Amidst the light, glamour, glitter, and mystery sending shock waves and awe through the masses crowding into the Brooklyn Museum’s show, The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk, a hush falls as each person realizes they’re only an arm’s length away from the Icon’s icon. Lovingly crafted from vintage lame, JPG and Madonna had no idea (according to Madonna) what a sensation their underwear-as-outerwear statement would create in fashion, performance, pop, and culture when JPG designed her get-ups for the Blond Ambition World Tour. Get out to Brooklyn to experience this über-tribute before Feb 23.

Madonna’s lent her JPG corsets to the section of the show where the walls are covered in quilted satin, and JPG dug into his archives, too: You’ll see the series of illustrations he did to show the looks he would create for the tour, as well as JPG’s personal Polaroids shot during the initial fittings. If you’re very quiet in this part of the show, you’ll also hear visitors gasp when they realize that they’re looking back at artifacts from 1990!

This genuinely theatrical tribute to JPG is chock full of corsets and cages made from silk, leather, raffia, wheat, and enough other stuff to win the Unconventional Materials challenge hands-down. O ye of Project Runway, worship at the mannequins of the Master!

At the entrance to the show, there are two small photo portraits of JPG taken by Mr. Warhol himself. They’re at a dance club in 1984 and JPG is in one of his Boy Toy collection outfits. Andy is quoted as saying, “What he does is really art.” It’s a curatorial anointment that offers a subtle, quiet, reflective moment to what you’re about to experience.

Dealing with the recent blizzards would have been more fun if you had shopped JPG’s Voyage Voyage ready-to-wear collection (2010-2011). These are styled with pieces from older collections.

Room after room of gender-bending, mind-altering, color-crazy, history-twisting looks, gowns, shoes, bodysuits, and haute handwork reminds us that JPG has been pushing the boundaries for over 40 years, inspired by French sailors, French culture, 50s TV, global culture, his grandmothers unmentionables drawer, and the ever-inspiring gritty street. How do you use embroidery, neoprene, stuffed silk tubes, tulle, and illusion in a subversive manner? Take a stroll through JPG’s master class.

You’ll find mermaids worn by Beyoncé, a French sailor-striped gown worn by Princess Caroline, red carpet looks worn by Ms. Cotillard, a Mongolian shearing coat sported by Bjork, and photos of supermodels and superstars sporting outrageous and inventive looks. The names of the collections alone tell you the scope of his interests – Haute Couture Salon Atmosphere, Ze Parisienne, Flower Power and Skinheads, Paris and Its Muses, So British, Forbidden Gaultier, and Great Journey collections.

Close-up of corset from JPG’s Countryside Babes collection, prêt-à-porter spring/summer 2006. Made of wheat and braided straw, created in 84 hours

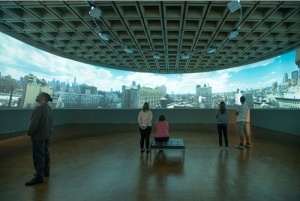

The show features 140 ensembles in all, enough to fill the entire wing. Mr. Gaultier even tells us that he expanded it a little for Brooklyn’s gigantic space, adding a “Muses” section with American icons and runway looks for big-boned, curvy girls.

Oh, and did I mention that the mannequins talk? (We can’t even begin on that, so here’s a video to explain how that magic happened.)

Brooklyn is the last stop on JPG’s North American tour, which was organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and Maison Jean Paul Gaultier.

If you can’t visit, take a walk through the show via our Flickr photos, and listen in on an hour-long discussion between JPG himself and the show’s curator Thierry-Maxime Lorio, where they talk about his “express yourself” philosophy.

The special promo video will give you a taste of the creative genius behind 40 years of memorable, challenging fashion as art: