It’s been just over 100 years ago that Juan Pino of Tesuque Pueblo popped into the Santa Fe studio of Charles Kassler, and experienced his enthusiasm about linoleum printmaking – a new-ish way to make multiple images without using an expensive press or chemicals.

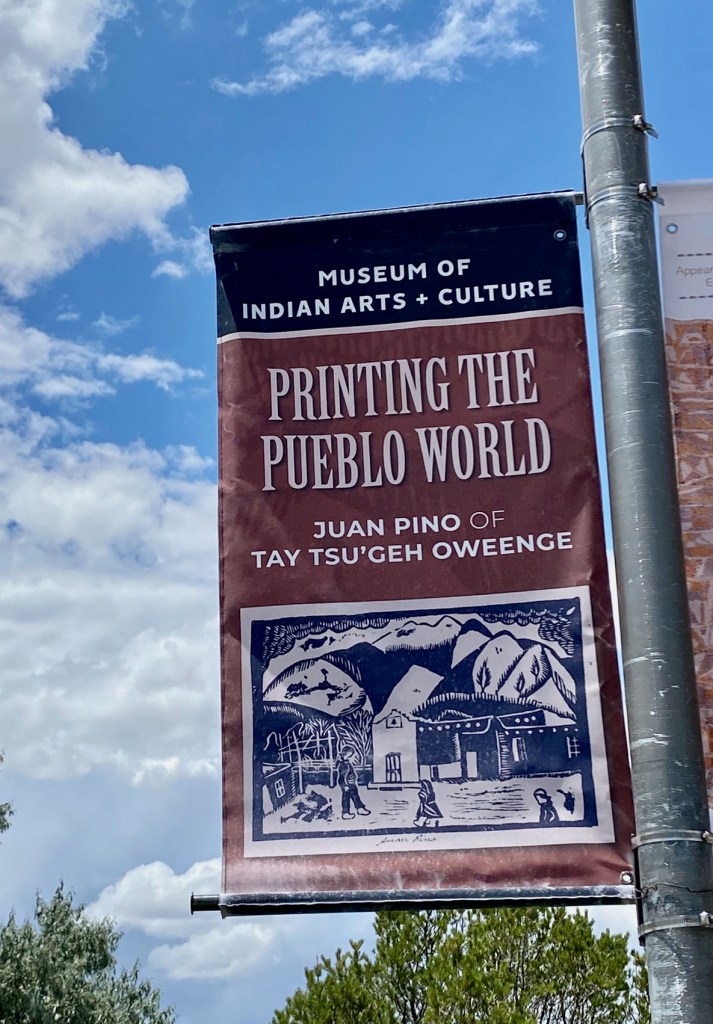

Charles offered Juan some materials to take home so he could try it, and Juan got to work. See the results in Printing the Pueblo World: Juan Pino of Tay Tsu’geh Oweenge, on display at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts and Culture through August 17, 2025.

Take a look at our favorites in our Flickr album.

Unlike his friend Kassler, who trained formally at Princeton and the Art Institute of Chicago, Juan received his artistic training in the Pueblo world, learning observation, craftsmanship, and patience from the ceramic and textile artists around him. By 1924, booming tourism in Northern New Mexico had created a big market for modern and traditional pueblo ceramics (think Maria Martinez and Margaret Tafoya) and for pueblo painters, like Julian Martinez and Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal).

Juan was an expert in wood carving, ceramics, textiles, and crafting dance regalia, but like most artists of his day, he juggled his artistic output with other income-generating pursuits – farming, gathering and selling home-heating wood, and posing as a model for Anglo artists flocking to the vibrant Santa Fe art colony.

For linocut printmaking, you just cut your design into linoleum – a relatively accessible material since it was manufactured for use in kitchen floors or wall coverings for new homes. Once the block was carved and inked, you could either apply manual pressure to make the multiple images or ask a fellow artist to borrow their press.

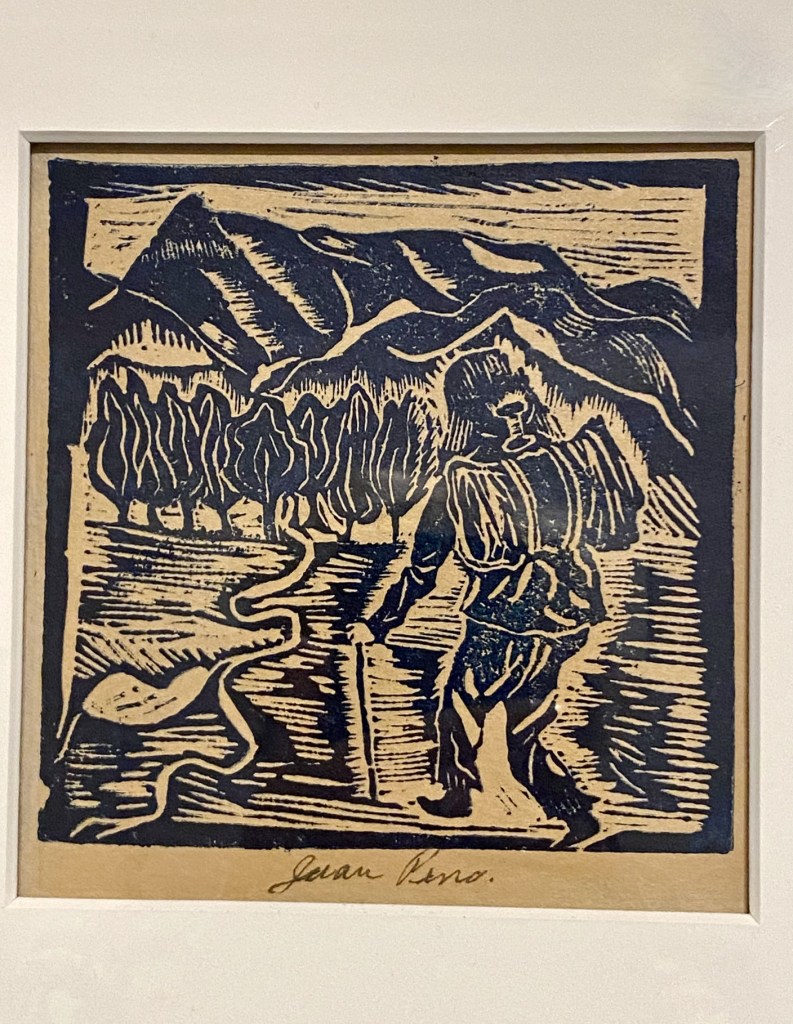

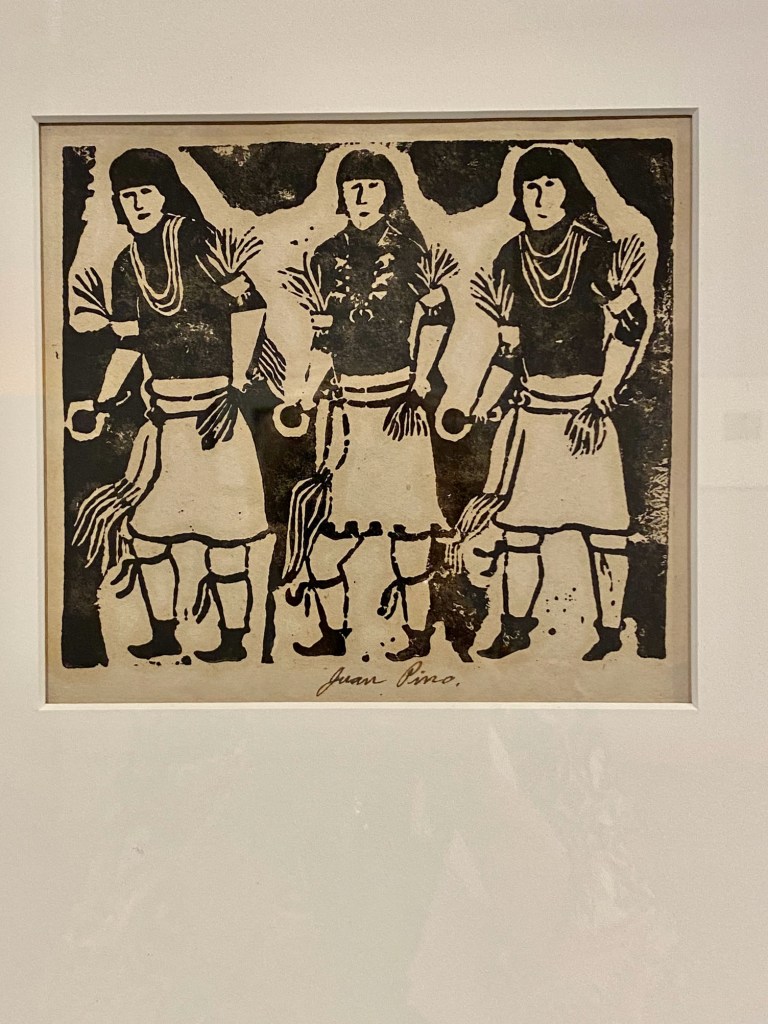

Carving images into linoleum came naturally, and Juan started depicting the world around him in Tesuque – not just romanticized images of Indian life. Juan carved and printed the daily comings and goings of his fellow villagers in the pueblo plaza and images of traditional dances.

For all the car traffic and hubub on the streets of Santa Fe during the 1920s, Tesuque pueblo life still had elements of traditional Tewa ways. Archaeologists have found remnants of village buildings dating back to 1200 CE, so Tesuque is one of the longest inhabited communities in the United States.

Taking in the twenty prints in the exhibition allows us to see day-to-day life as it was 100 years ago in the historic pueblo – making ceramics at home, harvesting, using oxen on the farm at a time just before horses replaced them as the work animal of choice. We can even see detailed black-and-white depictions of the regalia men were wearing for the Corn Dance – including one print that likely includes a self-portrait!

After only a few months of making linoprints in 1925, Juan’s work was displayed at the New Mexico Museum of Art. Santa Fe and Pueblo artists celebrated his accomplishment as the first Pueblo artist to try his hand at printmaking. In Santa Fe’s commercial gallery market, however, tourists were more inclined to purchase prints and paintings that showed more romanticized visions of Indian life.

Juan kept creating, and seeing so much of his work 100 years later is truly a revelation – a set of quiet, enjoyable glimpses of everyday life at the foot of the Sangre de Christo Mountains.

The show also has a beautiful touch that emphasizies Juan’s continuing artistic output: two large ceramic pieces from the Thirties and Forties created by his wife, Lorencita Pino. It’s likely Juan used his steady hand to apply strong, black lines – skills so evident in his masterful design for his slice-of-life print series.