Right inside the exhibit, Whales: Giants of the Deep, the American Museum of Natural History answers two questions that have stumped centuries of nature lovers – how did the world’s largest sea-loving mammals ever evolve from land animals, and who are their closest relatives?

In the last 20 years, DNA experts and paleontologists have been hacking away at these questions, and the show provides some startling visuals and answers: Whales (a group that includes dolphins and porpoises) came from four-legged animals that hovered close to shore lines, snapping up fish. Oh, and their closest relatives on the Mammal Tree of Life are…get ready…hippos. See the show before January 5.

Clue to solving the mystery – the skull of Andrewsarchus, three feet long, found in 1923 by Kan Chuen Pao on AMNH’s second Gobi expedition. Courtesy: AMNH/R. Mickens

The first thing you’ll see is a massive skull of Andrewsarchus, a 45-million-year-old whale cousin, who would have stood over six feet tall at the shoulder. He was found in Mongolia on the famous AMNH Central Asiatic Expedition in the 1920s (remember the dinosaur eggs?) and to this day is the only one found.

The paleo team compared the features on his skull to other mammals, ran their analysis through cladistics software, generated a family tree, and learned that Andrewsarchus falls somewhere near the evolutionary point where whales and hippos had a common ancestor, a key clue.

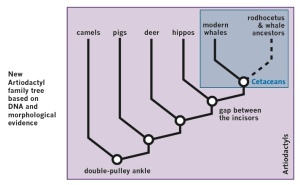

A huge discovery in Northern Pakistan in 1983 began to unlock the rest of the mystery. Found in 50-million-year-old Eocene rocks, remains of the enigmatic, four-legged, fish-eating Pakicetus were discovered at the edge of what was once an ancient sea. It was deemed by scientists to be the earliest known modern-whale ancestor. Many specimens were unearthed, with ear bones looking like modern-day dolphins, but ankle bones more like a pig’s, giving scientists a reason to place his ancestry in the “artiodactyl” category, which includes hippos, pigs, antelopes, camels, and other even-toed hoofed animals. Subsequent finds and DNA analysis of modern whales further solidified the hippo-relation hypothesis.

Cladogram showing family relationships of whales and artiodactyls from the AMNH guide for students in grades 6-8

The show includes a full replica of his skeleton, along with other fossils from the subcontinent showing the transition of four-legged wolf-sized animals to the streamlined bodies that we now associate with ocean- and river-going cetaceans. You’ll see a terrific video that animates the transition from longer-snouted, web-footed fish-eaters that paddled through estuaries (Ambulocetus), to more streamlined sea-going mammals whose front legs became flippers and back legs disappeared nearly completely. Kutchicetus (43-46 million years ago) shows evidence that it probably did some deep dives, and Durudon (37 mya) had nostrils at the top of his head, flipper-hands, and apparatus at the end of his tail that suggests a support for flukes.

The show was originally organized by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and features a mix of AMNH and Te Papa artifacts and insights.

There are many other wonderful biological, historical, and cultural details to the whale story, as the YouTube below shows (84K hits and counting), but shout-outs must be given to the two stars — large Sperm whale skeletons (think Moby Dick) on display, lovingly named and transported here by the Maoris, who found the stranded duo, prepared, and blessed them for special appearance in New York.

Reblogged this on High on Science & Tech – H.O.S.T.

Looks like a great exhibit. I wish I could be in town to see it.

But then you’ve got your own beautiful whales!

Looks like a fascinating exhibit and show Susan. Wish I could get there. I’m working on a similar progression trying to show the evolution of the Minnesota Yeti to Minnesota Viking Fan which we believe was a retro descendent of the Wisconsin Timber Ranger.

And you know that you have the skills to do it!