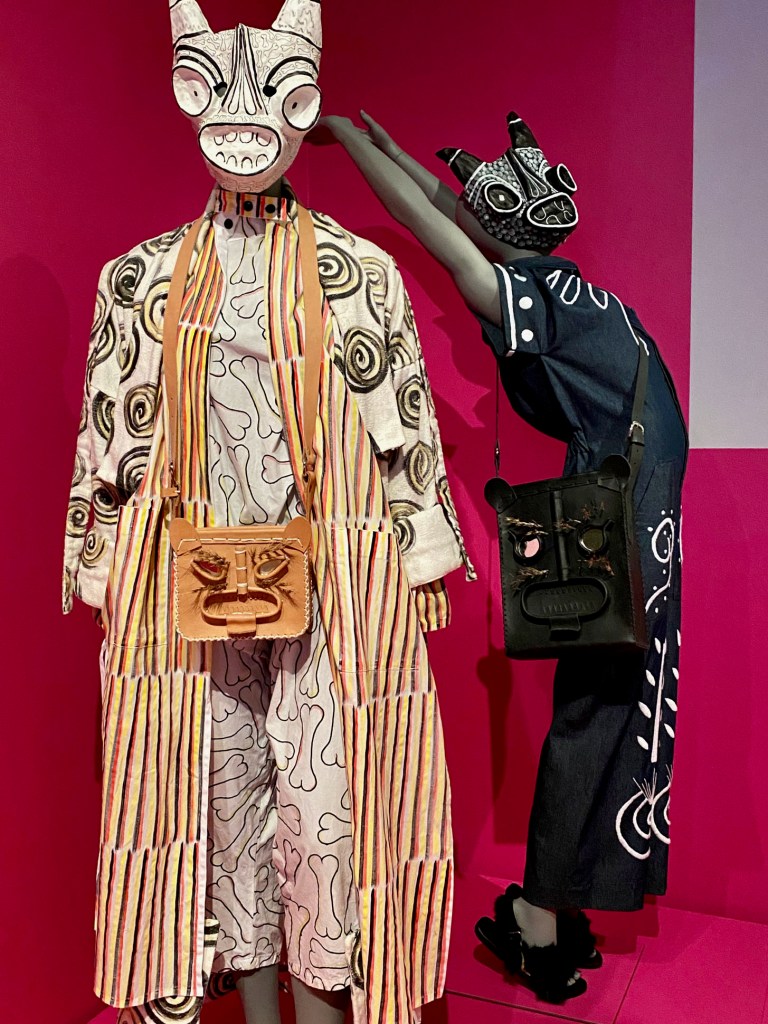

It’s not often you find yourself surrounded by vibrant contemporary art that directly connects you to dreams and stories that have been told and retold for tens of thousands of years. Meet some exceptional visual storytellers from nearly twenty Australian regions in Eternal Signs: Indigenous Australian Art from the Kaplan and Levi Collection, on view at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno through November 2, 2025.

This exhibition showcases well-known and emerging artists in different geographic areas of Australia’s north coast and interior desert. See our favorites in our Flickr album and consult the map to locate the communities where the featured artists work.

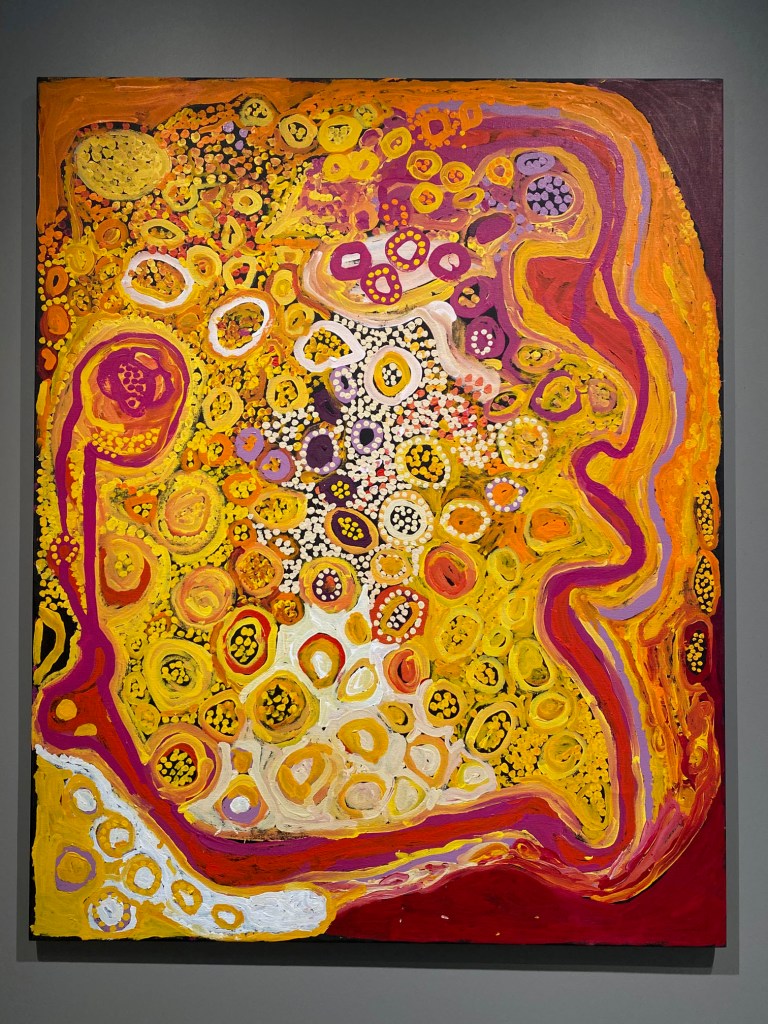

For thousands of millenia, the indigenous groups in Australia have created rock art, painted spiritual images on eucalyptus bark, and documented their “dreams” – a mix of creation stories, confirmation of people’s integration with the land and animals, and everyday life. These visual affirmations present a simultaneous representation of past, present, and future, hence the term “eternal signs.”

Stories, images, culture, dreams, and language differ greatly among Australia’s 120 indigenous groups. (We’ve indicated each artist’s geographic region and particular language after their name.)

From Arnhem Land in the north, Paddy Fordham Wainburranga (Rembarrnga) from Wugularr, Northern Territory is one of the best-known artists shown. Growing up in the bush, Paddy was eleven when he first encountered anyone outside his traditional community. In the 1970s, he moved to Maningrida, a government-sponsored settlement, and began painting at the Arts & Culture Center. Paddy’s work often depicts ancestral spirits that he first encountered in rock art.

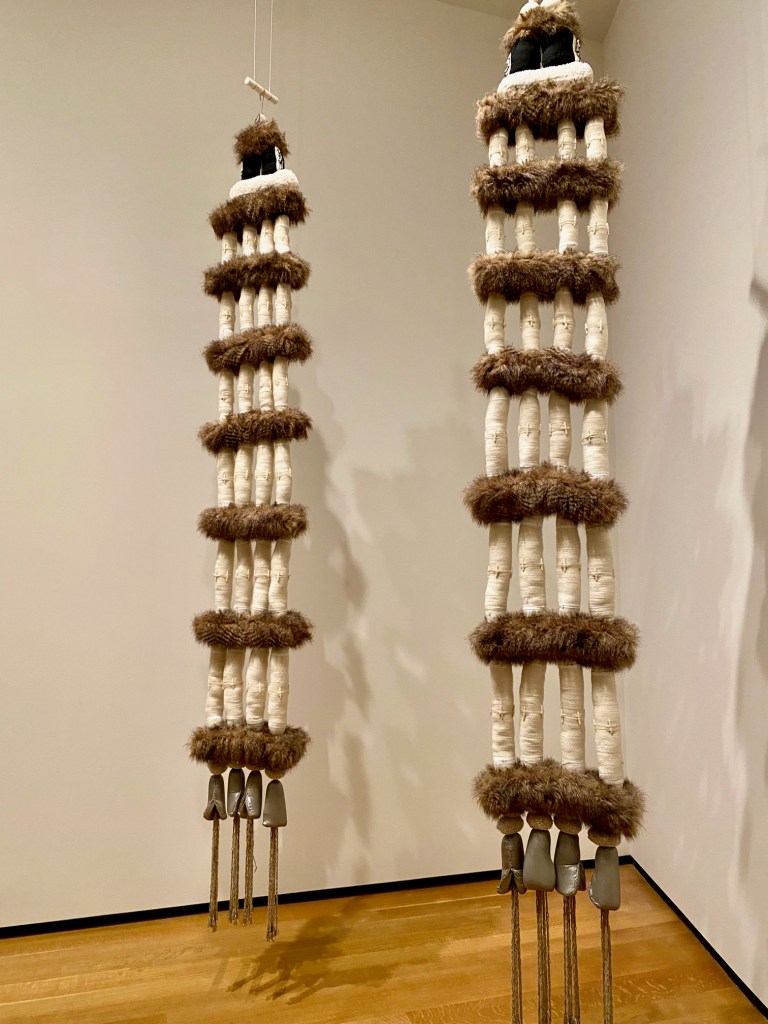

John Bulunbulun (Ganalbingu), another Maningrida Arts & Culture Center artist, also starts with traditional dreams and forms – for example, he uses a traditional hollow-log coffin as a basis from which to sculpt a three-dimensional dream about the long-necked turtle creator. Take a look.

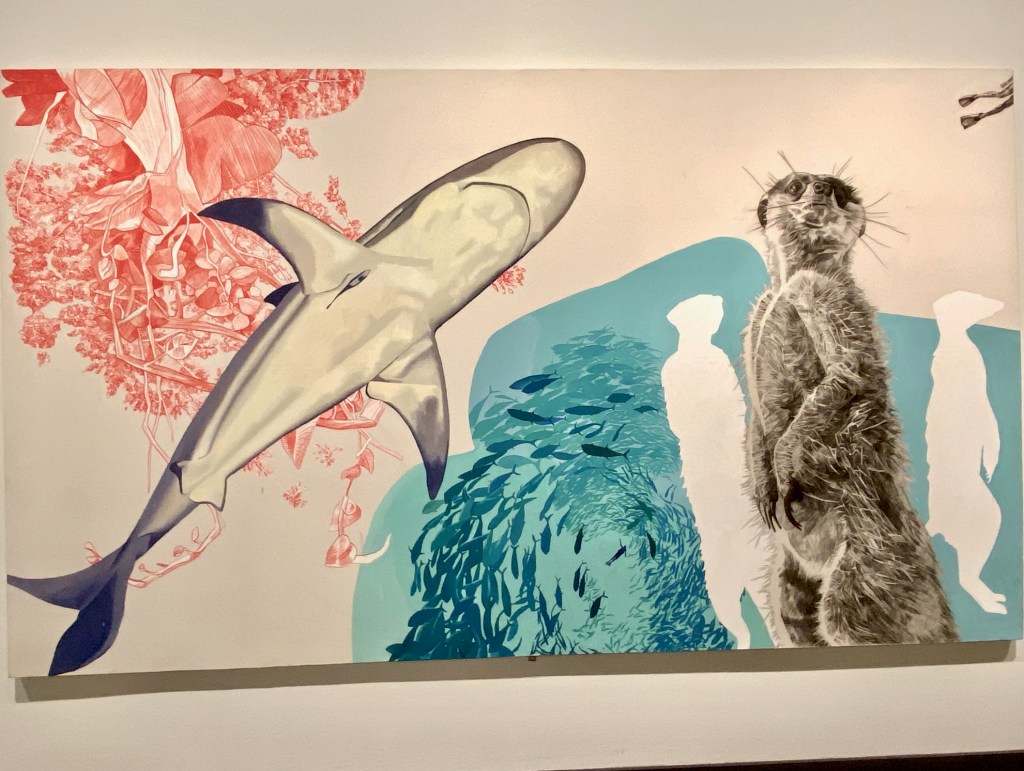

More recent work by Yirrkala artists in East Arnham reflect ecological concerns and the clans’ interest in protecting ancestral lands. A dramatic sculpture by Guynbi Ganambarr (Naymil) reflects the rich, majestic, and spiritual coastal life of the Grove Peninsula. A masterful wall piece by Djambawa Marawili (Madarrpa) is one in a series that he’s used to affirm his people’s land and sea rights – even used as legal evidence in court cases challenging indigenous rights to land and sea, demonstrating the deep, spiritual meaning behind their claims.

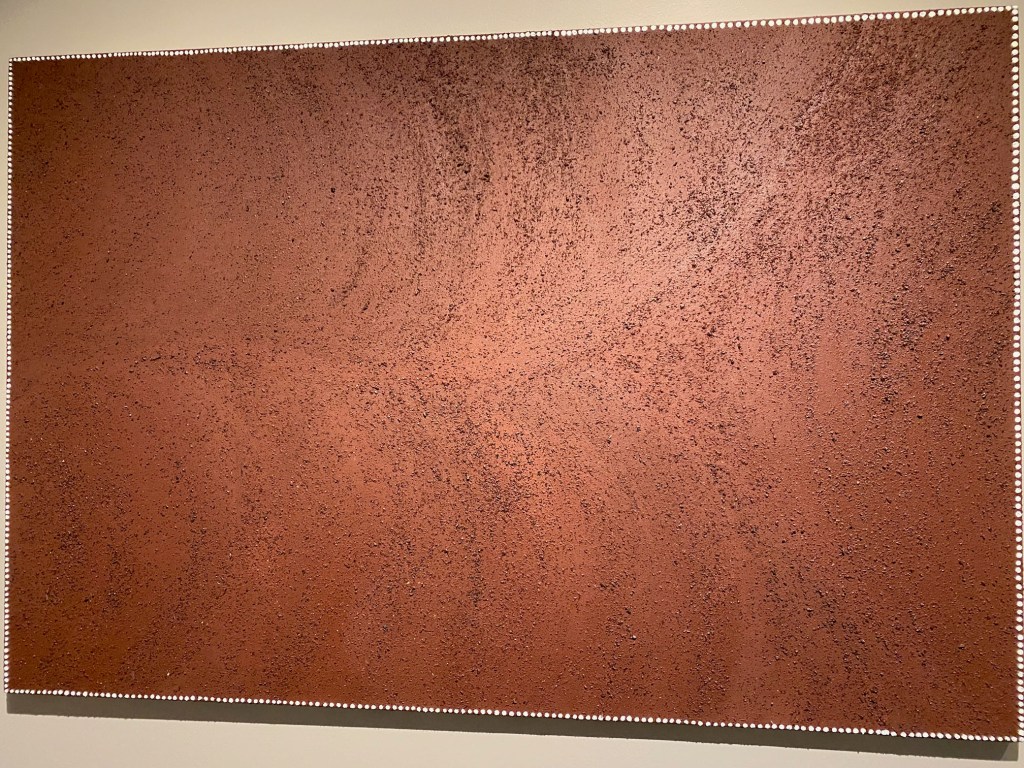

Here are two works by the award-winning Petyarre sisters from the area of Utopia on the border of the Tanami Desert in central Australia – an area that began to achieve acclaim as an art center in the late 1990s with dot paintings referencing the landscape and women’s expertise in bush medicine.

We have to give a big shout-out to Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi for donating over 70 of these amazing artworks to the Nevada Museum of Art. Their passion shows!

In case you aren’t able to enjoy this insightful, beautiful show at the Nevada Art Museum, art lovers will be able enjoy The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art from the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne as it tours across the North America. Right now, The Stars We Do Not See is scheduled for the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. through March 1, 2026.

The Stars We Do Not See will travel to the Denver Art Museum (April 19 – July 26, 2026), Portland Art Museum (September 2026 – January 2027), Peabody Essex Museum in Salem (February – June 2027), and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto (July 2027 – January 2028).