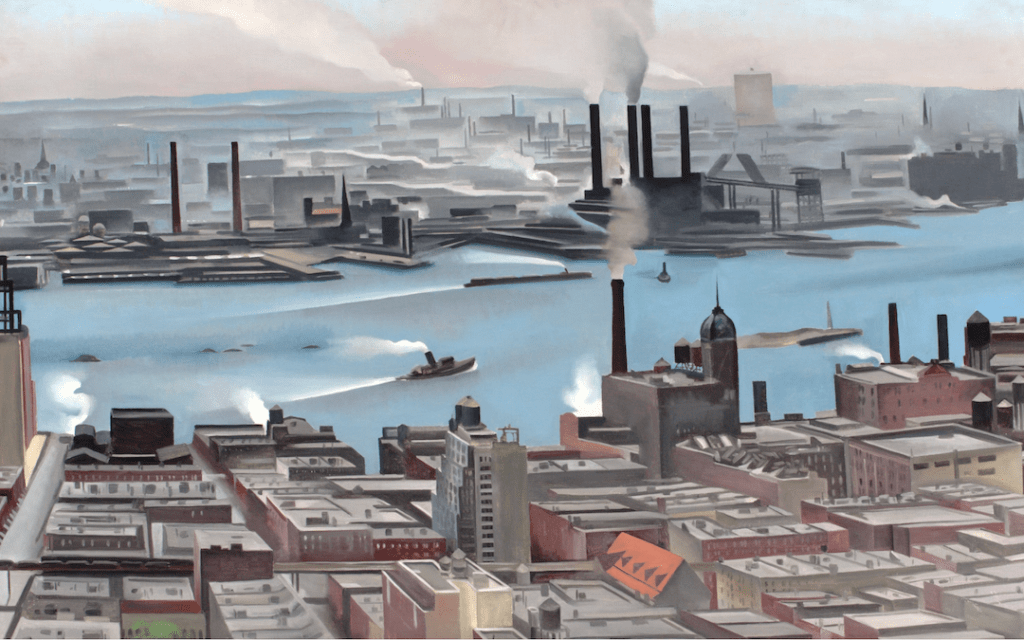

Six years before she became transfixed with the drama of the colorful New Mexico desert, Georgia O’Keeffe began translating another magnificent, magical view from her skyscraper home in Manhattan. You can see all her transformational aerial cityscapes in Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks” on view at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art through February 16, 2025.

Created by the Art Institute of Chicago, the show assembles Georgia’s breakthrough city paintings and puts them squarely into the context of her better-known nature close-ups and other modernist takes – just the way she wanted it.

Listen to the Art Institute curators talk about Georgia’s approach to New York landscapes, her life in the city’s Roaring Twenties, and what inspired her walking Manhattan’s grid at a time of of such transformational urban change:

As a total modernist, Georgia couldn’t wait to move into the Shelton Hotel, a brand-new skyscraper, with her brand-new husband (Stieglitz) in 1924. As half of New York’s art-world “power couple” it’s most likely that Georgia was one of the first women to enjoy high-rise living in Manhattan.

The Shelton (still there at Lexington and 49th Street) was an apartment-hotel built in Midtown around Grand Central. Although it was first envisioned as a men’s residence, the marketing team soon pivoted a more expanded market with newspaper ads that would attract women, couples, and artists!

Read more about the Shelton, Georgia’s life there, and see 1920s photographs on the Art Institute’s blog post.

Georgia and Alfred moved in, captivated by the views of the East River and rapidly changing Manhattan skyline, where new skyscrapers were popping up like daisies. Alfred took photographs and Georgia recorded ths shifting light, atmosphere, and moods of the rapidly changing landscape.

Courtesy: New Britain Museum of American Art.

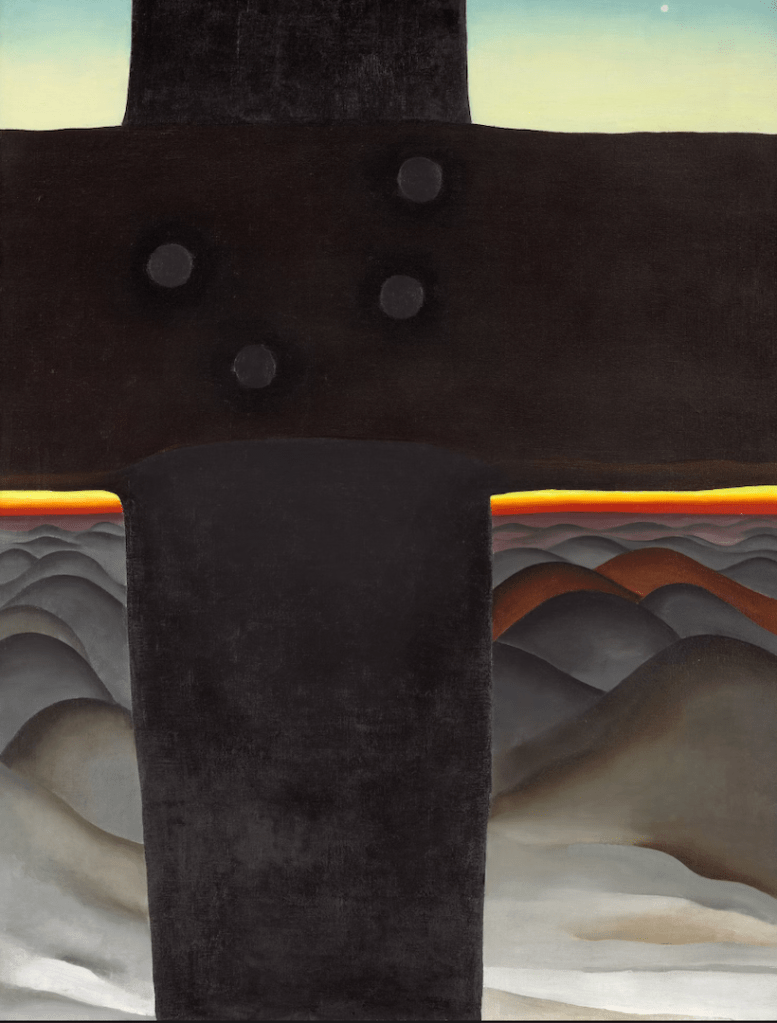

As the exhibition demonstrates, Georgia didn’t limit herself to urban landscapes at the time. She was still depicting the natural world, but was determined to channel the rising modern city. At the time, Alfred and her fellow artists strongly discouraged her from displaying her urban work, arguing that painting cityscapes was “best left to the men.” You can just imagine what our Georgia thought about that! Naturally, it was full steam ahead!

Before Google Street view, Georgia walked the Midtown Grid, exploring (and remembering) her neighborhood streets as they transformed into skyscraper canyons. More high rises! The Empire State Building! Rockefeller Center!

Who knows if Georgia ever experienced Manhattanhenge, but she certainly enjoyed the verticality and sky views between the buildings. A nature-lover, modernist, and virtuoso painter!

Despite Stieglitz’s misgivings about her city paintings, when she finally had her annual one-woman show at his gallery, her city painting was the first work that sold!

The curators have hung some of Georgia’s paintings just as she displayed them – side-by-side flower close-ups, other nature-inspired works, and City views – to provide the full experience of a modern woman’s mastery.

For more, here’s a longer discussion about Georgia rip-roaring 1920s life and work by one of the Chicago Art Institute curators for Georgia O’Keeffe Museum members.