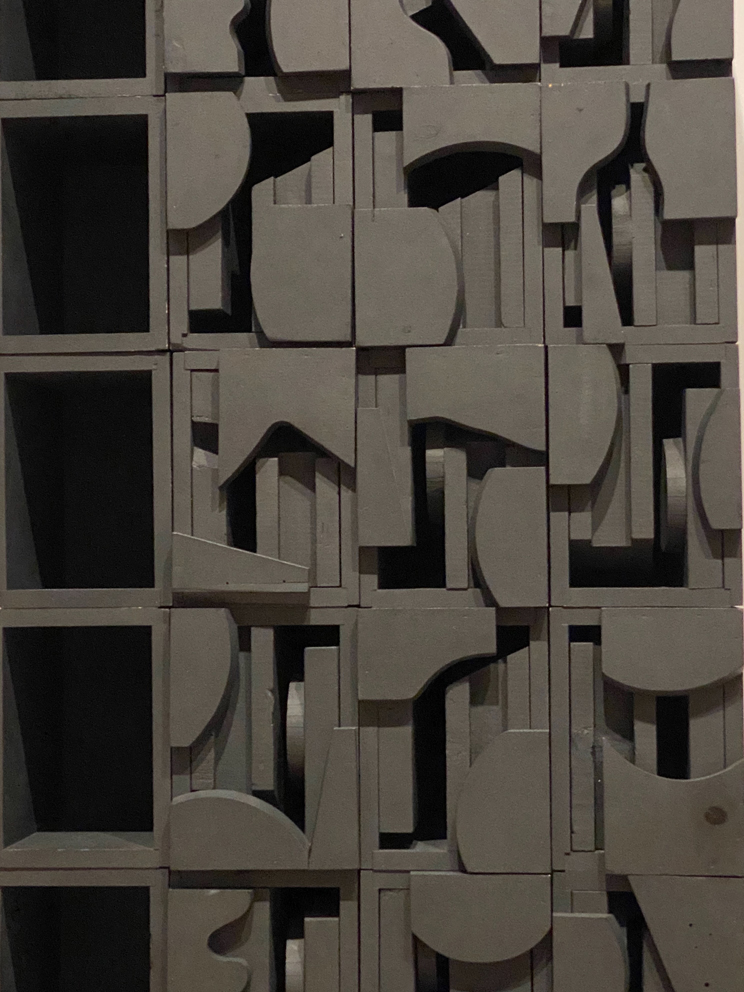

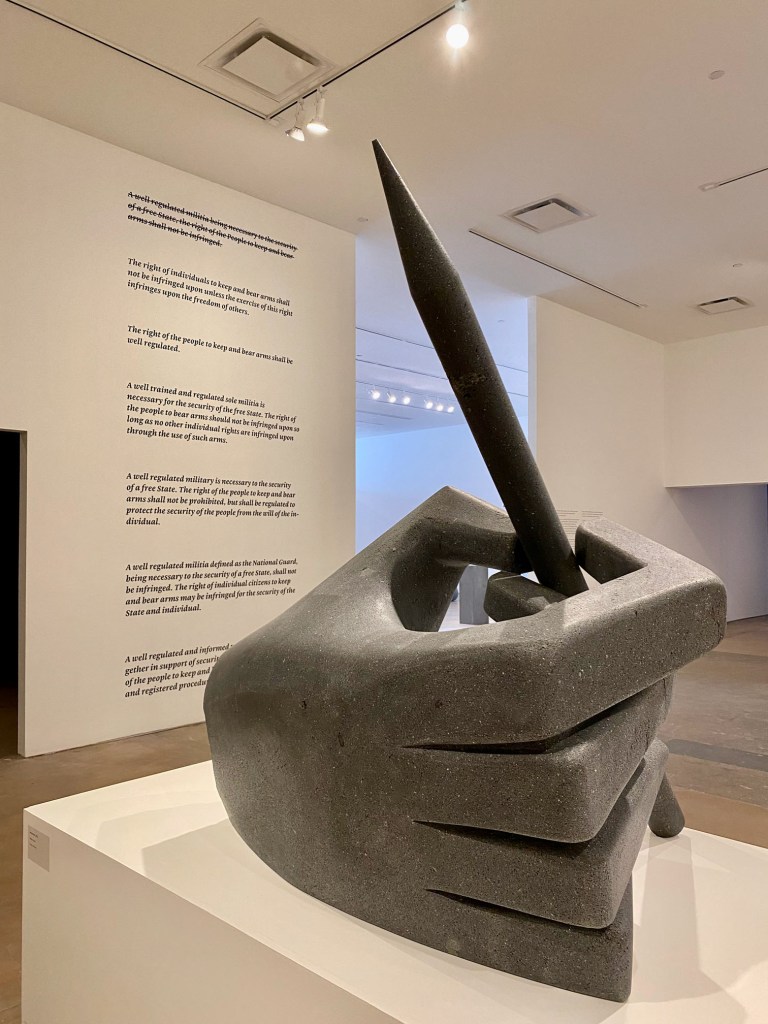

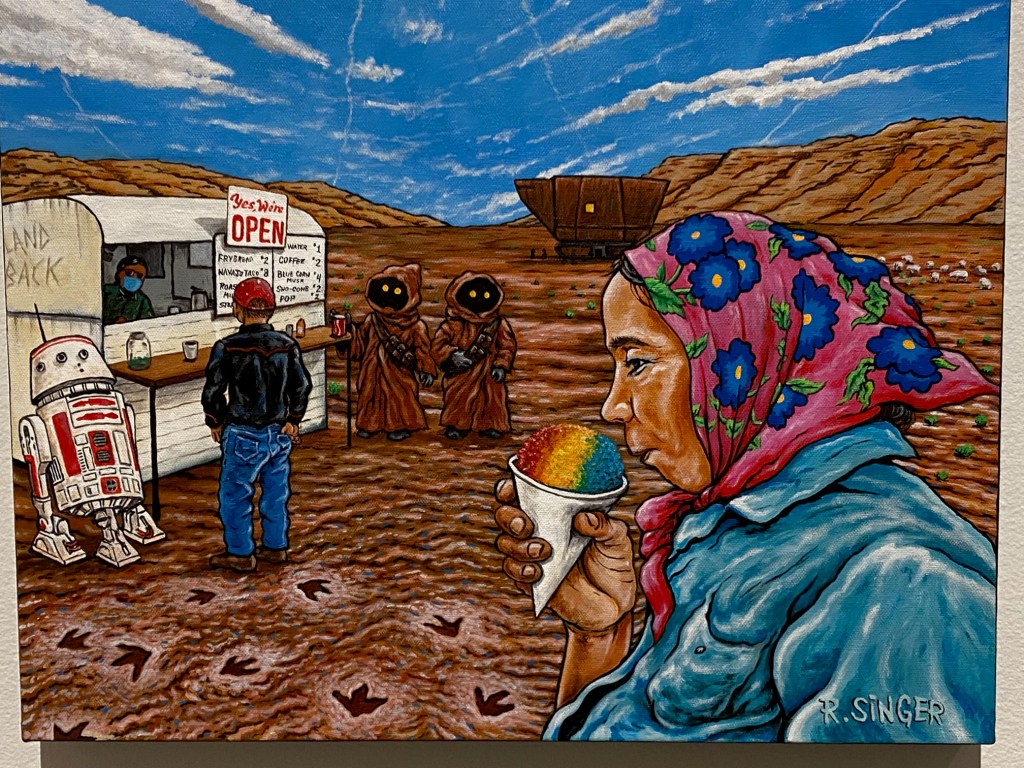

The section of the exhibition on still life focuses on early female painters who made decent incomes from their work, as well as modernist superheroes O’Keeffe and Nevelson. The history painting section presents 20th century show-it-like-it-is artists, like Horace Pippin and Alice Neel.

We’re reminded that many of the great masters of American landscape, like Thomas Moran, got their starts by painting bucolic views of Philadelphia’s Wissahickon and Schulkyll Rivers. Painting Philadelphia’s river landscapes may have even inspired the rise of the Hudson River School.

And it was PAFA that gave Winslow Homer his professional start.

The entire exhibition is a fresh look at American masters who created an astonishing legacy at one of our oldest art institutions and upstarts who never quite got their due. There’s so much to appreciate from this fresh, 21st century perspective!

Earlier this year, Making American Artists was at the Wichita Art Museum. Its next stop is the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma (September 25, 2024), followed by a spectacular road show: Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse (February 2025), the Peabody-Essex in Springfield, Massachusetts (June 2025), and the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia (October 2025).

Don’t miss it. While you’re waiting, listen in to curator Anna O. Marley’s May talk at the Albuquerque Museum: