How do artists – and their art – survive two world wars, an authoritatian dictatorship, and the bifurcation of nation’s premiere art institution? It’s the story told by the must-see exhibition, Modern Art and Politics in Germany 1910-1945: Masterworks from the Neue Nationalgalerie, on view at the Albuquerque Museum through January 4, 2026.

Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie mounted the show to bring never-before-seen works to the United States and tell the story of how modern art became an ideological battleground in Germany during the early 20th-century and how the history of politics, artistic innovation, and social commentary are reflected in the institution’s collections today.

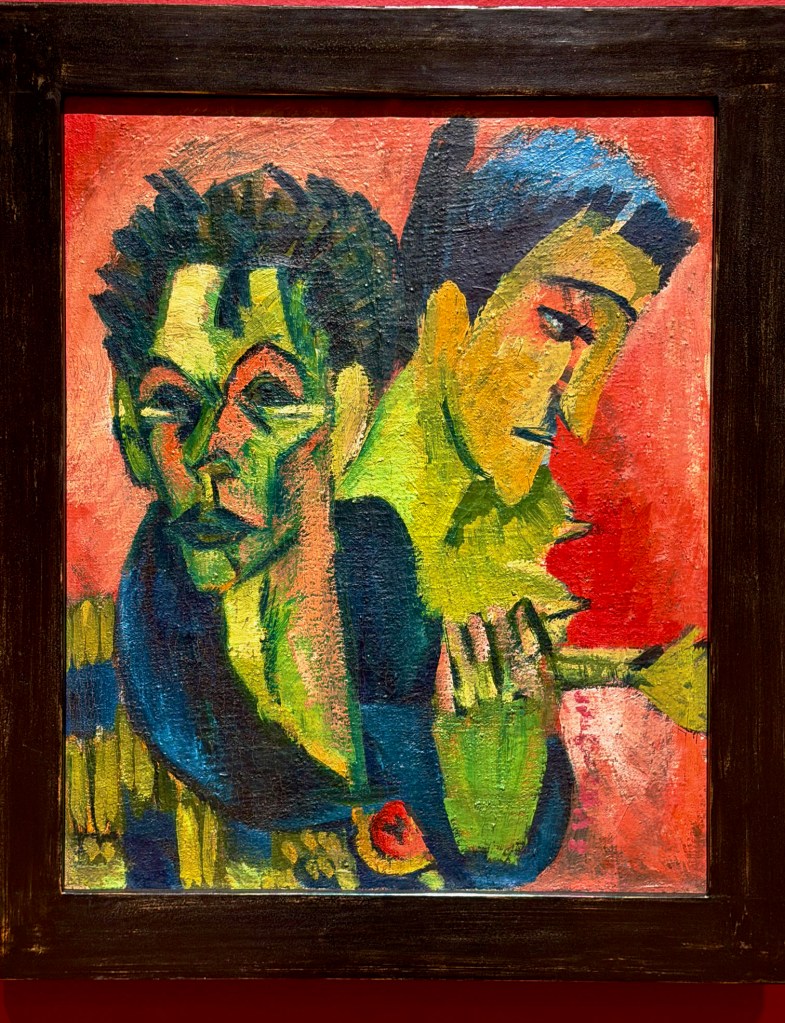

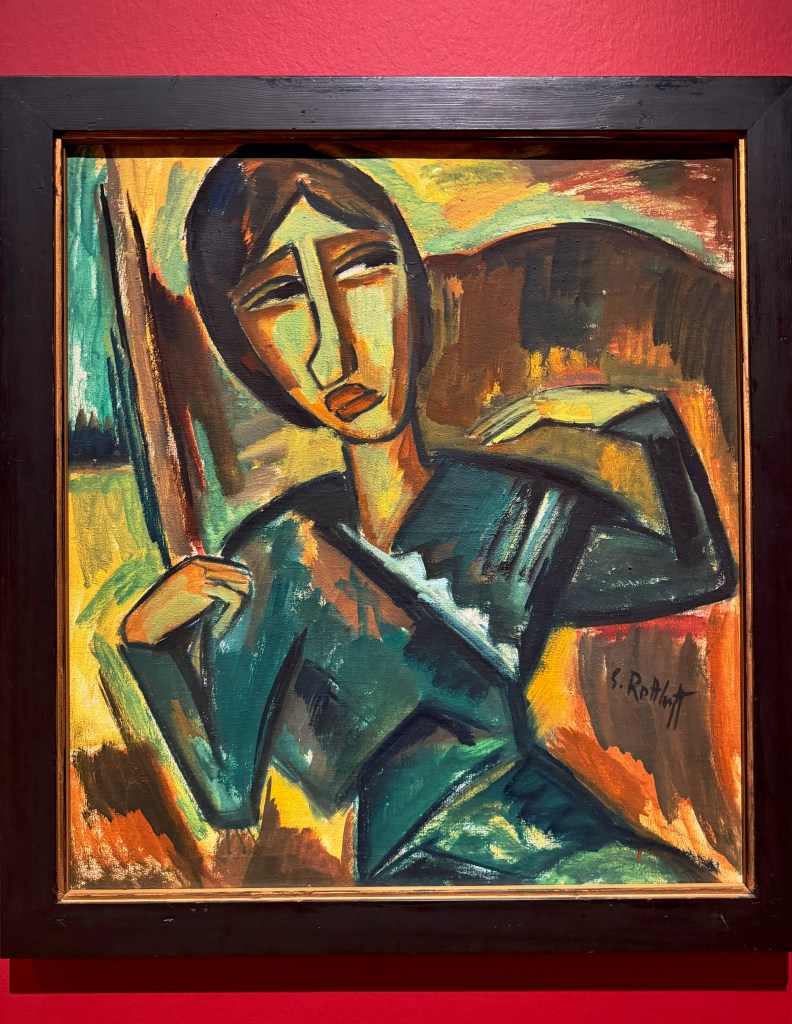

The exhibition opens with works from some of the best-known German expressionists – Kirschner, Pechstein, Schmitt-Rotluff, and Nolde. Slalshes of wild color, sharp angles, and modernist portraits nearly leap out of the frames of paintings, showing the influences of the French avant-garde fauves and Picasso’s angular Cubist planes.

Another section of the exhibition presents portraits of influential German art dealers who brought the best of the avant-garde to Berlin, Munich, Dusseldorf, and other German culture capitals in the early 20th century. Works by influential modernists Picasso, Leger, and Kokolschka hang alongside works by the Russian ex-pats who formed the forerunner group to Die Brücke in 1909 – Kandinsky, Alex Jawlensky, and Marianne von Werefki.

See some of our favorite works in our Flickr album.

In 1911, the German modernists formed Die Brücke – a group that celebrated getting an artist’s inner feeling out on the canvas – not just a formalist declaration against classical painting and historical norms. When World War I broke out, many went to the front. If they survived, they continued painting to process the psychological agony of the War and the economic toll it took on the homeland.

The exhibition also features a gallery full of works that are a logical outcome of experimentation – abstract works by German artists that merge the symbology and energy of Italian Futurism with the riotous colors of Orphism.

Surviving hardship together, the end of World War I only motivated the survivors to come together, form societies and political action committees and keep creating.

Leading up to World War I, it seemed as though modernism would sweep the Continent and become the dominant art style collected by the progressive National Gallery. However, during the 1919-1933 democratic Weimar Republic, art preferences shifted to a highly literal, figurative style dubbed “the New Objectivity.”

This gallery shows the artistic and political shift to realistic portraits with hints of social commentary, depictions of new technology, and a new culture of enfranchised, emamcipated women (exemplified by the museum’s iconic Sonja by Christian Schad).

But over time, the political mood shifted, and the National Socialist Party rose.

Throughout the 1930s, increasingly militaristic and anti-semetic groups formed in Germany, and as the National Socialists came to power, they fired heads of the leading art schools, shuttered the innovative Bauhaus, and banned abstract art and modernism because it did nothing to support their agenda. Artists either went underground (painting in basements) or fled the country entirely.

The exhibition concludes by showcasing works made at the end of the war by German artists reacting to the societal disruption and atrocities. In some cases, banned artists like Karl Kunz were able to paint in secret, wait until the War ended, and emerge to help a divided Germany revive the arts in the post-war years.

Watch the exhibition’s opening lecture by Berlin curator Irina Hiebert Grun, who provides an overview of the Neue Nationalgalerie’s collecting history, responses to the changing politics that affected early 20th century art, how the museum reassembled its collections and personnel after the Nazi-era persecutions.

The war destroyed the buildings and the Allies divided the country, but the story of this museum’s incredible 21st-century renaissance is one for the ages.

After the exhibition closes in Albuquerque, it be on view at the Minneapolis Museum of Art March 7 – July 19, 2026. Don’t miss it!