The local artist honored in Taos with a lifetime retrospective lives and works only 18 miles from Georgia O’Keeffe’s famous home in El Rito. But their work, lives, purpose, and legacy couldn’t be further apart.

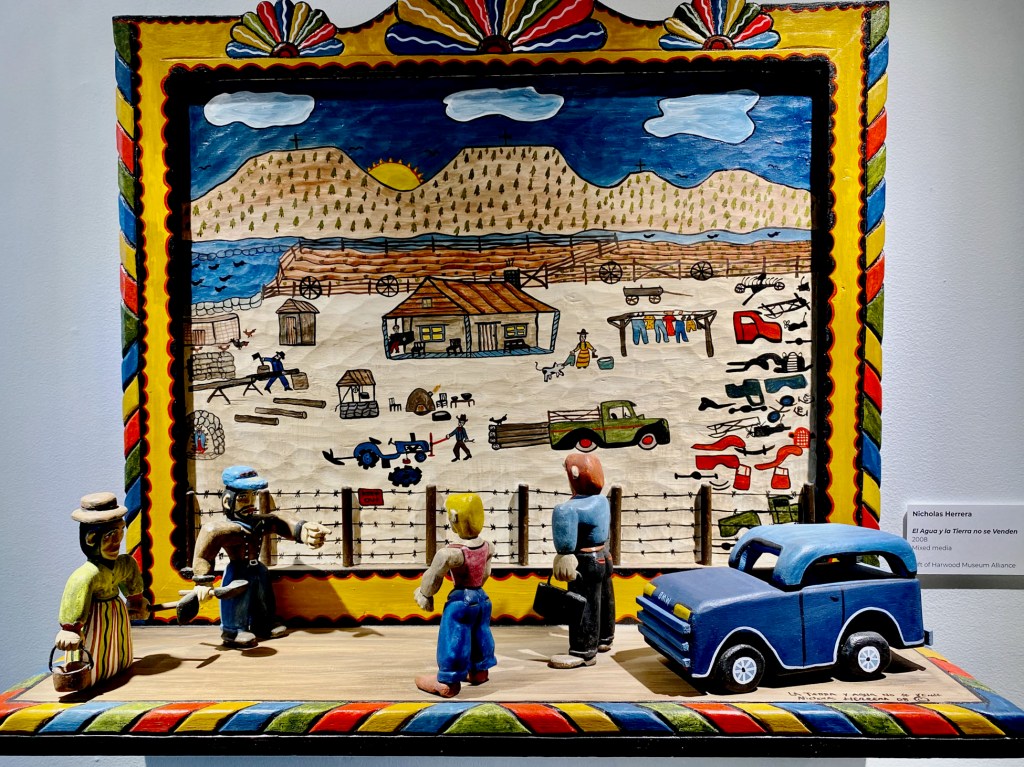

Nicholas Herrera: El Rito Santero, on view at the Harwood Museum of Art through June 1, fills three galleries with work by a New Mexican wood carver who not only pays tribute to saints and ceremonies important to the nearby rural Hispanic communities, but also channels politics, social commentary, lowrider culture, and pressures of modern life in a mixed-up world into his craft.

It’s a colorful, irreverent, heart-felt tribute to the people, places, religion, and culture of the rural high hills that he calls home. And here’s Herrera’s self-portrait – the namesake of this engaging retrospective.

At first glance around the gallery at the top of the back stairs, Herrera’s work seems firmly situated in the tradition of the last 400 years of northern New Mexico saint-carving. Since the 1600s, when Spanish farmers first colonized these remote hills, the faithful relied primarily on local artists and carvers to decorate home chapels, churches, and shrines.

Herrera’s work is the 20th century version. There’s a grand, colorful painted altar honoring his brother in which a pantheon of Catholic icons gazing benevolently upon you. You’ll also meet his special icon – a bright, enigmatic Lady of Guadalupe.

In a small, dark room you’ll experience a powerful home altar, filled with hand-carved spiritual tributes, surrounded by candles and and all manner of other-worldly retablos.

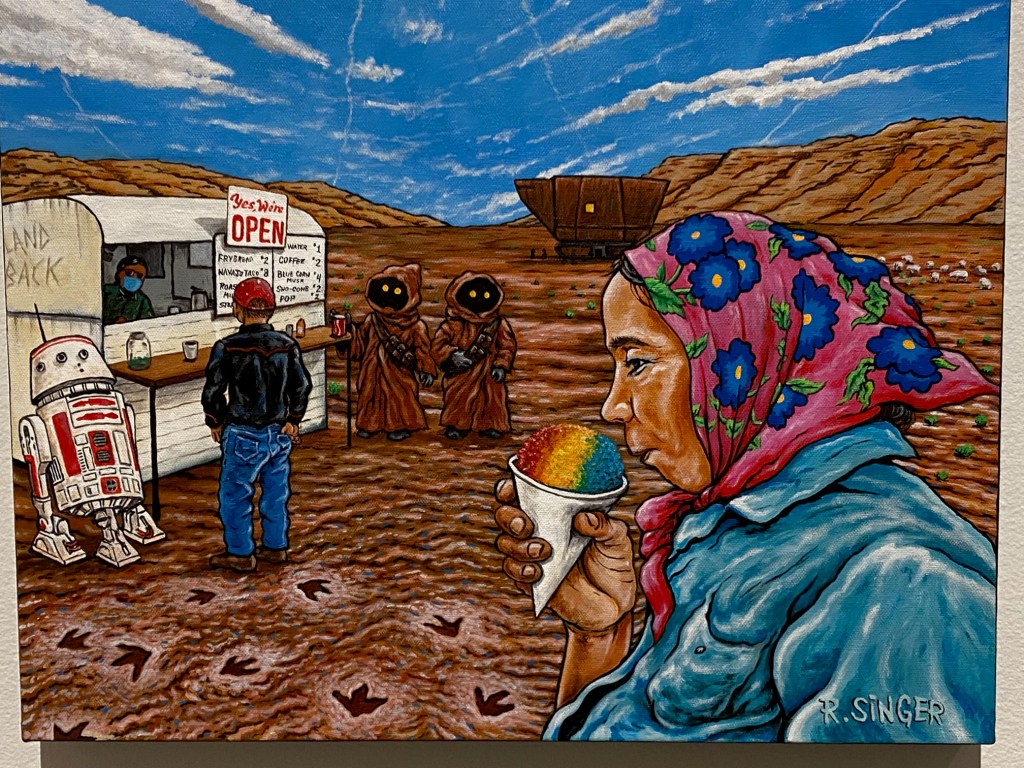

But the next two galleries, you’ll encounter work using these same materials and techniques, but reflects life-changing events in the artist’s life that are mashed up with ancient spiritual traditions – Jesus in the back of a speeding cop car, Herrera’s own near-death experience in a car crash when he was in this twenties, and a crazy lights-flashing slot machine promising allures that only the Devil can love., or aerial views of old Spanish valleys.

Like all great artists, Herrera is inspired from life events and the world around him – reflections about his growing up and home life, land-use and traditions in his community, and issues ripped from the headlines, like the terror of transporting Los Alamos nuclear waste or issues with the border patrol.

Used car parts, toy parts, and other stuff from the junkyard “tell” Herrera how and where he might use them. Lowrider culture is an important source of price in Northern New Mexico, so it’s not surprising that he’s channeled that part of the local experience into his work, too.

See some of our favorite works in our Flickr album, and meet the artist himself in this short video profile created by the Smithsonian American Art Museum: