With his traveling valise sitting in the center of the introductory gallery and a map nearby, you understand instantly that superstar artist Marsden Hartley was a man on the go.

Marsden Hartley: Adventurer in the Arts, on view at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe through July 20, 2025, uses his personal possessions, works painted on two continents, and non-stop itinerary to demonstrate how landscape, life, and modern-art legends led him to create an epic body of work.

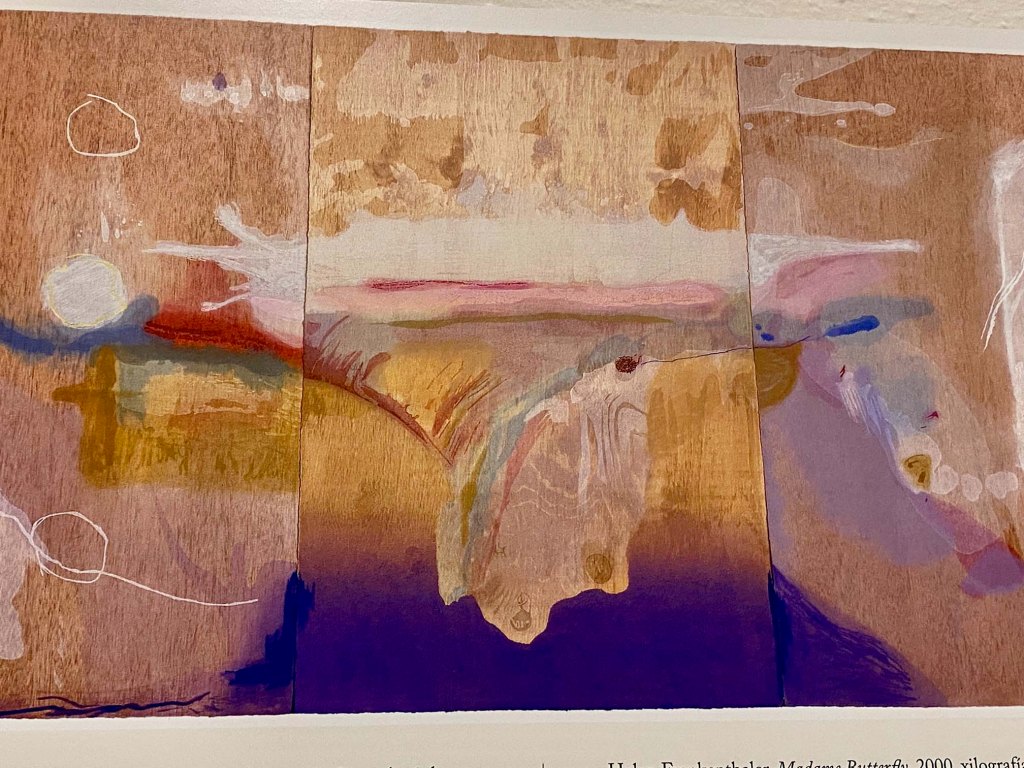

Take a look at our favorites in our Flickr album.

Looking around, there’s a wall of Maine mountainscapes he did in his thirties, a painting done just after Stieglitz sent him to Paris to soak up the vibes in Gertrude Stein’s salon, his accessories of rings and cigarette cases from Berlin in the 1920s, a Fauve-ist impression of Mount Saint-Victoire at Cezanne’s old stomping grounds in Aix, and photos of him and his dog at his Maine studio in the 1940s.

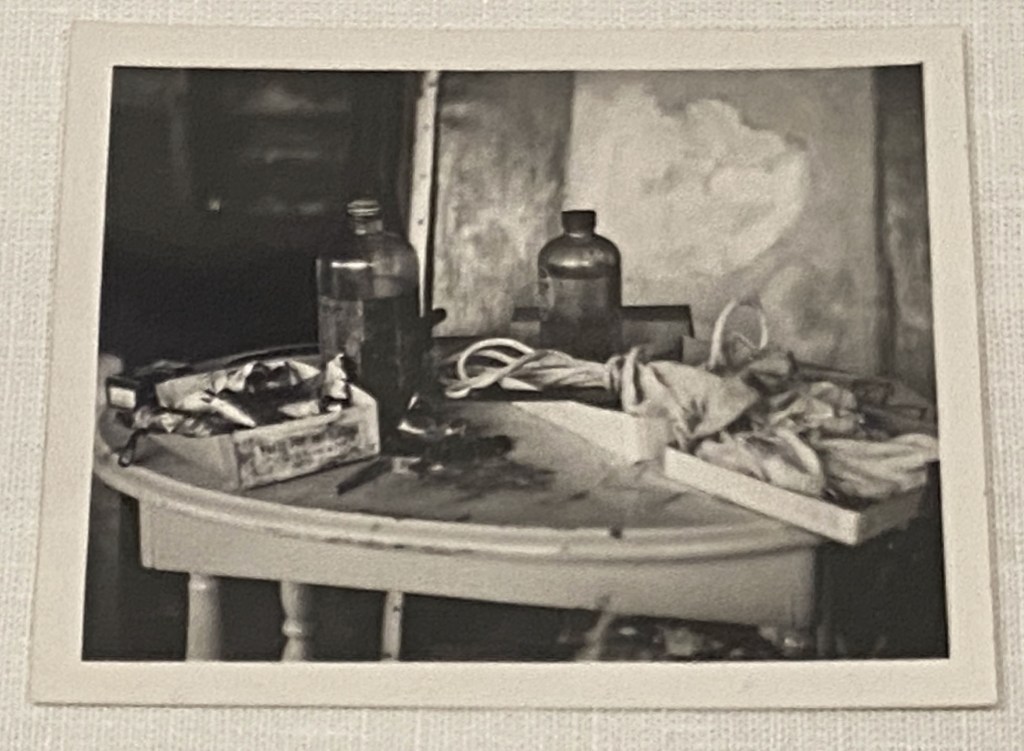

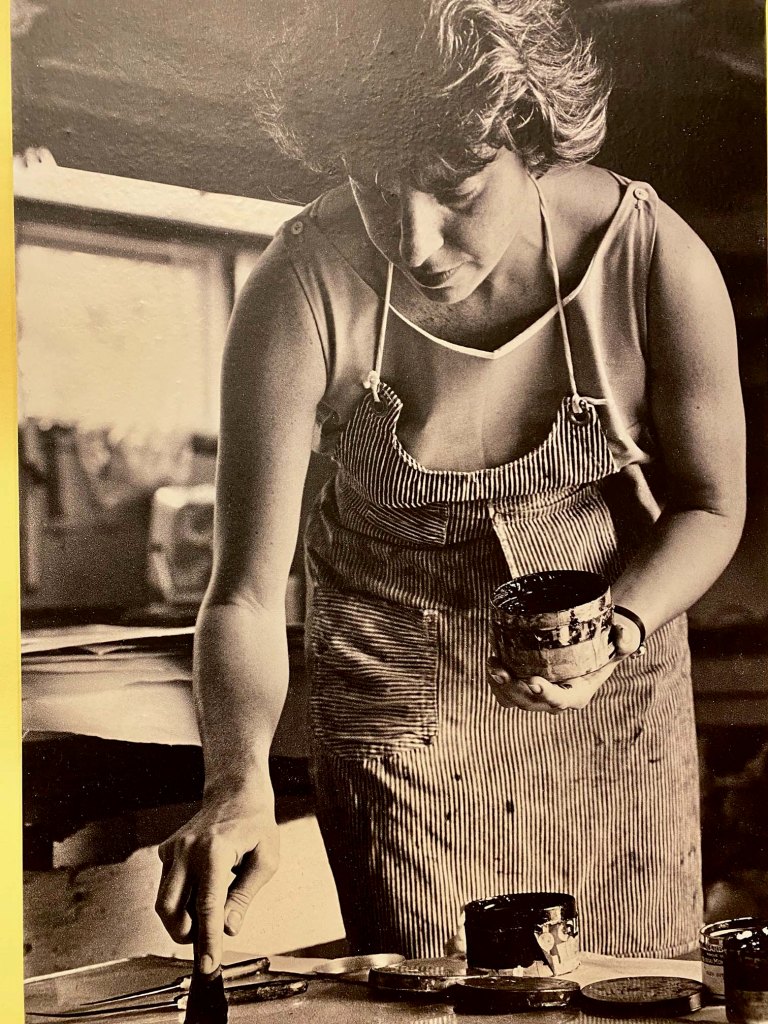

The exhibition merges Hartley’s paintings from the Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection with items donated by his favorite niece to Bates College in Maine – items he collected as he traveled; sketches and stuff sent to his neice; his camera, books, and snapshots; his studio paintbox, and other personal art. Together, the exhibition tells a story of innovation, personal journey, and relentless art making.

Hartley emerged from a hardscrabble childhood to see, feel, and experience art, nature, and transcendental spiritualism in New York, Boston, and Maine in 1890s.

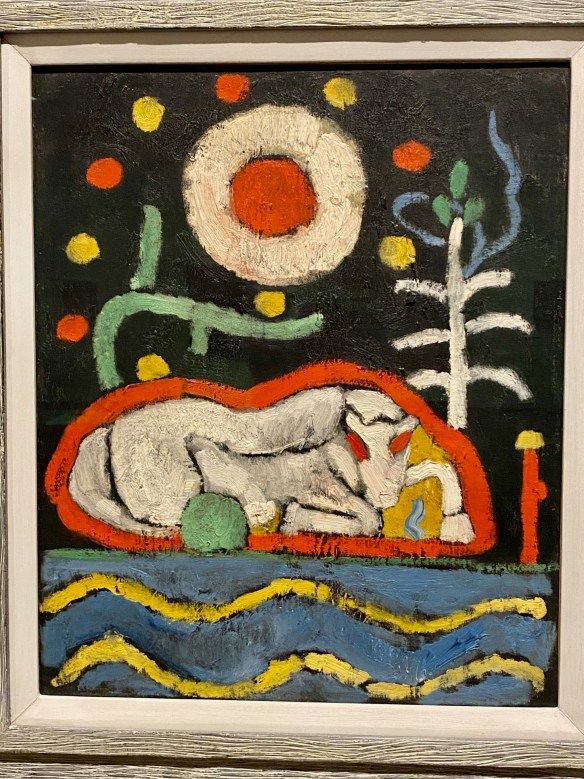

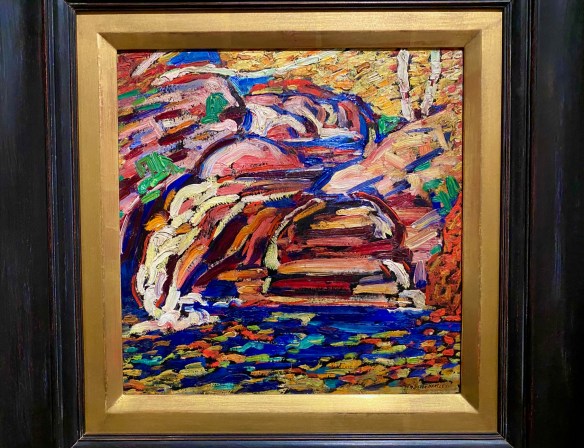

He loved painting mountains and depicted water, earth and sky as a color-filled flat plane filled with jabbing brushstrokes – an approach that stuck with him throughout his life as he journeyed through New Mexico, the Alps, Mexico, and back in Maine.

By the time he was in his early thirties, he had shown his landscapes to The Eight, knocked on Stieglitz’s gallery door, and got a one-man show (and a dealer for the next 20 years) at 291, the hottest modern art gallery in America.

Getting to Europe in 1912, the color, cubism, and symbolism of the Blue Rider, Matisse, and Picasso made his head spin. His German friends introduced him to Kandinsky’s book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. He went out of his way to meet the man himself, and his painterly wheels turned.

The second gallery presents a large work from his Cosmic Cubism series – an airy, dreamy arrangement of signs, spiritual symbols, colors, and planes – along with drawings from his Amerika series, based loosely on Native American symbols and other abstract shapes. On view for only the second time in the United States, Schiff is a dazzling creation drawing signs and symbols from Native American and Egyptian cultures that spill out onto the painted frame.

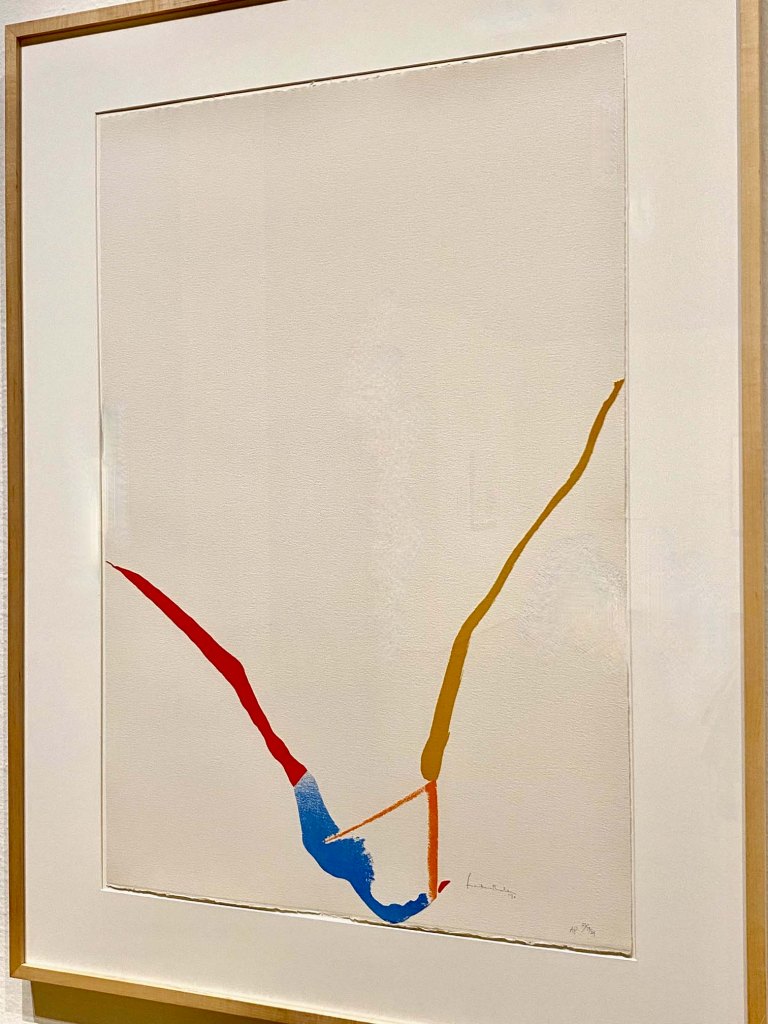

Up to this point, Hartley’s only encounter with indigenous American culture came from visits to ethnography museums in Paris and Berlin, but that would soon change. The advent of World War I tore apart the avant-garde, his social circles, and the direction of his work. Although these Berlin abstractions were long considered by late 20th century critics to be the high point of his career, Hartley abandoned this artistic path when forced to return to the United States, started over, kept wandering, and went back to landscapes and still lifes to discover his “American” expressionist vision.

The exhibition does not unfold chronologically. Instead, it shows how much friends, place, and spiritual encounters affected him.

Near the Berlin abstractions are highly expressionist 1930s rockscapes from Maine and pointy Alpine peaks from his return to Bavaria. There’s an example of his stripped-down 1916 “synthetic cubist” work in Provincetown, a 1917 New England still life painted in Bermuda when he was budget-bunking with Demuth, and a red-saturated still life that is a therapeutic tribute to his Nova Scotia friends who died at sea in the late Thirties.

In the middle of this gallery are vitrines with highly personal, everyday stuff from a painter who never settled down, stayed on the move, and always kept creating.

Here’s his camera, a scrapbook of personal photos, his 1923 published book of poetry, a few books from his library, and a little toy and pressed flowers sent to his niece.

Except for the Provincetown piece, all the surrounding paintings have direct, bold outlines, vivid colors, and vigorous, unglamorized visions – a fitting prelude to the last gallery of New Mexico landscapes.

The final gallery provides a panorama of landscapes, plus a dramatic image of a ridge of Mexican volcanoes. Hartley only spent part of

1918 in Taos and Santa Fe, where he traversed the hills, attended Pueblo ceremonies, and wrote about the indigenous culture. He also completed his El Santo still life with a black-on-black ceramic vase, a striped textile, and a Northern New Mexican retablo of a suffering Jesus.

But it might be a surprise to learn that all of the Southwest landscapes were painted in Berlin in the 1920s – fittingly called his New Mexico “recollections” – or in Mexico in the 1930s.

Floating clouds, expressive lines, and abstracted mountains – all from his vivid mind and recollections of spiritual and physical experiences long past. In the 21st century, increasing numbers of art historians and artists have looked to this phase of Hartley’s work for insight and inspiration – bold brushwork, expressive memory, and both a spiritual and emotional creative process.

Toward the end of his life, the accolades, awards, honors, and retrospective exhibitions came his way, but Hartley remained the hardscrabble “painter of Maine,” barely interested in cashing the checks.

His niece, who preserved her uncle’s posessions and legacy after his death in 1943, took a train trip to New Mexico for the first time to see the landscapes that so inspired her uncle. Upon emerging from the train at the stop near Santa Fe, she looked up to take in the big, dramatic, cloud-filled sky. Thinking of all her uncle’s landscapes, she said, “Those clouds…I’d recognize them anywhere!”

If you see this show in Santa Fe, you will, too.