The artist stories and works presented in Out West: Gay and Lesbian Artists in the Southwest 1900-1969, at the New Mexico Museum of Art through September 2, 2023, shed light on artists who lived a bit more “under the radar” in the early 20th century, compared to the post-1969 era when loud and proud artists unleashed their voices in response to the Stonewall Riots.

The exhibition focuses on how early modernists used “coded” symbols in their work, explores the legacies of two-gendered Native American artists, and introduces mid-century work by mid-century contemporary artists working.

Take a look at our favorites in our Flickr album.

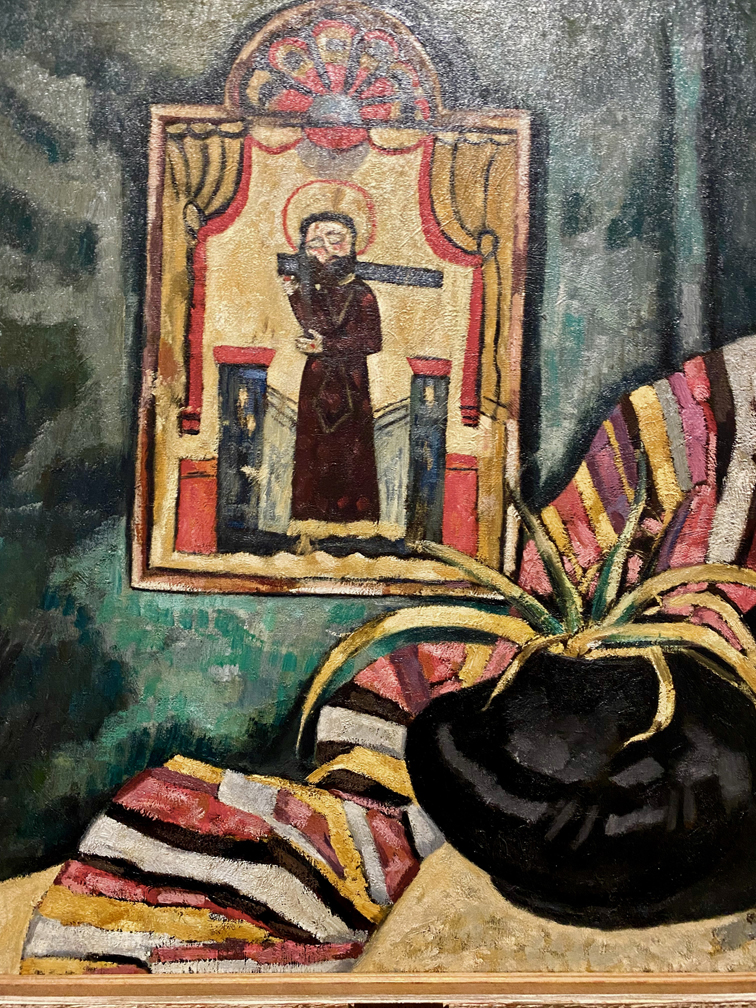

The show opens with works by Marsden Hartley and Russell Cheney – painted 10 years apart (1919 and 1929) that feature items associated with rituals by Northern New Mexico’s Penitentes – Catholic men’s associations that kept faith alive during the 19th century when clergy were scarce in their remote mountain towns.

Hartley and Cheney were captivated by the religious rituals of these mysterious, faithful “brotherhoods” that persevered for centuries, despite periodic bans by New Mexico’s Catholic Church – not unlike the early 20th century gay men’s associations whose underground culture gave rise to “coded” rituals and language.

Hence, these works feature images of the suffering Christ, yucca plants used for self-mortification rituals, adobe churches, and props associated with processional death carts – symbols of religious brotherhood that represent the importance of brotherhood among the early 20th century gay community.

The second portion of the show introduces us to the many painters, photographers, and sculptors who not only drew artistic inspiration from the Southwest, but found communities that welcomed gay and lesbian artists. Works by artists, such as Agnes C. Sims and Cady Wells, are paired with portraits by a Southwestern who’s who of modern portraiture and photography – Will Shuster, Laura Gilpin, Ansel Adams, and Anne Noggle.

There’s even a “portrait” stitched by maverick Cady Wells of his very best friend, modernist Rebecca James. Well known for his expressionist paintings and his large collection of Northern New Mexican religious art, Wells subversively went all in on petit-point – an art form traditionally associated with “women’s work” and beloved by Ms. James.

This section also includes the stories of important two-spirit Native American artists – individuals who are born “male” but who take on spiritual and other tribal roles traditionally associated with women. The first is We’wha, a respected 19th-century expert in and advocate for Zuni arts and traditions– a favorite of Smithsonian anthropologists who demonstrated weaving in D.C. and even presented a special work directly to President Grover Cleveland as a wedding gift.

Another is R.C. Gorman’s portrait of Hosteen Klah, a Navajo two-spirit, one of the the Wheelwright Museum’s co-founders. Gorman, one of the best recognized and flamboyant 20th century contemporary Native artists, excelled in colorful mid-century works. Gorman made history in Taos by opening the first Native-owned gallery in the United States.

The final portion of the show includes two works by female rule-breakers. The first is a rare Agnes Martin 1954 abstract-expressionist work typical of her experimentation prior to her acclaimed grid series. It’s much more aligned to the biomorphic symbolism of early Pollack and Rothko – reflecting what was happening earlier in her New York career during the heyday of the Cedar Street Tavern crowd.

Second ia a never-before-seen 1997 installation by feminist-art innovator Harmony Hammond, who was also represented in this year’s Whitney Biennial. Hammond, who curated one of Santa Fe’s first LGBTQ exhibitions back in 1999, used to travel backroads of the Southwest, finding abandoned towns and homesteads and collecting left behinds. In this show, she presents What Have You Done With Our Desire, a mixed-media piece using ancient kitchen linoleum – an allusion to circumstances leading to repression of gay women’s sexuality.

For more about these and other artists, listen to curator Christian Waguespak’s talk about LGBTQ artists in the Southwest at the Harwood Museum in Taos.