Most fossil fans are familiar with the spectacular Jurassic marine reptiles found by Mary Anning along England’s Dorset Coast in the early 1800s, but few are aware that their predecessors – gigantic Triassic ichthyosaurs (250-201 mya)– have been emerging from the central mountains of Nevada’s Great Basin for the last 125 years.

A beautiful exhibition – Deep Time: Sea Dragons in Nevada – shines a spotlight on these magnificent extinct creatures, brings them to life through life-size animations, and tells stories of scientific discoveries at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno through January 11, 2026.

The art museum reunites the state’s stunning Triassic marine reptiles from museum collections across North America, and couples this with an engaging walk through 200 years of paleo-art history starring these enigmatic Mesozoic “sea dragons.”

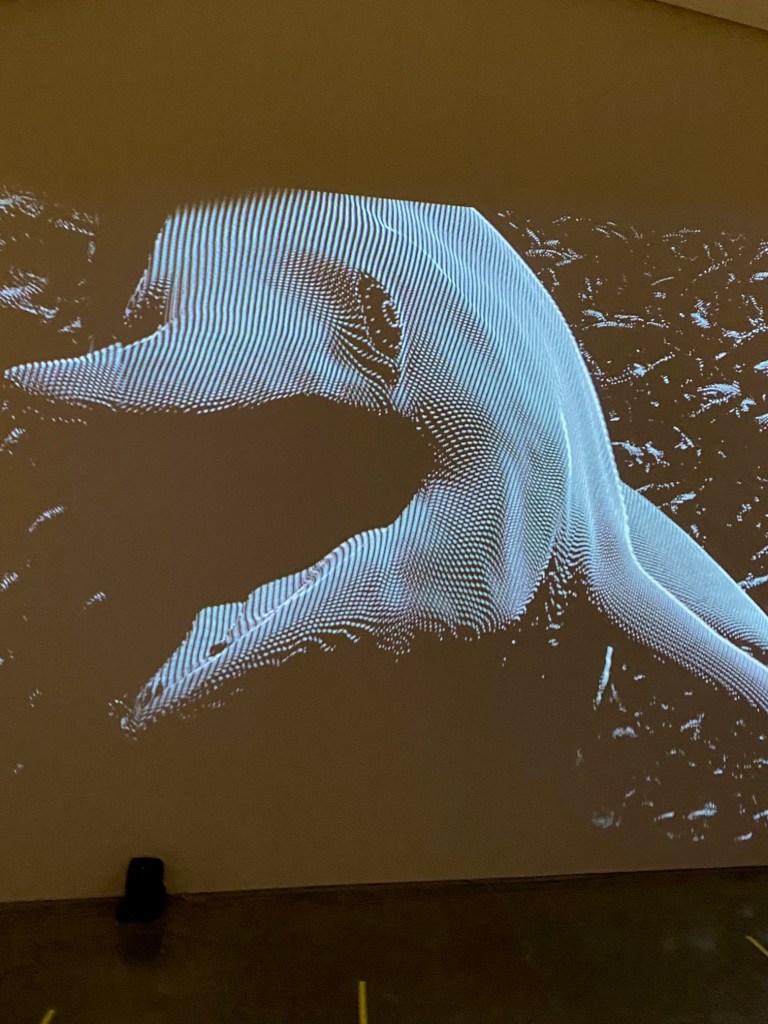

The most dramatic spectacle is on the far wall – a life-sized animated recreation of these gigantic swimming creatures by artist Ivan Cruz in collaboration with paleontologist Martin Sander and exhibition designer Nik Hafermaas. From the inky blackness, thousands of points of light emerge, float across the long wall, and coalesce into 3-D sea creatures that appear to swim across the entire length of the room.

Take a close-up look at the gorgeous Deep Time exhibition design and ichthyosaur animations by Hafermaas°creative here.

History, adventure, art, and expeditions intertwine. The gallery tells the story of ichythyosaur discoveries across three Nevada mountain ranges – the Humboldt, Shoshone, and Augusta. Each section presents spectacular ichthyosaur fossils and along with tales of intrepid paleontologists who have toiled away in Nevada’s most remote regions for over a century.

Nevada’s “sea dragon” story begins in the Humboldt Range in 1867-1868 as the U.S. Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, led by Charles King, discovers and collects bits and pieces of ichthyosaur ribs and vertebrae in their survey of the Great Basin. These discoveries spawned national news stories. The fossils ended up in Harvard’s museum collection, so it’s nice to see them here.

1905 was a big year for Triassic discoveries in the Humboldt Range. James Perrin Smith and his team from Stanford collected dozens of ammonites from the Humboldt slopes, and philanthropist Annie Alexander bankrolled (and participated in) John Merriam’s UC-Berkeley Saurian expedition.

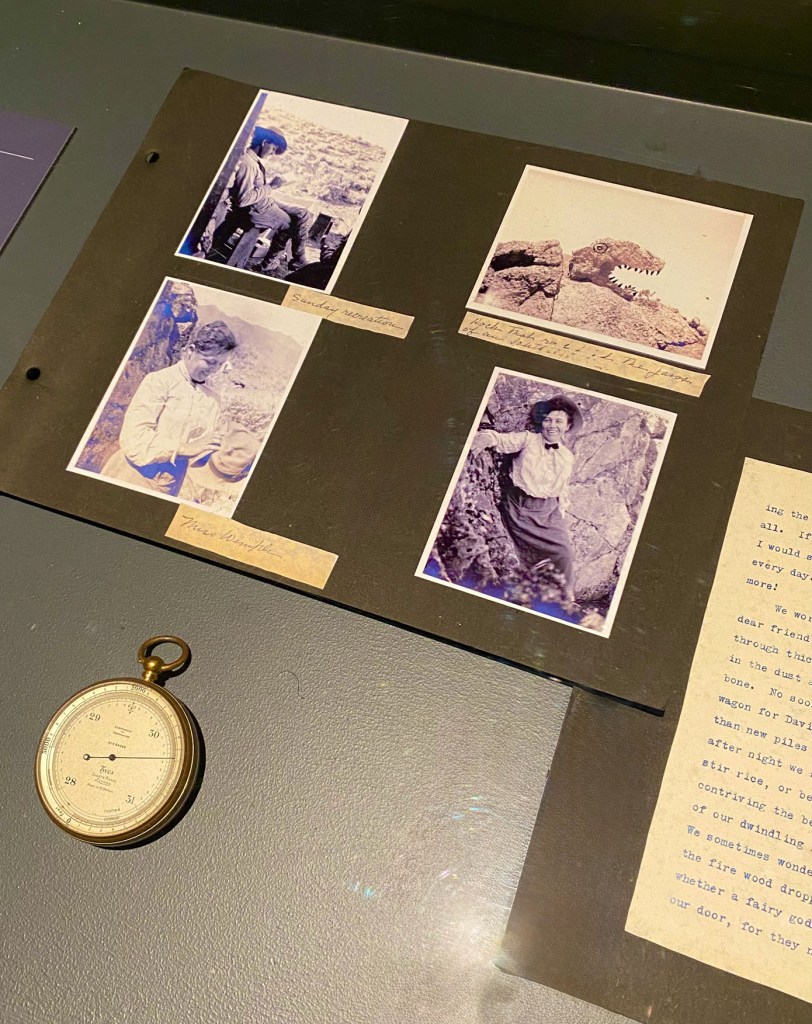

Merriam’s team excavated 25 ichythyosaur skeletons, loaded them out by horse-pulled wagons, and then got them back to Berkeley via train. Annie’s field notebook and photo scrapbook give us a look at the fossils, camp, and the team. In 1907, Annie founded and funded the UC-Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Her subsequent field trips led her to collecting more than Triassic fossils, but Annie’s the one to thank for kicking off spectacular preservation efforts for Nevada’s marine-reptile riches.

And as most fossil hunters know, discoveries are often made inside the collections storage room. It’s nice to see one of Annie’s 1905 fossils redefined as a new ichythyosaur species in the 21st century by exhibition co-curator paleontologist Martin Sanders!

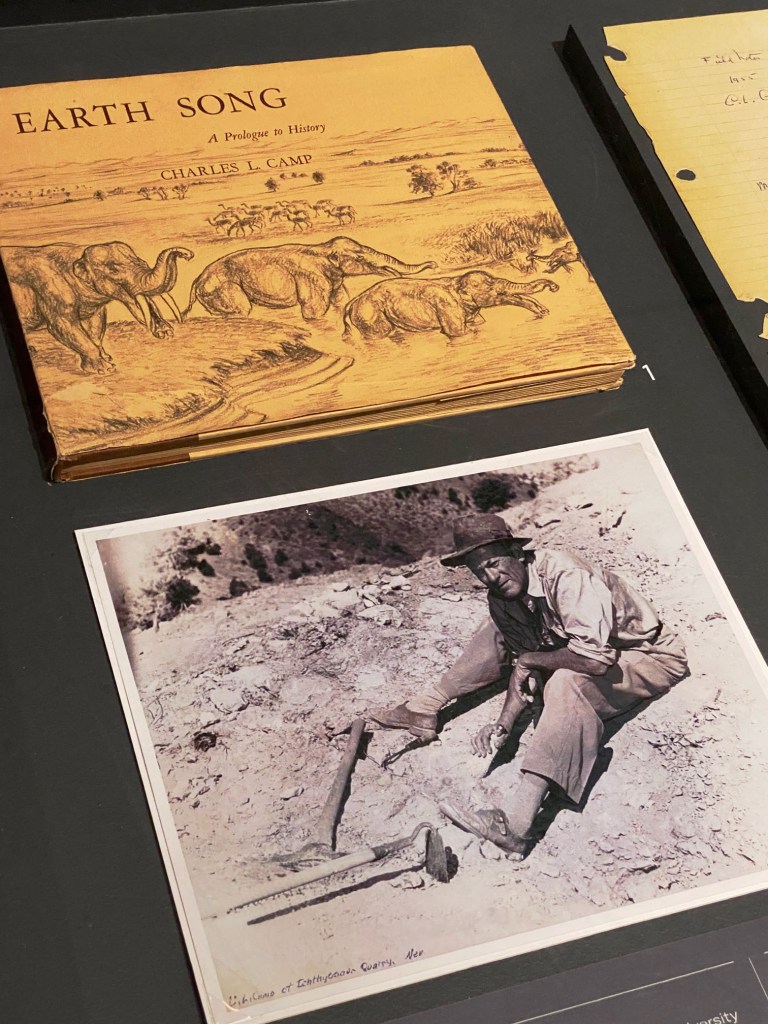

The story moves to the Shoshone Mountains near the old silver mining town of Berlin. In 1928, paleontologist Siemon Muller came across a massive amount of ichthyosaur remains encased in super-hard limestone near Berlin. Although he told the paleontologists at UC-Berkeley about them, no one followed up until Charles Camp went out to take a look in 1953. He found huge, articulated skeletons that were younger in age than the fossils from Humboldt.

Over the next ten years, Camp and his team found and sand-blasted out remains of 40 Triassic ichythyosaurs, which he later named Shonisaurus. In one quarry, the skeletons were so complete and numerous that Camp decided just to uncover their them and leave them exposed in place. People heard about these unique finds from news reports, and came out to marvel for themselves.

By 1957, the site was named a Nevada state park – a place where visitors could large concentrations of the world’s largest ichthyosaurs. Over time, Camp opened ten separate quarries in the area. The fossils Camp removed are now held in the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas.

For the last ten years, palentologists Randy Irmis and Neal Patrick Kelly have been working in the same area. The exhibition includes their recent ichthyosaur discoveries, including baby Shonisaurus bones, teeth, and a snount containing tooth sockets – evidence that the animal was likely a formidable predator.

Watch their video here for a history of ichthyosaur collecting in Nevada, a digital model of Camp’s main quarry, and new fossils

The Augusta Mountains has been the site of field work by Martin Sanders and team for nearly 30 years – – old and new ichthyosaur species, which are on display.

The exhibition includes a whimsical corridor leading to images from 19th-century paleo art and to vintage toys from a dinosaur and prehistoric-animal collector. The final room is a kaleidoscope of nostalgia – images from Europe’s earliest prehistoric ecosystem recreations to dinosaur collectibles from Chicago’s 1934 Century of Progress Fair.

It’s a fun way to observe how scientific thinking has changed about prehistoric marine lifestyles and body plans. Remember when science thought Brontosaurus spent its life submerged in lagoons? Or ichthyosaurs used their flippers to paddle around on land?

Take a look at our favorite fossils and toys in our Flickr album.

To see how art and science were brought together to create this immersive time-travel experience, watch this short documentary from PBS Reno, take a trip to Nevada’s Augusta Mountains with paleontologist Martin Sander and see how artists and designers brought his Triassic creatures to life:

It is an amazing exhibit. Informative and impressive with fossils on display and the stories of the early and recent paleontologists.

I had heard about the Berlin site but did not know about the amount and quality of fossils found there. It is on my ‘To Go’ list.

Great article MsSusanB. And it was fun to tour the exhibit with you!

MsLisaB 😉

Thanks for spreading the joy about this great exhibit!! An unforgettable experience touring it with you!

could this be Nessy and all the other strange lake creatures spotted??